Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. This article was written by Salome Dolidze and Zachary Fabos, researchers at CRRC Georgia. The views expressed in the article are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of UN Women, CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

According to a new UN Women survey, although many Georgians believe both men and women are largely free to make decisions regarding their future, this does not extend to one’s choices around sex.

The majority of Georgians believe they have a high degree of control over their lives, the March survey has found. This extends to choices regarding one’s education, making financial decisions, finding employment, and when and with whom to marry.

However, according to the same survey, such freedoms do not extend to choices involving sex before marriage or having more than one sexual partner in one’s lifetime, especially when asked in relation to women.

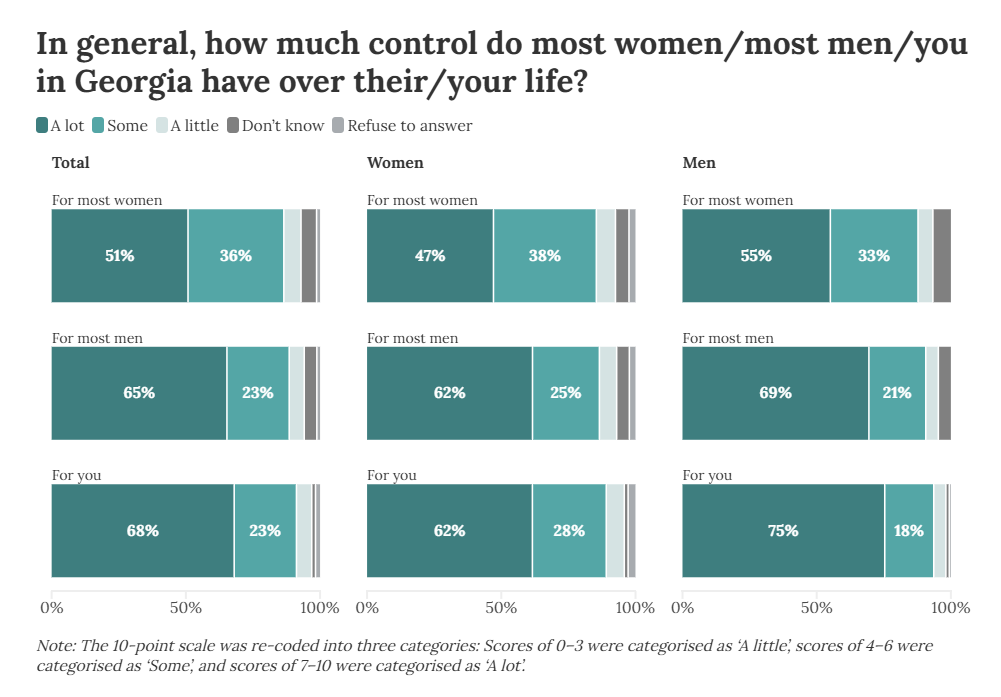

Georgian men and women were asked to indicate how much control they believe to have over their own life and how much control others have over theirs. Generally, men and women alike, granted themselves a higher degree of control than others, with 68% of respondents indicating they have a lot of control over their own life. Even so, men are still believed to have more control, with 65% of respondents stating that most men have a lot of control over their lives compared to 51% believing the same for most women. Interestingly, men are more likely to say that they have a lot of control over their lives compared to women.

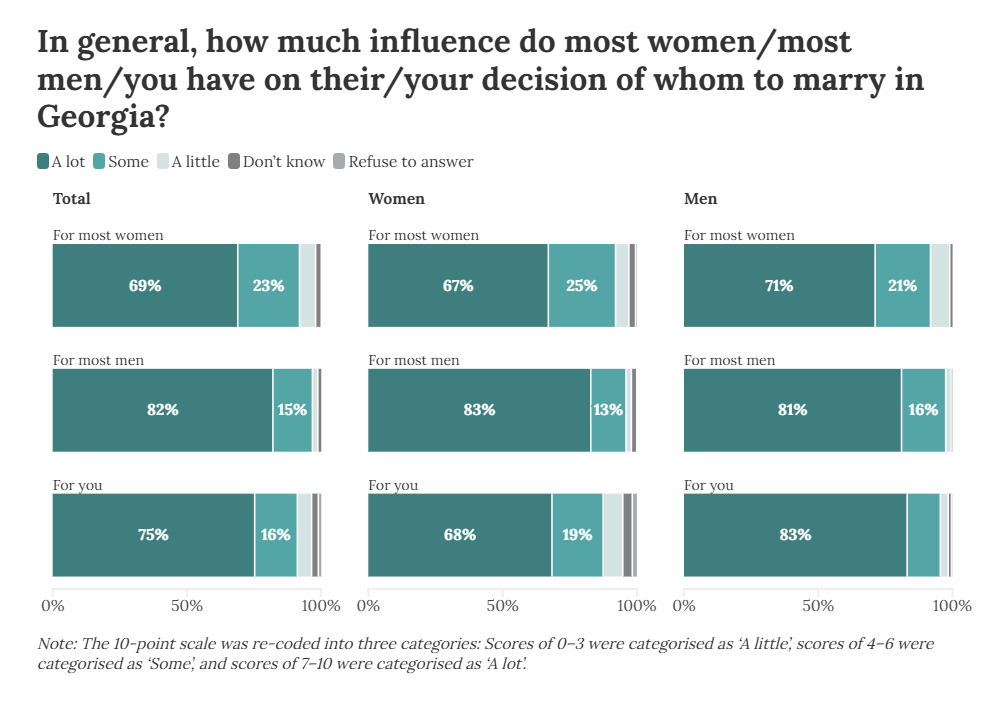

Georgians felt similarly when asked about the freedom to choose whom they marry — overall, 75% claimed to have a lot of influence in choosing whom they marry.

Again, Georgians agreed that most men have more influence in this choice than most women. However, a majority (69%) still believed most women have a lot of influence in deciding whom to marry.

Broken down by gender, 68% of women believed they have a lot of influence in deciding whom to marry, compared to 83% of men.

Opinion differed among Georgians when asked about choices regarding sex before marriage and having more than one sexual partner in one’s lifetime.

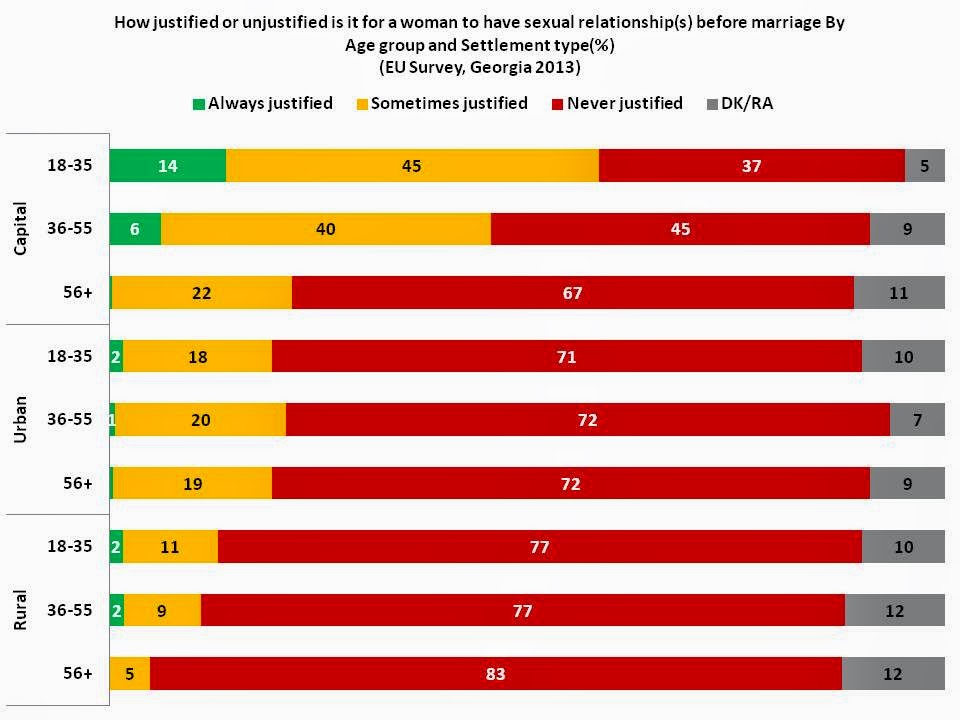

When asked if it was justifiable for people to have a sexual relationship before marriage and to have several sexual partners in one’s lifetime, Georgians generally stated that it was somewhat more justifiable for men to do so compared to women. A slight majority (51%) of Georgians believed it was justifiable for men to have a sexual relationship before marriage, compared to 30% believing the same for women. Although most Georgians believed it was unjustifiable for both men and women to have several sexual partners in their lifetime, it was perceived as more justifiable for men by 12 percentage points, compared to women.

In addition, individuals 35 and older, those living outside Tbilisi, and those who had higher education were more likely to say that it was not at all justifiable for women to have sexual relationships before marriage than younger people, residents of Tbilisi, and ethnic Georgians.

Likewise, people living outside Tbilisi and those aged 55 and over were more likely to say that it was not at all justifiable for women to have several sexual partners in their lifetime than people living in the capital and younger people.

The results of the UN Women survey demonstrate a clear disassociation between personal freedoms and sexual autonomy among Georgians. Although many Georgians believe men and women are free to make decisions regarding their relationships, finances, and futures, such liberties do not extend to one’s choices around sex.

The regression analysis used in this article included the following variables: age (16–24, 25–34, 35–54, 55+); Sex (male or female); settlement type (Tbilisi, other urban, rural); education level (Secondary or lower, vocational, tertiary); ethnicity (Ethnic Georgian or ethnic minority); and employment status (employed or not working). The data used in the article is available here.