On June 28, 2013 the Georgian parliament passed a law placing a moratorium on agricultural land sales to foreigners until the end of December 2014. Agriculture has been called one of the pillars of the Georgian economy as 53% of Georgians were employed in agriculture in 2011 according to a European Union Neighborhood Programme report. Furthermore, agricultural investment has been the focus of both the current Georgian Dream coalition government, as well as the previously governing United National Movement. As a blog by the International School of Economics at Tbilisi State University highlights, the question then becomes, if Georgia wants to invest in agriculture, where will the money come from if not abroad? This blog looks at how Georgians feel about doing business with different ethnic groups as well as how Georgians feel about Georgian women marrying outside their ethnic group. The post also considers knowledge of foreign languages in rural areas in order to highlight that communication between Georgian and foreign farmers would be difficult without a common language.

Approximately 2,000 Indian farmers settled in Georgia according to a 2013 BBC report. This led to the incitement of protests particularly in the eastern Georgian province of Kakheti in 2013. The 2010 Caucasus Barometer asked Georgians how they felt about doing business with Indians. Results of the survey showed that 64% of rural Georgians approved of doing business with Indians compared to 71% of Georgians in Tbilisi. By looking at how Georgians living in rural areas feel about doing business with other ethnic groups, we can see how the Georgians most likely to be involved in agricultural activity might be inclined to working with foreign agricultural investors. The following graph shows that doing business with Iranians, a group that has also been reported to be investing in agricultural land in Georgia, is approved of by 59% in rural areas, compared to 86% in Tbilisi.

A further way of gauging how rural Georgians feel about foreigners is looking to whether they approve of Georgian women marrying other ethnic groups. Though Georgians generally are against marriage to foreigners, rural residents consistently disapprove of Georgians marrying other ethnic groups more often than Tbilisi based Georgians. The following graph shows this relationship for Russians, the ethnic group which Georgians are most likely to approve of Georgian women marrying. Notably, rural Georgians approve 15% less than Tbilisians. This question may be related to rural support of the moratorium. Although the CB 2013 does not ask whether respondents would like to have foreign neighbors, presumably rural inhabitants would be less likely to want foreign neighbors if they are unlikely to support the marriage of a local woman to a foreigner.

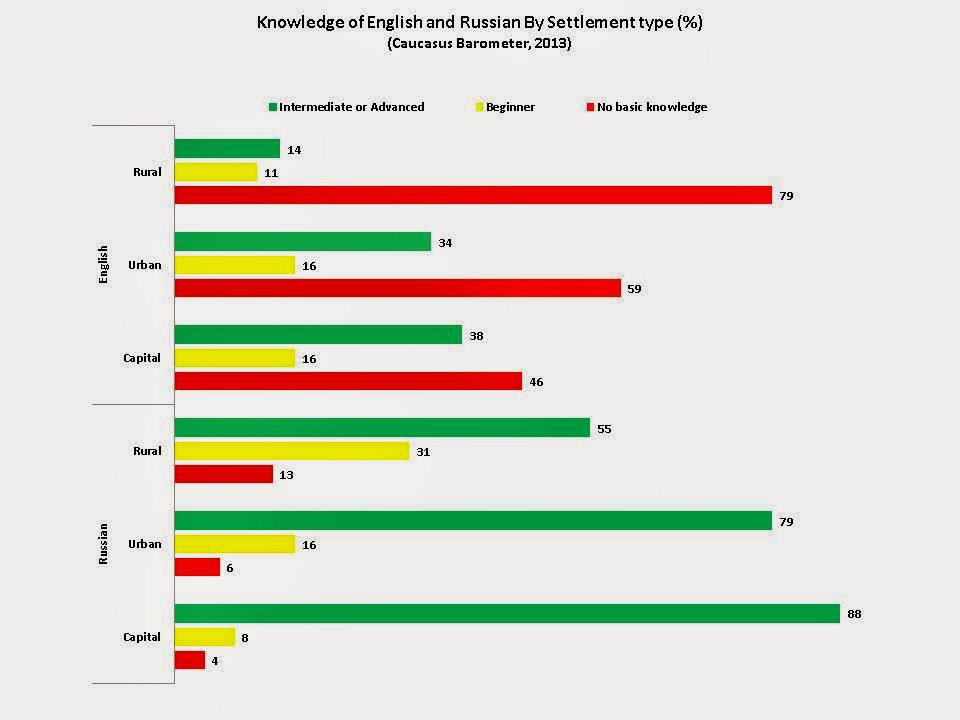

An additional factor to consider is that rural residents are much less likely to speak a foreign language compared to urban or capital based residents. The majority of rural Georgians (80%) report having no basic knowledge of English compared to 46% of Tbilisi’s residents reporting no basic knowledge of English. Furthermore, 44% of rural residents report having either no basic knowledge or a beginner’s level of Russian, compared to 12% of Tbilisi residents who say the same.

Note: Responses of Intermediate and Advanced were combined in this graph.

With the language barrier, it could be difficult for Georgian and foreign farmers to form relationships and communicate effectively. In order to avoid the language barrier, a number of companies have brought their own labor force to the country, including the Xinjiang Hualing Group which operates a small factory town on the outskirts of Kutaisi. Despite this, many foreign farmers who have moved to Georgia report hiring Georgians, especially during the harvest season. This could be a further factor which has conditioned the relationships existing between local and foreign farmers, as well as future relations between them.

This blog post has looked at the perspectives of rural residents on doing business with members of other ethnic groups as well as their level of knowledge of English and Russian. It shows that rural Georgians are much less likely to approve of doing business with other ethnicities, and that rural residents are much less likely to have knowledge of Russian or English. With these factors in mind, support for the ban on agricultural land sales may be more understandable. If residents in rural areas, many of whom are involved in agriculture, are less likely to be able to communicate with foreigners and are more likely than other Georgians to disapprove of relationships with them, then would they want them as neighbors? To explore these issues further, we recommend using our ODA tool here or reading this blog post detailing the extent of foreign agricultural holdings posted on the Transparency International Georgia website.