Calling 2014 turbulent for the world seems almost euphemistic. The world witnessed renewed Russian revanchism with the war in Ukraine and annexation of Crimea, the emergence of a highly successful militant Islamic organization, Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, and the persistently tense situation in Israel erupted into another war between Israelis and Palestinians. Not only did the world see conflict, but it also witnessed the outbreak of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and electoral gains for the far right and left in Europe. Notably, Turkey continued on its path which has swung against secularism and democracy in recent years.

In contrast, Georgia, a country known for its prolonged territorial conflicts and volatile politics, was relatively calm in 2014. This, though, is not to say that the events which shook the world in 2014 did not reverberate through Georgia. Quite to the contrary, the Ukraine crisis resonated in Georgia and the conflict in Syria holds consequences for the country. Georgia’s domestic politics, while tame in comparison to the recent past, also had unexpected and difficult moments.

The crisis in Ukraine reminded the Georgian public of the threat posed by Russia, and for many it was also a reminder of what could have happened in 2008. As a CRRC blog post pointed out in September, Georgians’ perception of Russia as a threat increased during the crisis. Moreover, the crisis in Ukraine hastened the signing of Georgia’s long sought after Association Agreement with the European Union. While the Agreement was originally scheduled to be signed no later than August 2014, after the Ukraine Crisis, the European Union moved up its signing to no later than June 2014, ultimately culminating in the signing on June 27th.

One of the most unexpected outcomes of the Ukraine crisis is the proposed appointments of a number of former Georgian United National Movement officials to the Ukrainian Cabinet of Ministers. Former Minister of Health and Social Affairs of Georgia, Aleksandre Kvitashvili, and former deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, Eka Zguladze, have taken up the same posts in the Ukrainian government. Notably, ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili turned down the Vice Premiership of Ukraine to keep his Georgian citizenship. While the proposed appointments have not been received with absolute unanimity from the governing Georgian Dream Coalition, Foreign Minister Tamar Beruchashvili has noted the importance of maintaining good relations with Ukraine.

The Ukraine crisis was not the only global event to reverberate in Georgia in 2014. The war in Syria and Iraq, which has resulted in massive loss of human life and mass displacement, also touched Georgia. After the start of the conflict, Georgia’s previously ultra-liberal visa regime made it relatively easy for Syrians to settle in the country. Notably, some ethnic Abkhaz Syrians fled to Abkhazia from the conflict. This year though, a number of young people from the Pankisi Gorge in northeastern Georgia have joined the war in Syria and Iraq, becoming not only members, but also high level commanders of the militant Islamic organization, Islamic State.

On a different note, Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration took another step forward this year with agreement on a “Substantive Package” with NATO. This package was given to Georgia to increase interoperability with NATO countries, while also serving as a substitution for a Membership Action Plan which in the context of the Ukraine crisis and the unsettled conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, may have provoked Russia’s ire.

In what some commentators have viewed as a response to NATO’s substantive package, Abkhazia and Russia signed a treaty, including a mutual defense clause similar to Article 5 of NATO’s Washington Treaty. Both Abkhazians and Georgians have heavily criticized the treaty. The Georgian government has described this treaty as a further step in Russia’s occupation of Abkhazia, and Abkhazians have criticized the treaty for giving up too much autonomy. While the first draft of the treaty was titled “Agreement on Alliance and Integration” it was later changed to “Agreement on Alliance and Strategic Partnership” (emphasis added) as a result of Abkhaz protests. Significantly, the Kremlin-favored candidate Raul Khajimba was elected to the de-facto presidency of Abkhazia, following a June revolution in the breakaway republic.

Speaking of entirely domestic events, in 2014, intolerance again manifested itself in Georgia with a number of islamophobic and homophobic events. The most extreme example of islamophobia this year was when residents of Kobuleti decapitated a pig and nailed its head to the front door of a Muslim boarding school in protest of the schools opening. On May 17th, the physical violence of 2013 protests against the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia was avoided since the anti-homophobia rally was cancelled due to the fear of repeated violence. Instead, the Georgian Orthodox Church along with its supporters celebrated a “day of family values” on May 17th, a clear act of symbolic violence.

The political scene was also somewhat turbulent. The Georgian Dream Coalition experienced its first serious crack with the dismissal of Irakli Alasania from the Defense Minister post in November and the subsequent withdrawal of the Free Democrats from the coalition. Notably, the public’s appraisal of the Georgian Dream Coalition’s performance has decreased in 2014. While in November 2013 50% of the population rated their performance as good or very good, only 23% of the population reported the same in August 2014. The municipal elections in 2014, which demonstrated a high level of competition compared to many elections in the past, also held a number of surprises. Importantly, the newly emerged Patriotic Alliance garnered nearly 5% of the vote nationally and forced a second round in gamgebeli elections in Lanchkhuti.

Elections and coalition politics aside, an event in Georgia which remains unsettled to this day is the charging of Mikheil Saakashvili with a number of crimes he allegedly committed while in office. Saakashvili has denied any wrong doing and accused the current government of a political witch hunt. The government has claimed that they are attempting to demonstrate that everyone is equal before the law and that justice, which was precarious during UNM rule, has returned to Georgia.

While the world shook in 2014, Georgia mainly felt the weaker aftershocks of world events in 2014, and although Georgia experienced crises in miniature, it has navigated domestic issues with a relative grace. Still, the crises in Ukraine and Syria left their mark on Georgia, and will continue to impact Georgia in 2015.

Monday, December 29, 2014

Georgia in a turbulent world: 2014 in review

Tuesday, October 01, 2013

Islam in Azerbaijan: A Sectarian Approach to Measuring Religiosity

Posted by

Unknown

at

4:44 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, Caucasus Barometer, God, Islam, Religion

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

Different Perceptions of God in the South Caucasus

Posted by

Unknown

at

10:12 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ARDA, God, Islam, Religion, South Caucasus

Thursday, December 06, 2012

The Modalities of Azerbaijan's Islamic Revival

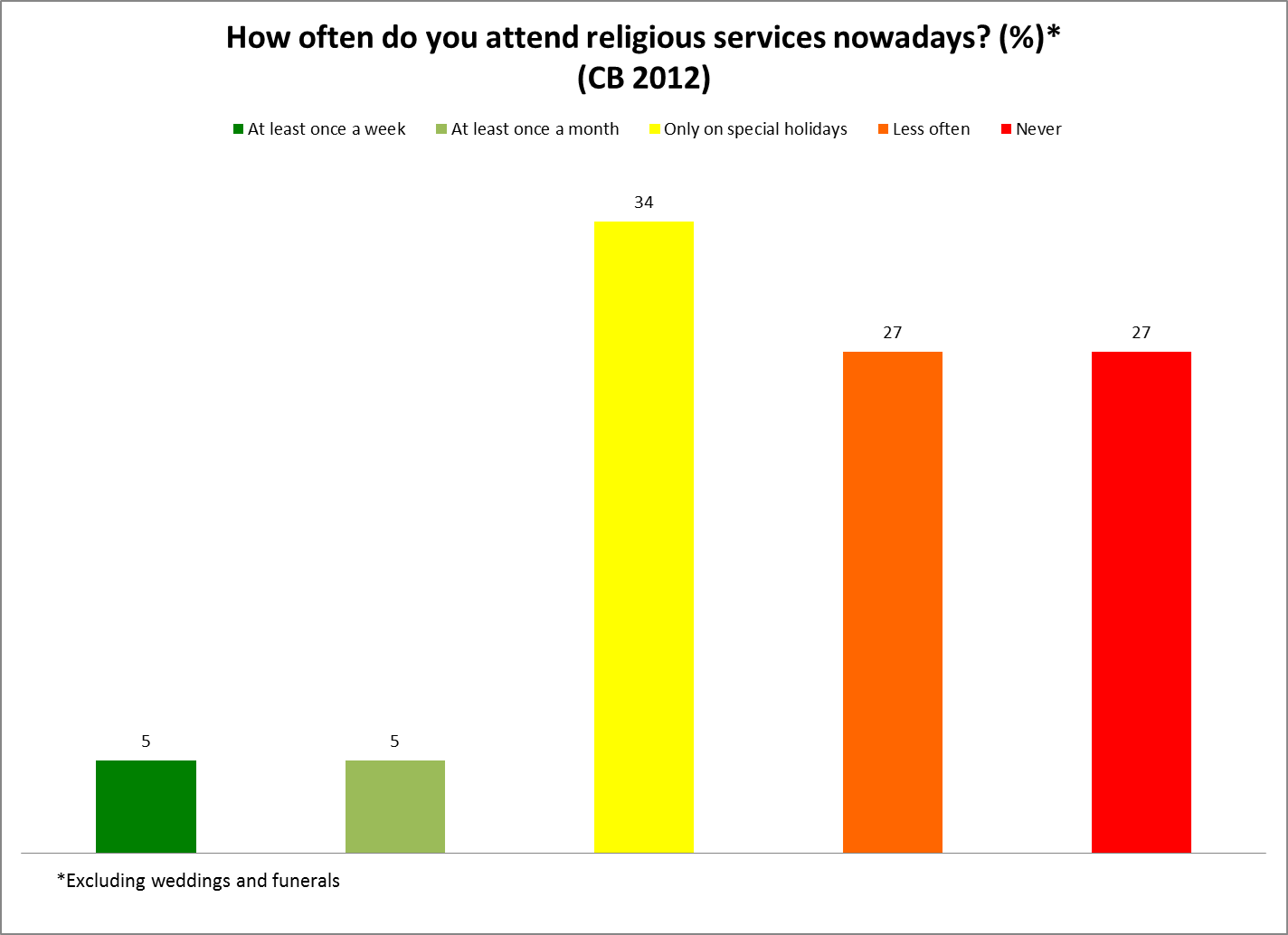

Yet, if Azerbaijani society is indeed experiencing an Islamic revival, what are the manifestations of its increasing religiosity? According to data from the Caucasus Barometer (CB) and CRRC's 2012 Social Capital, Media and Gender Survey (SIDA), religious indicators such as overt religious practices and trust in religious institutions have actually shown negative trends in the last five years. Nevertheless, other indicators suggest that Azerbaijanis' private religious practices and conceptions of personal religiosity may be gaining greater currency.

According to the CB 2008, 10% of people in Azerbaijan claimed to attend religious services on at least a weekly basis, while 7% and 36% attended at least once a month or on special holidays, respectively. Around 20% of Azerbaijanis attended services "less often" and nearly 30% "never" attended.

Posted by

Unknown

at

1:25 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, Institutions, Islam, Religion, Trust

Monday, April 20, 2009

PhD thesis: What are the Motives for Islamic Activism in Azerbaijan?

(a) The younger generations wish to break ties with Soviet institutional structures, in particular those that are characterized by authoritative measures towards individual choice

(b) Discontent with societal development after Azerbaijan’s independence

Azerbaijan, considered as one of the least religious nations in the world, has since the end of the 1990’s experienced repressive state measures towards domestic Islamic movements. The pretext for state sanctioned clampdowns against the growing national opposition with distinguishable Islamic features required, according to decision makers, unorthodox countermeasures.

“By re-imposing strict state control over the religious practitioners and the religious organizations, the leadership in the independent republic hoped, just as their Soviet predecessors, to neutralize the oppositional potential in religion in order to avoid a development as in neighboring Iran. Some Moslem groups that questioned the religious structures got classified as oppositional and were actively opposed by the state”. Sofie Bedford

Friday prayers at the Abu Bakr mosque in Baku, Azerbaijan

Friday prayers at the Abu Bakr mosque in Baku, AzerbaijanBedford argues that a crucial component of the state repression that strengthened Islamists consisted of official negative propaganda on the Abu Bakr mosque as a “nest for violent wahabis” and the Juma communion as “radical Shiites planning an Islamic revolution”. Instead of ending the mobilization of the mosque attendees, the state’s counterstrategy back clashed and strengthened the affinity of the targeted groups as discontent with corrupt state policies thrived.

“Amongst the visitors, and many others, Juma and Abu Bakr came to symbolize an unafraid, creative and free Islam which gave renewed popularity and, consequently, increasing numbers of attendees. It is important to stress that even if there were many similarities between the mobilization processes in the Juma and Abu Bakr communions, the study shows interesting differences, in particular in their interaction with the state in the later stages of the mobilization processes”.

In order to access the full PhD dissertation, please follow this link. In addition to the dissertation, we would also like to recommend this shorter article titled “Islamic Revival in Azerbaijan” for our readers out there.

Posted by

Cemal Ozkan

at

10:42 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, Baku, Islam

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Public Opinion in Azerbaijan and the Islamic World

I attended an event on the release of a new study on public opinion in the Islamic world on terrorism, al Qaeda, and US policies. Although the research includes Azerbaijan, the study’s focus is the region in immediate proximity to Israel and Afghanistan. Most of the results of the poll are quite predictable. In general terms, the perception of US goals and policies are that they are driven by economic interests, a desire to spread Western values, democracy and Christianity.

- 66% think that the US having naval forces based in the Persian Gulf is a bad idea

- 65% think that the US seeks to weaken and divide the Islamic world

- 90% believe that it is a US goal to maintain control over the oil resources of the Middle East

- 47% think that the US is often disrespectful to the Islamic world, but out of ignorance and insensitivity

Interested in further information? Here is where you can access the full report and the questionnaire for the survey.

Posted by

Cemal Ozkan

at

7:23 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, Islam, Values

Friday, February 02, 2007

OSCE on Islamic and Ethnic Identities

The OSCE has recently released a new discussion paper entitled, "Islamic and Ethnic Identities in Azerbaijan: Emerging Trends and Tensions"(in PDF format).

In the paper, Hema Kotecha, aims to analyze sources of instability in Azerbaijan emanating from Islamic and ethnic groups. Overall, the report provides a decent overview of many of the main ethnic and Islamic identities now prevalent in Azerbaijan and gives some description of how they interact with the Azerbaijani state; the report does better with the ethnic identities than it does with the religious ones. However, the report aptly notes the difficult of disentangling these various identities and the author often struggles to succinctly summarize the relationships between the various groups.

The report also gives some interesting statistics. For instance, the author notes that in one survey, "83% of respondents considered the religious affiliation of a marriage partner to be important. Yet the total number of respondents who identified themselves as 'religious' (dine inananlar) and 'devout' (dindarlar) is lower, 78.3%, indicating that those who are simply 'respectful towards religion,' 'atheist,' or neither, religious identity is an important factor" (Kotecha 2007: 3). But the scholar fails to meet basic academic standards of documentation by not naming the survey from which these statistics came from or what kind of sample was involved when these data were collected.

Indeed, the report highlights the continued role of anecdotal evidence in research in Azerbaijan and raises the need for more comprehensive survey data. The paper also raises the problem of of interviewing local elites and claiming they represent the population as a whole. Local elites in places like Zaqatala or Khachmaz are certainly not the Baku intelligentsia, however, they may not represent people who do not take part at all in local politics or civil society.

The problems in both interviewing and quantitative data collection show the need of having researchers who invest in the long term. Most of the religious developments in Azerbaijan will not easily be understood by people who have not invested considerable time and resources--often years--and this kind of investment is rarely undertaken by outside consultants.

Posted by

AaronE

at

11:34 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, ethnic minorities, Islam