Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Anano Kipiani, a Policy Analyst at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

Immigration from Georgia is common, with a prime motivator being the difficult economic situation in the country. Indeed, about three-quarters of Georgians have a close relative living abroad, and most send remittances to their relatives in Georgia. In turn, remittances made up 12.9% of the country’s GDP in 2019. By comparison, agriculture’s contribution to GDP was about half of this number, at 6.5%.

The study compared households that receive remittances to: similar households without remittances; similar households with migrants but who do not receive remittances; and similar households without migrants.

Additionally, households that have migrants, but do not receive remittances were compared to the other three groups of households. This was done using a process called matching, which identifies similar groups of individuals.

Who gets remittances?

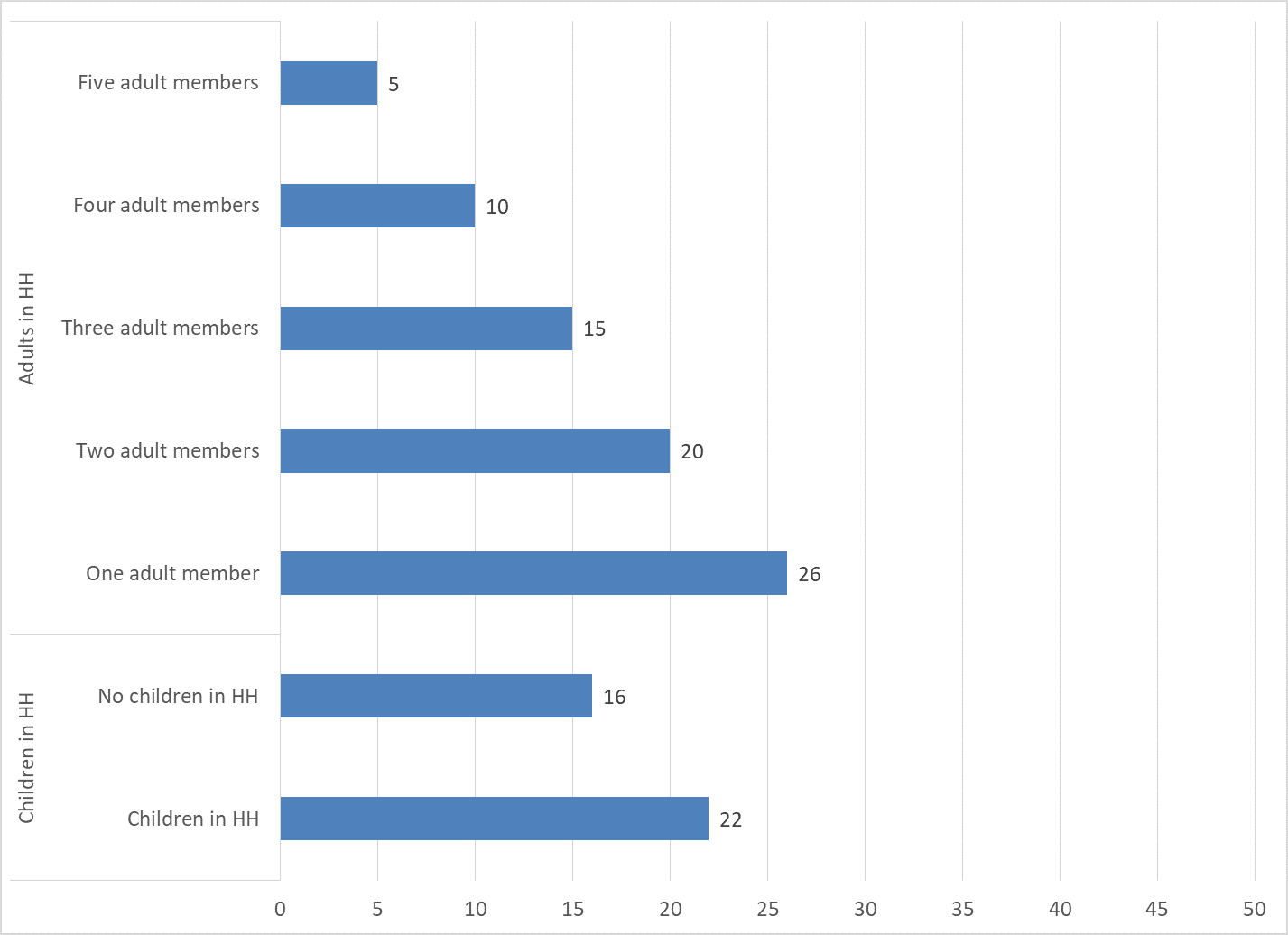

Overall, 19% of households reported receiving remittances from abroad in 2019. While looking at the types of households that receive remittances, a regression analysis suggests that households with one adult household member are 21 percentage points more likely to get remittances than households with five adult members. Households with children are six percentage points more likely to get remittances than households without children.

What are the impacts of remittances?

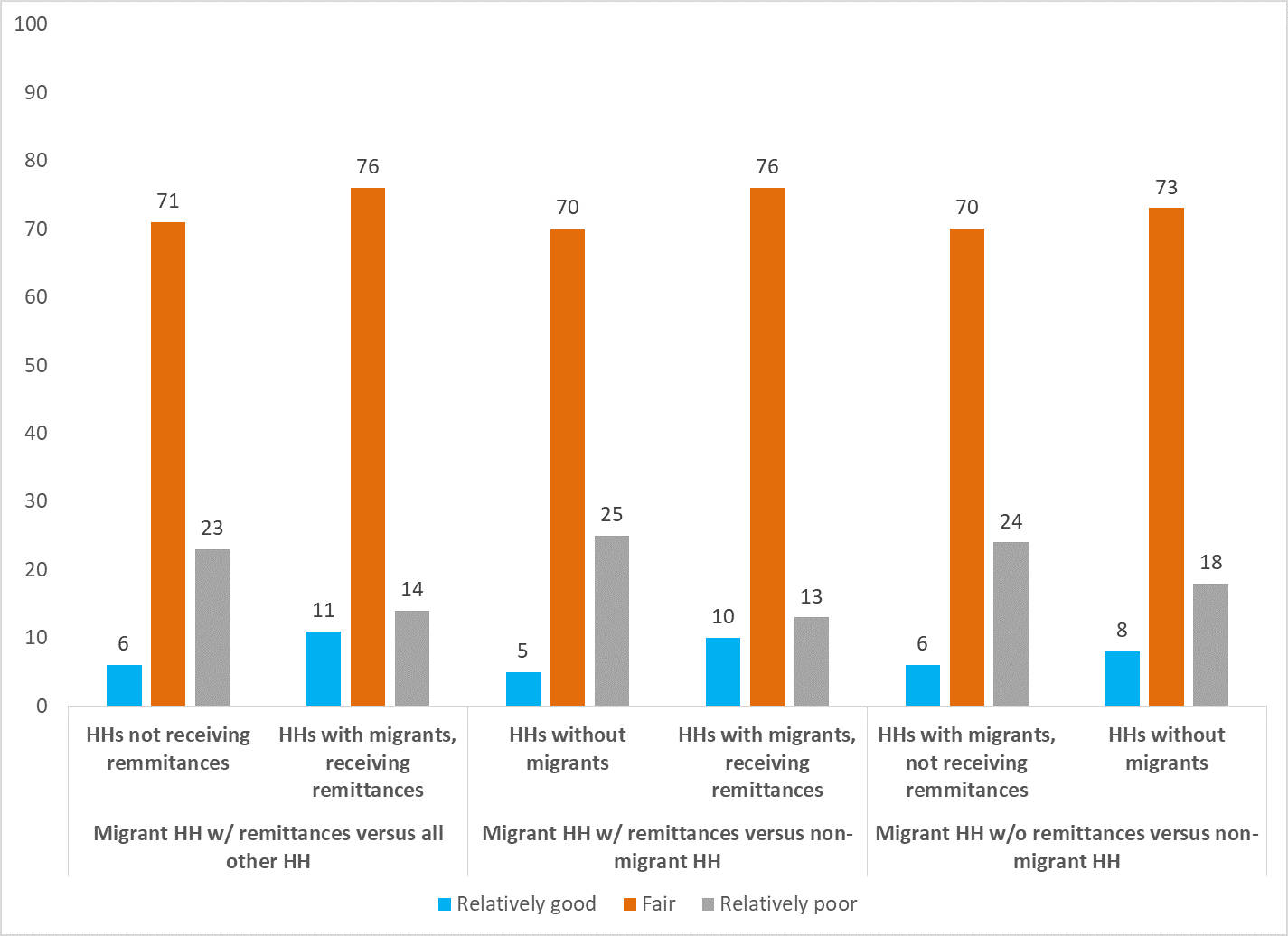

Households which receive remittances report their economic conditions are relatively positive compared to similar households that do not receive remittances. They are five percentage points more likely to assess their economic condition as relatively good, and nine percentage points less likely to believe they have relatively poor economic conditions.

In contrast, migrant households that do not receive remittances are slightly more likely to assess their economic condition negatively (by six percentage points) compared with households that do not have migrants.

Households that receive remittances compared with all other households were nine percentage points more likely to be able to afford enough food and clothes, five percentage points more likely to be able to afford to buy expensive durables, and eight percentage points less likely to not have enough money for food compared with other similar households.

Remittances also appear to be associated with higher monthly incomes. Households with remittances are seven percentage points slightly less likely to report they earn less than $100 a month compared with all other households and migrant households without remittances. However, households with remittances are slightly more likely to respond ‘don’t know’ or refuse to answer, which is often associated with higher levels of asset ownership and in turn, likely income, in Georgia.

Households that receive remittances also have more durable goods than others. From a list of 10 different goods asked about on the survey, migrant households owned nearly one additional good on average. At the same time, households with migrants that do not receive remittances had slightly fewer durable goods than households without migrants.

Overall, the data suggests that people benefit from receiving remittances, at least in economic terms. In contrast, households that have migrants but do not receive remittances do relatively poorly on some measures, though by no means all. Despite these positive economic impacts, the results do not speak to any effects, social, psychological, or otherwise, which may be tied to migration.

The data used in this post as well as replication code for the analysis is available here. A full policy brief on this issue is available here. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia.