Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dr. Tinatin Bandzeladze, a Researcher at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

Drugs have been slowly but surely finding their way into the everyday lives of Georgians for years now; in 2020 alone, CRRC Data suggested that drug users in Georgia, at a very minimum, spent $1.5 million on drugs through the dark web between February and August.

And yet, data from CRRC Georgia’s Caucasus Barometer suggests that drug users are still widely stigmatised in Georgia, creating a barrier to harm reduction and prevention programming and possibly standing in the way of reducing the harm of illicit drugs in Georgia through prevention-oriented policies.

Data from 2017, 2019, and 2021 Caucasus Barometer surveys suggest that the only group which people would least like to have as neighbours are criminals. Drug users take second place in the most recent wave of the survey, previously being tied in this position with homosexual people. In 2021, 27% of the public reported they would least like to have a drug user as a neighbour. This share has not changed significantly, with movement remaining within the margin of error since 2017.

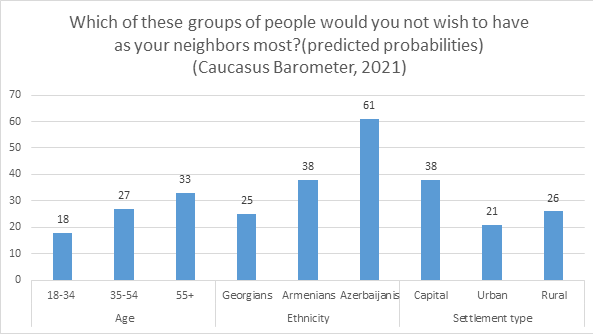

Whether or not a respondent named a drug user varied with age, ethnicity, and settlement type.

Controlling for other factors, people over 55 are 15 percentage points more likely than people aged 18-34 to mention drug users as unwanted neighbours.

Ethnic Azerbaijanis are 36 percentage points more likely than ethnic Georgians to name drug users as undesirable neighbours.

Settlement type is also associated with negative attitudes toward drug users. People in Tbilisi are 17 percentage points more likely than residents of other urban areas and 12 percentage points more likely than rural residents to rule out drug users from a list of potentially undesirable neighbours.

Employment, marital status, educational attainment, and religion are not associated with attitudes towards drug users in Georgia — at least not as measured by this variable.

The above data suggests that drug users are stigmatised in Georgia, with many implicitly preferring to have a criminal as a neighbour rather than a drug user. In turn, this suggests that the stigma drug users face may be a barrier to the effective implementation of harm reduction policies and programming in the country.

Note: The data used in the blog can be found on CRRC’s online data analysis tool. The analysis of which groups had different attitudes towards drug users was carried out using logistic regression. The regression included the following variables: sex (male, female), age group (18-35, 35-55, 55+), ethnic group (ethnic Georgian, ethnic Armenian and ethnic Azerbaijani), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), educational attainment (primary, secondary, technical or higher education), employment situation (working or not), marital status (married or single) and religion (Orthodox Church, other Christian groups, or Islam). The outcome variable was whether or not a respondent mentioned drug users.