Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dr. David Sichinava, Makhare Atchaidze, and Nino Zubashvili, CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

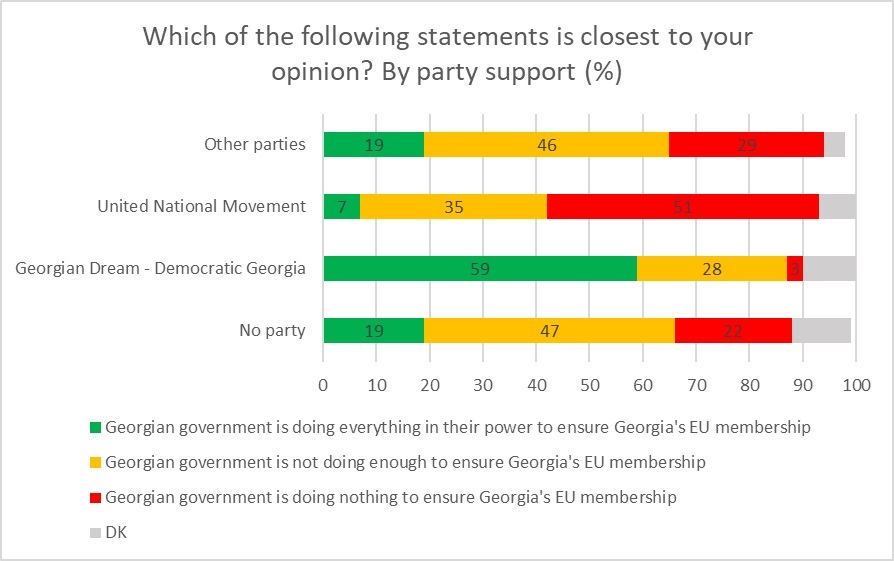

As Georgian officials ramp up their anti-Western rhetoric, recent CRRC Georgia data suggests that most Georgians are uncertain who to blame for the country’s failed European Union membership bid.

On 17 June 2022, the European Commission decided not to grant Georgia EU candidate status, unlike Ukraine and Moldova. In its memo, the Commission recognised the country’s ‘European perspective’, while pointing at an extensive list of issues it needs to address before its candidacy bid is re-examined.

Officials in Brussels later explained that the EU will return to discussing Georgia’s candidacy status ‘sometime in 2023’, by which time the country is supposed to implement reforms addressing political polarisation, the judiciary, and ‘de-oligarchisation’ among a number of other concerns.

Following the announcement, Tbilisi became the epicentre of mass protests attended by tens of thousands of disappointed citizens. Protestors blamed the government for its inaction. Many alleged that the ruling Georgian Dream party deliberately tanked EU membership candidacy talks.

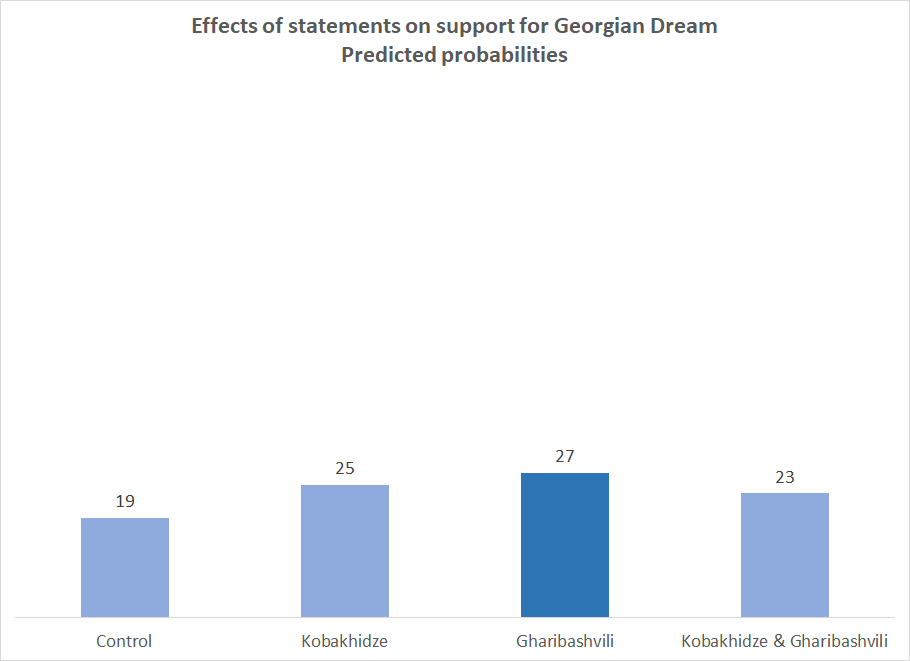

In the lead-up to the announcement, Georgia’s actions placed the bid into question; the country’s political leadership, including the country’s Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili, hinted that they would, “say everything” if the European Union decided ‘unfairly’ on the country’s candidate status.

On the other hand, Irakli Kobakhidze, the chair of Georgian Dream, bluntly stated that if Georgia were to go to war against Russia, it would ‘have been guaranteed EU candidate status by December’. Adding fuel to the fire, the pro-government outlet Imedi ran a poll asking respondents what Georgia should do if the west asked the country to get involved in a war against Russia. Unsurprisingly, the majority said that the country should reject such a proposal.

As emotions have tempered, CRRC-Georgia’s omnibus survey clarifies how Georgians feel about the candidacy status controversy. Fielded in late July, the survey shows that most Georgians reject Georgian Dream politicians’ allegations that the country’s EU membership status was somehow contingent on Georgia’s involvement in a war against Russia.

Instead, people tend to blame the government’s inaction, polarisation, and the country for simply not meeting membership requirements. Yet another rather worrying trend shows a small but statistically significant shift in the support for Georgia’s EU membership.

Who is to blame?

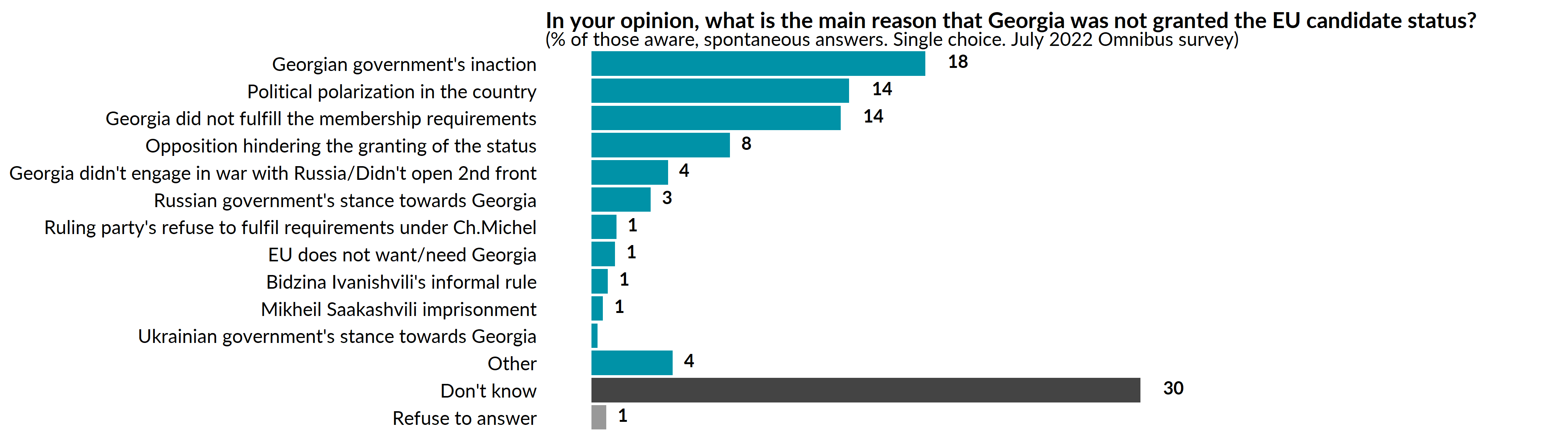

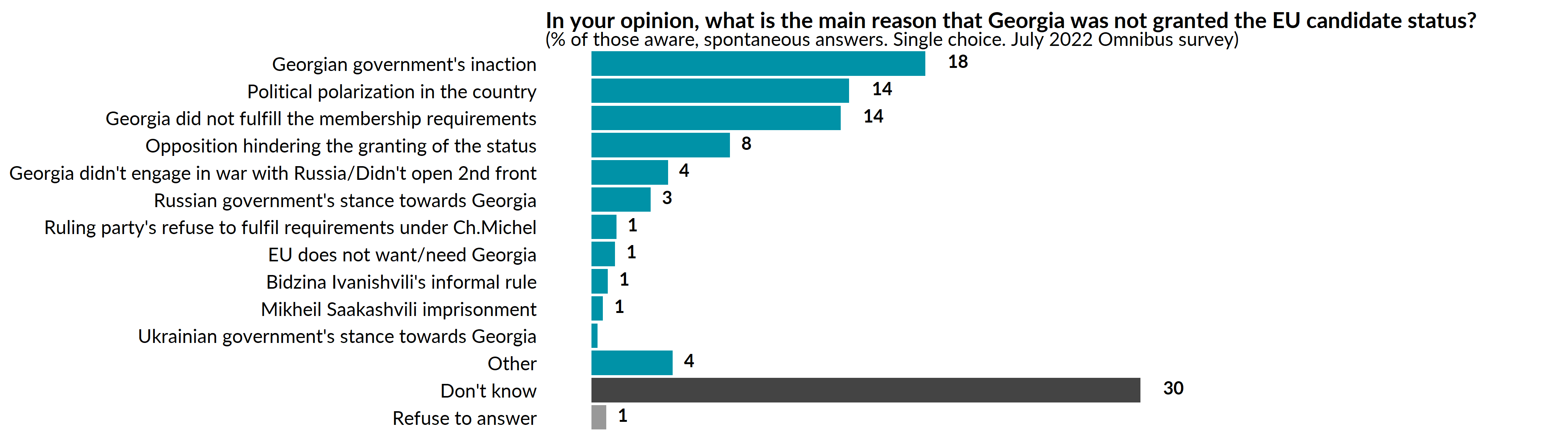

Overall, three-quarters of Georgians (76%) know the EU did not grant Georgia candidate status. Those who knew about it were asked what they thought the main reason behind the European Commission’s decision was. A third (30%) were uncertain. About a fifth (18%) blamed the Georgian government’s inaction, while equal proportions (14%) attributed this to political polarisation in the country and Georgia not fulfilling the requirements set for membership.

A further 8% believed that Georgia was not granted candidate status due to opposition meddling and sabotage. Fewer (4%) said that this happened because Georgia did not get involved in a war against Russia, with 3% blaming the Russian government. Close to 1% named options such as the government not complying with the agreement brokered by the President of the European Council Charles Michel, or that the EU does not need Georgia, Bidzina Ivanishvili’s supposed informal rule, former President Mikheil Saakashvili’s imprisonment, and the Ukrainian government’s stance towards Georgia. Close to 5% named other options or refused to answer.

Does the public believe the West asked Georgia to start a war with Russia?

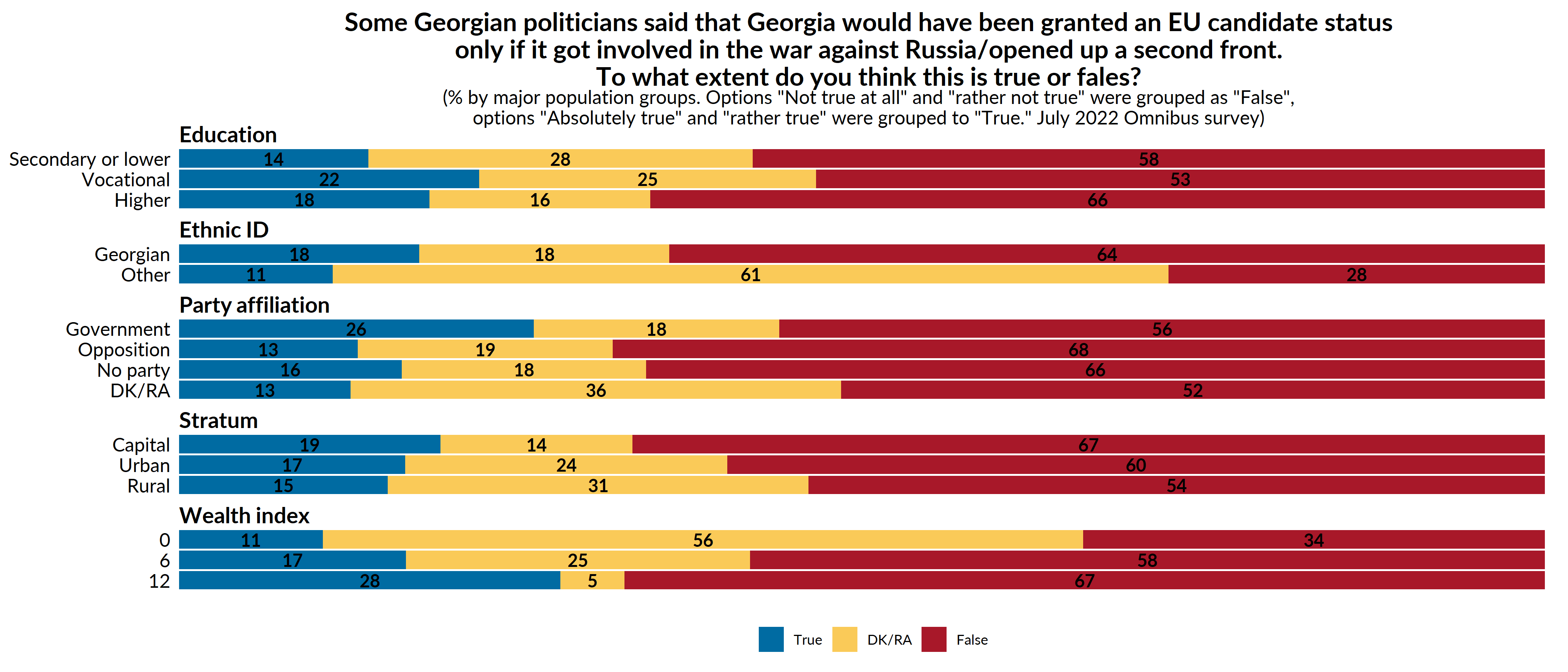

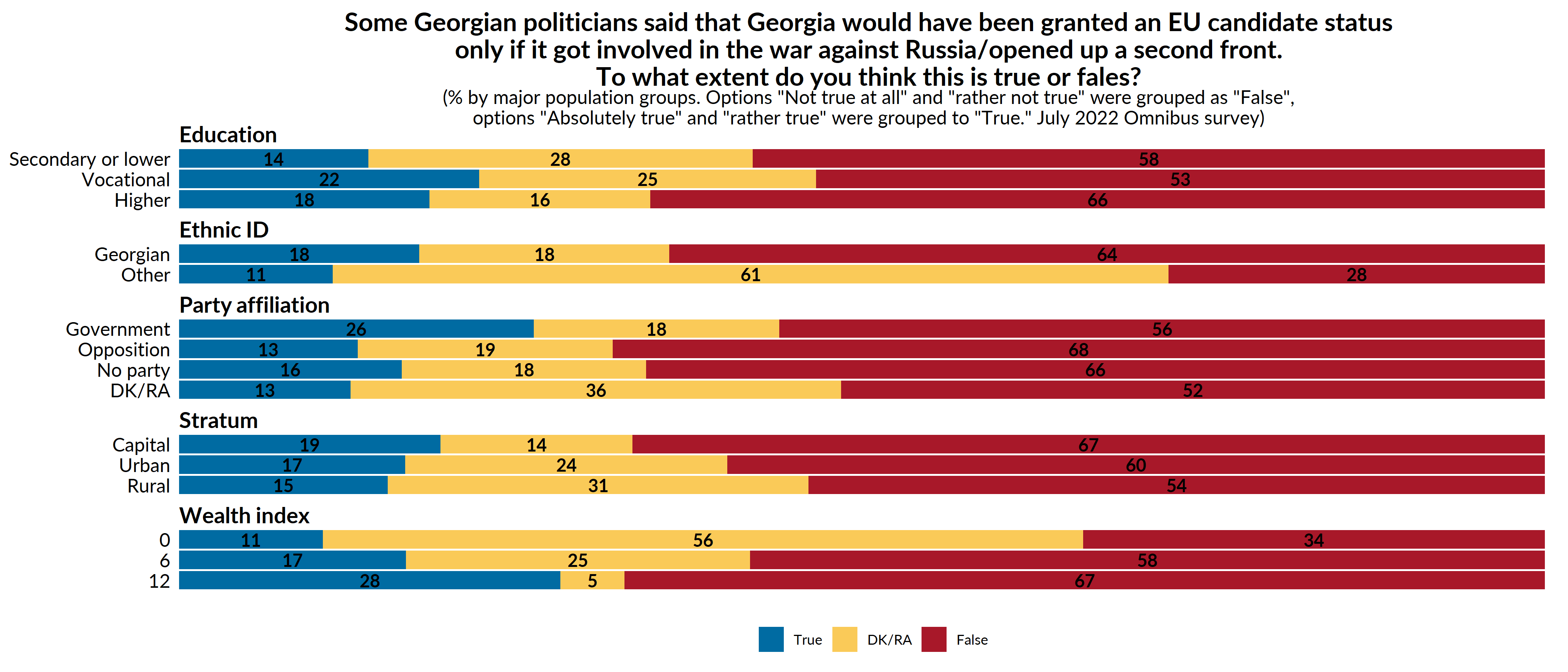

No — most Georgians do not think that the EU candidacy bid was contingent on the country starting a war with Russia. Respondents were initially informed that some Georgian politicians claimed that Georgia would have only become an EU candidate if the country had waged war against Russia or opened a ‘second front’.

Next, they were asked whether or not it was true that Georgia would only be granted candidate status if it was involved in a war. Sixty per cent of Georgians said that this claim was either not true at all or mostly not true. Only one in six (17%) believed that the claim was either mostly or absolutely true. Importantly, close to a quarter (23%) were unsure, while a further 1% refused to answer.

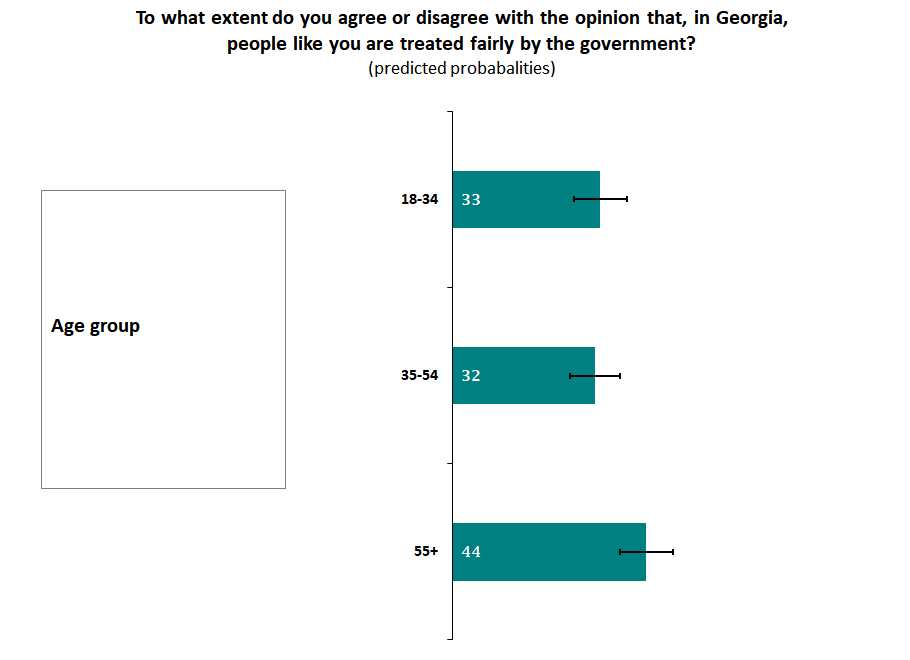

Partisanship, place of residence, ethnicity, wealth, and education predict whether or not someone believed the statement. While a majority across the political spectrum reported that the statement that Georgia would have gained candidate status if it had engaged in a war against Russia is false, about a quarter of Georgian Dream supporters believe in the statement. Almost two-thirds of opposition supporters and those who say that no party is close to their views say that the statement is false. More than one-third of respondents who do not know or refuse to state their political preferences are ambivalent about whether or not the above-mentioned statement is true or false.

Ambivalence predominates among ethnic minorities and those with lower socio-economic standings. Notably, it also declines with increases in wealth: those who are most well-off are also the most polarised when assessing whether or not the statements about Georgia’s involvement in the war are true.

Where to now?

The European Commission handed Georgia an extensive list of priorities it expects the country to deliver on for candidacy status. The poll shows that most Georgians are sceptical that the government will be able to implement the necessary reforms the EU requested.

When asked whether or not they expect the Georgian government to implement the reforms, the plurality (45%) says they do not expect it to happen, with 17% saying they are not expecting reforms to move forward and 29% believing that it is more unexpected than expected by the end of the year.

By comparison, 29% expect the Georgian government to comply with the EU’s recommendations, about a quarter believe that it is more expected than unexpected that the government will implement the reforms, and 4% think that it is totally expected that the government will complete necessary reforms for Georgia’s EU candidacy status. A quarter of Georgians are unsure (25%).

Several civil society activists suggested that a technocratic government should oversee the implementation of the reforms. When asked whether or not they approved of creating a technocratic government tasked with implementing the reforms needed to fulfil the EU candidacy criteria, the plurality (42%) said they disapproved, 29% approved. More than a quarter were uncertain (26%).

Who is an oligarch?

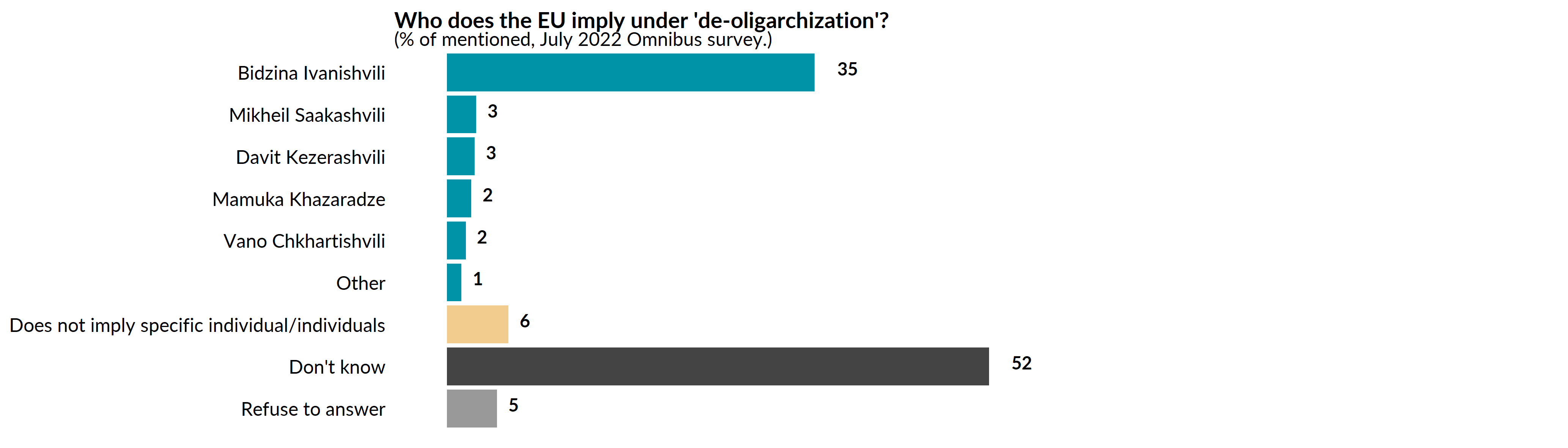

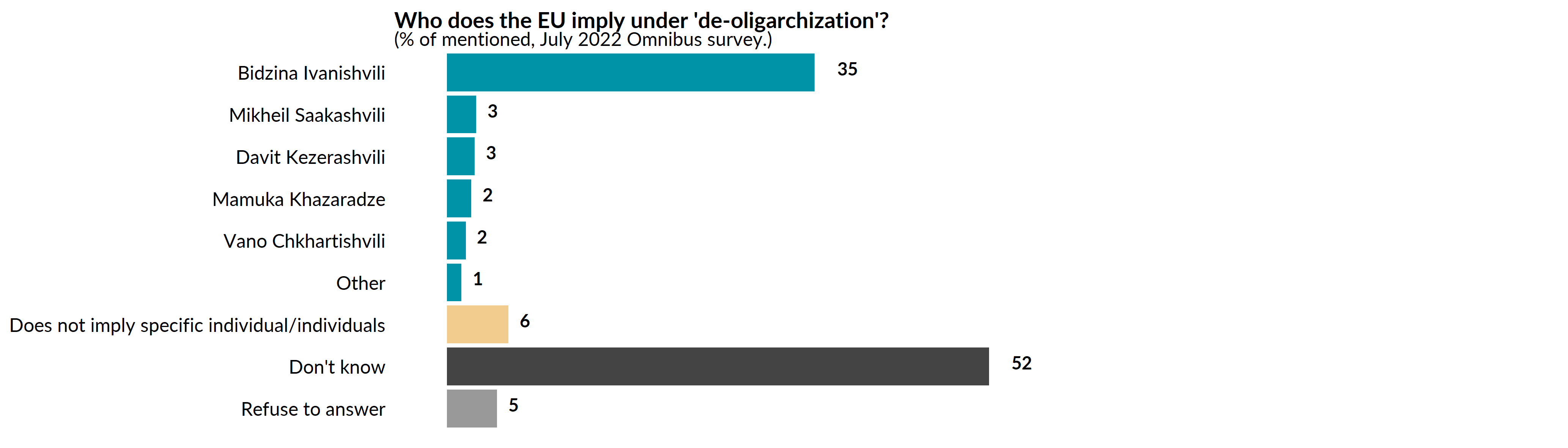

Among the conditions the EU set for Georgia was the ‘implement[ation] of the commitment to “de-oligarchisation” by eliminating the excessive influence of vested interests in economic, political, and public life’.

While the opinion did not give a conclusive answer as to whom the Commission considered to be an oligarch, Georgian officials were quick to respond. In a 12 July Facebook post, Irakli Gharibashvili, the country’s prime minister, fiercely rebuked the suggestion that Bidzina Ivanishvili, the founder of Georgian Dream and a former Prime Minister, is still in charge.

Gharibashvili even penned another letter to Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, where he requested that she distance herself from a European Parliament resolution that called for sanctioning Ivanishvili.

CRRC Georgia asked who the public thinks the EU considers an oligarch in their statement. Notably, more than half said that they didn’t know who the European Commission was hinting at. Among those that did have a concrete response, a third (35%) consider Ivanishvili to be the oligarch in question. Few (3%) named the currently imprisoned Former President Mikheil Saakashvili or Davit Kezerashvili, a businessman and a former defence minister. A further 2% named Mamuka Khazaradze, a co-founder of TBC Bank and the Lelo party, or Vano Chkhartishvili, a Shevardnadze-era businessman and alleged power broker under Ivanishvili.

Interestingly, those who support Georgian Dream (51%), non-partisans (55%), and those that don’t know which party is closest to their views (62%) are more likely to be uncertain, while a majority of the opposition supporters (60%) believe that the EU was singling out Ivanishvili.

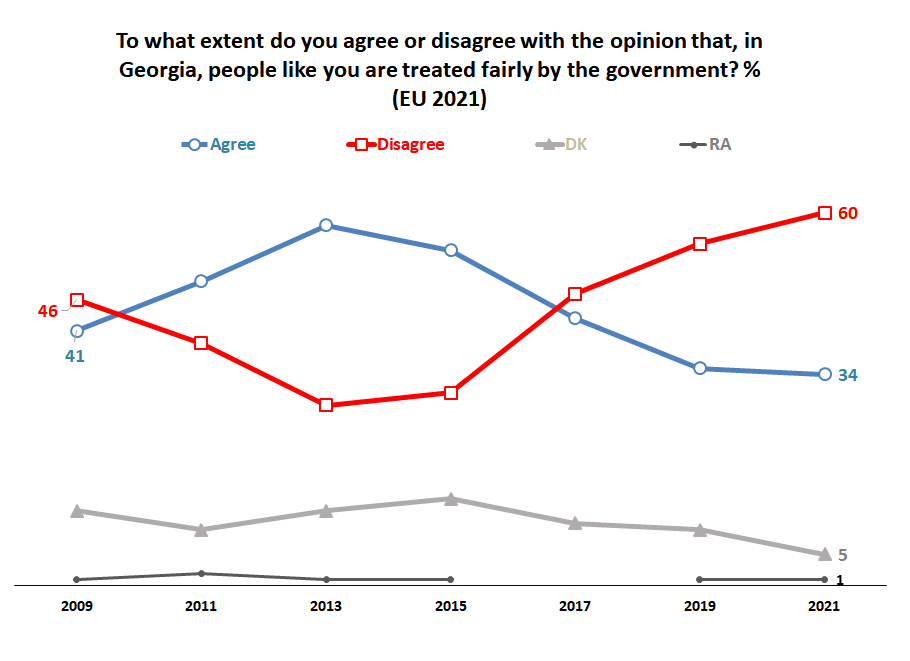

Is Euroscepticism spreading among Georgians?

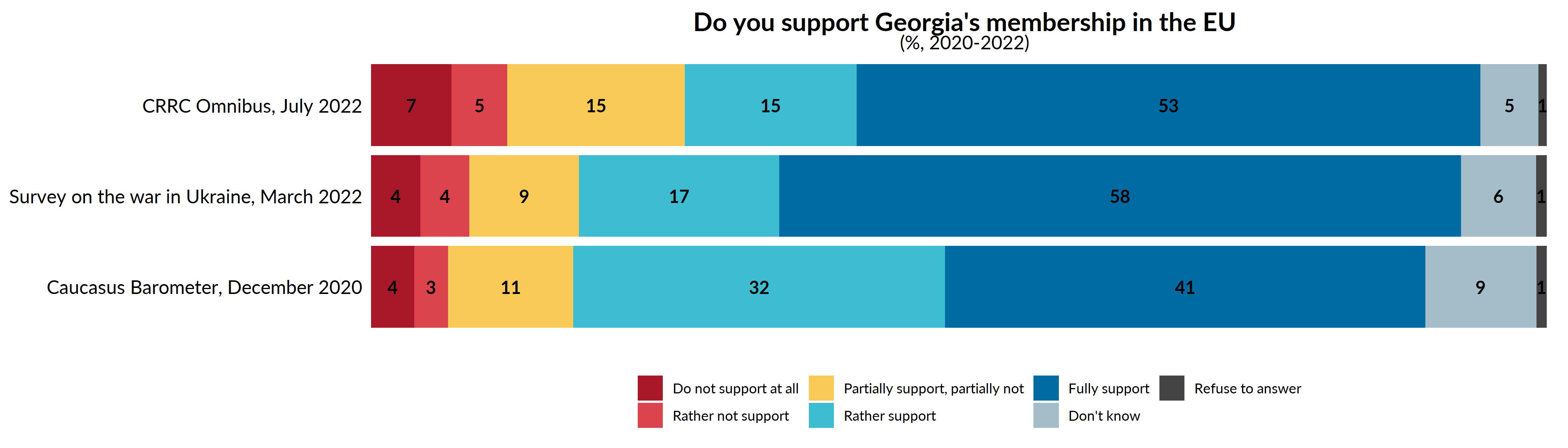

CRRC Georgia’s omnibus survey shows that most Georgians (68%) still support the country’s membership in the EU fully (53%) or partially (15%). This is slightly less, though still broadly comparable, to previous levels of support in earlier surveys. The 2020 Caucasus Barometer showed that five percentage points more (73%) expressed full or partial support for EU membership.

In a similar survey fielded in mid-March 2022, EU support stood even higher at 75%, indicating a seven-point decrease over the course of five months. Still, this finding should be viewed with some caution, given that the surveys had different questions, which in turn can moderate or exaggerate support.

The decline in support for Georgia’s EU membership appears to stem from changing views among Georgian Dream supporters. In the 2020 Caucasus Barometer survey, Georgian Dream supporters backed Georgia’s EU membership by eight percentage points more compared to the July 2022 survey (68%).

Many in Georgia are afraid that the controversy surrounding EU candidacy might undermine public support for Georga’s EU membership. CRRC Georgia’s omnibus poll paints a rather complex picture. EU support runs high, and the majority disagrees with the baseless allegations that the West is dragging the country into a war against Russia. Nevertheless, survey results hint that some Georgians, particularly supporters of Georgian Dream, might be questioning their support for the EU. Whether this is the start of a real shift in public opinion or a statistical blip remains to be seen.

Note: Differences across groups are identified using regression models. Reported figures might not sum up to 100 due to rounding errors. A replication code for the analysis above is available here. Marginal frequencies and crosstabulations are available here.