Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Eto Gagunashvili, a Researcher at CRRC-Georgia, The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

Recent CRRC Georgia data suggests that people in Georgia’s age and foreign policy preferences affect how they feel the government is treating them.

The public’s perception of the fairness of the government’s actions is critical to governance and may reflect the quality of democracy in a country. Today, Georgians tend to feel like their country is no longer a democracy, while the public feels that people like them are not being treated fairly by the government.

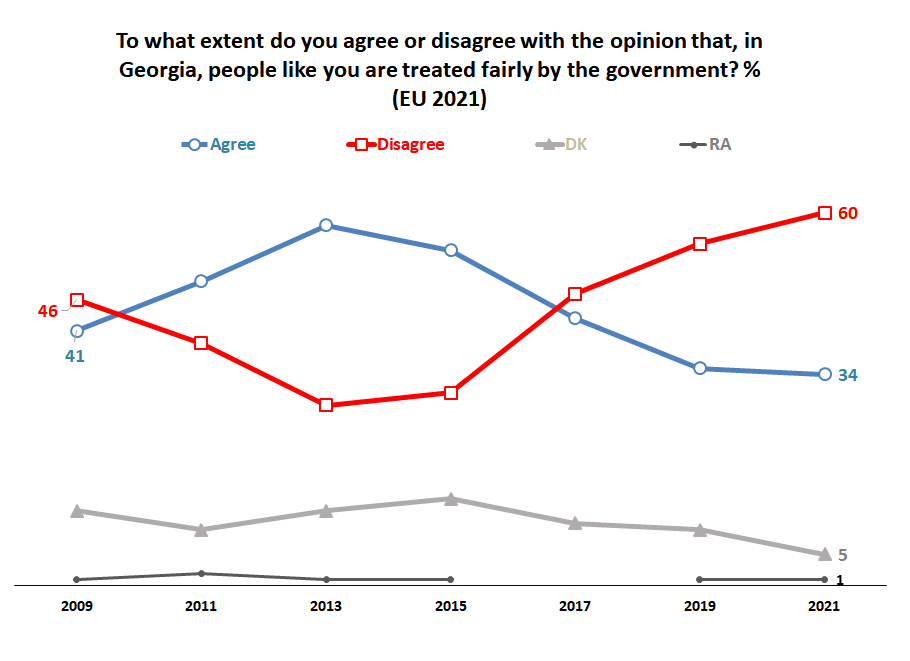

According to data CRRC Georgia collected for the Europe Foundation since 2009 through a survey on Georgian attitudes towards the EU, the share of Georgians who disagree with the opinion that people like them are being treated unfairly by the government has increased from 46% in 2009 to 60% in 2021.

Today, twice as many people think that the government treats people like them unfairly as those who feel otherwise.

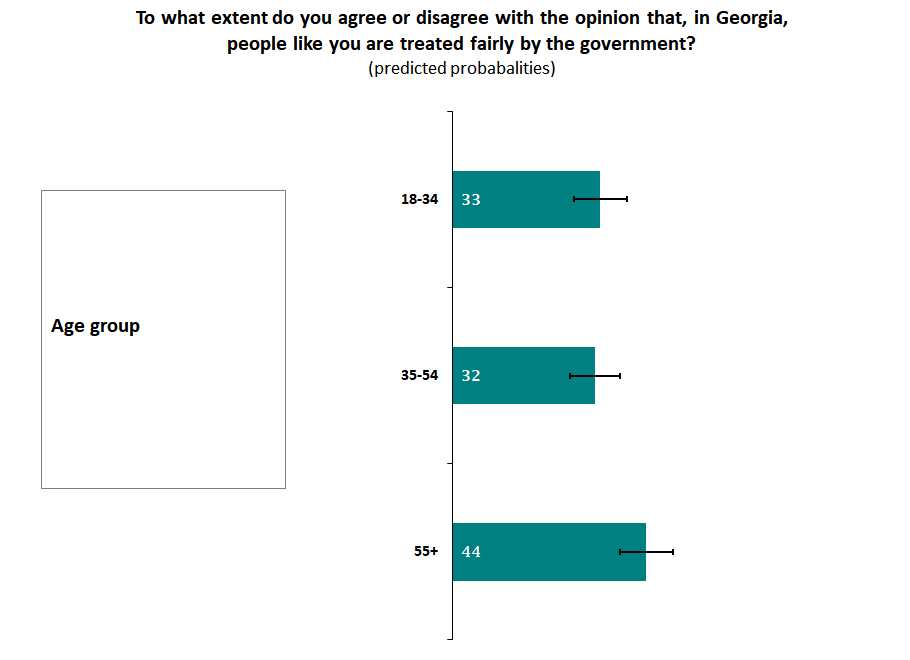

In the 2021 data, older people (55+) were more likely to agree with the opinion that in Georgia, people like them are treated fairly by the government than younger people (18–35). Other social and demographic variables were not statistically associated with whether or not someone thinks the government treats someone like them more or less fairly.

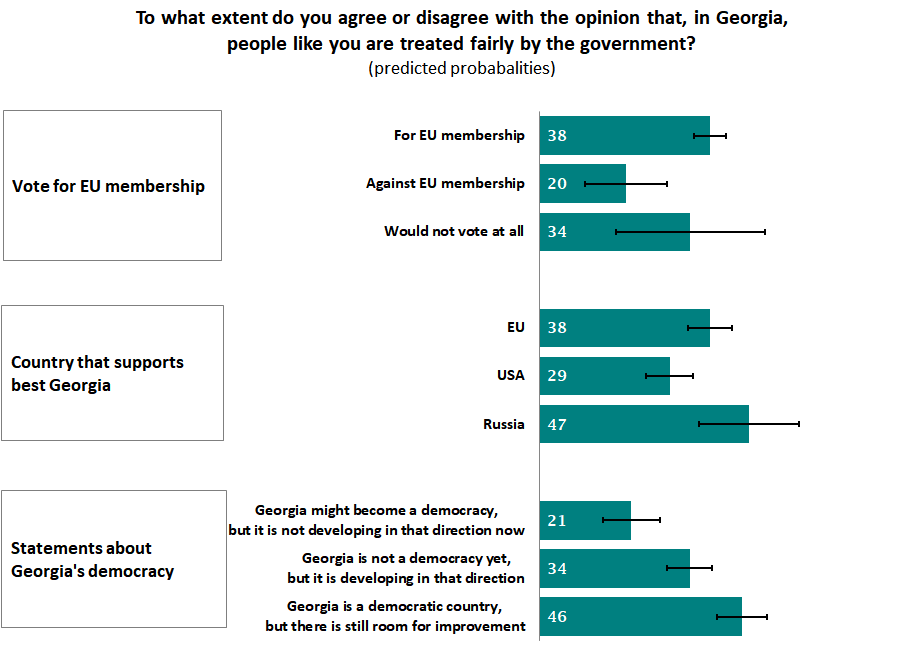

People’s perceptions of how democratic Georgia is, which country can best support Georgia currently, and support for EU membership are correlated with people’s views of whether people like them are treated fairly by the government.

People who report that they would vote against EU membership were 18 percentage points more likely to agree that the government treats them fairly than those who report that they would vote for EU membership.

People who report that the USA can currently give the best support to Georgia were 18 percentage points less likely to agree with the statement that people are treated fairly by the government compared to people who report that Russia can best support Georgia.

People who think that Georgia is not a democracy yet, but is developing in that direction or think that Georgia is a democratic country with room for improvement were 13 and 25 percentage points more likely to agree that they are treated fairly than people who think that Georgia might become a democracy in the future, but it is not developing in that direction now.

With the perception that Georgia’s democracy is backsliding, so too comes the public perception that the government is increasingly not treating people like them fairly. However, older people and people who think Russia can best support Georgia were more satisfied with how the government treats them.

Note: The above data analysis is based on logistic regression models which included the following variables: age group (18-34, 35-54, 55+), sex (male or female), education (Secondary or lower; Secondary technical; Higher; type of settlement (capital, urban, rural); who can currently best support Georgia (EU, USA, Russia), how democratic Georgia is (Georgia might become a democracy in the future, but it is not developing in that direction now; Georgia is not a democracy yet, but it is developing in that direction; Georgia is a democratic country, but there is still room for improvement); Agree/disagree with the statement: "I am Georgian, and therefore I am European”); Would vote for or against EU membership? (For EU membership; Against EU membership; Would not vote at all).