Wednesday, November 02, 2011

A Further Look at Material Deprivation

Posted by

Vitaly Radsky

at

7:13 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Economy, Poverty

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Gender | How Does the South Caucasus Compare?

Posted by

HansG

at

8:49 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Gender, Pew Research Centers

Friday, October 07, 2011

Class in the Caucasus | Article by Ken Roberts and Gary Pollock

Using data from the Caucasus Barometer, Ken Roberts and Gary Pollock argue that "in economic and socio-political terms there are as yet just two real classes among actual and potential employees in the South Caucasus – middle classes and lower classes – and that although these classes differ in their standards of living and political dispositions, these are unlikely to become bases for conflict between them."

Interested in more detail? Check the abstract online.

Posted by

HansG

at

5:49 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

Ask CRRC!

When presenting our work, or talking about it informally, we are asked fairly similar questions: do you do your interviewing in all of the country? How do you select the respondents? How do you know they are not lying to you? Are people willing to say things critical of the government? How do you design a questionnaire?

These are extremely important questions, because they will influence whether you can take our survey results at face value. As mentioned in the last post, we have decided to give you more regular updates on what we do, and how we do it.

This, too, was another lesson we learned from our favorite role models, the Pew Research Centers. They have a specific section called "Ask the Expert", pictured below.

What, then, has always puzzled you about survey research? Let us know, either through the comments or by writing an e-mail. We will, eventually, make this information available in the local languages as well. Your input will help us identify the questions people have.

So, what questions do you have for us?

Posted by

HansG

at

12:04 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Research, Survey

Friday, August 13, 2010

Religious Service Attendance: An ESS/CB Snapshot

By David McArdle

Earlier this week, The Economist pointed out some data from the 2008 European Social Survey (ESS) on attendance at religious services across Europe. Collating the answers on attendance from 28 countries in order to ascertain one aspect of religious observance, the results showed that the Czech Republic had the highest percentage of people who said they never attend services, apart from special occasions such as weddings and funerals.

Using the 2009 CB data, which has the same question on attendance, we included the countries of the south Caucasus to see how they fit vis-à-vis their European counterparts. Georgia is the country in the south Caucasus with the fewest people who say they never attend services (11 percent). Georgia, therefore, was fourth in the list behind Cyprus, Greece (both predominantly Greek Orthodox), and Poland (almost exclusively Roman Catholic).

Next came Armenia (21 percent) and then Azerbaijan (29 percent), with more moderate levels of religious service attendance. As shown on the graph below, Armenia’s figure was just below Turkey’s, while Azerbaijan’s was closer to Estonia’s.

While this is just one way to measure religious observance, it offers a glimpse of how people are practicing throughout Europe. The ESS has much data to discover, which can be done using its easy-to-use format, available here. Meanwhile, our own Caucasus Barometer also has similar questions, on rates of fasting (2009) and prayer (2007), for instance. For more information on these, get in touch with us, or explore the data on our interface here. Finally, to check out The Economist's article, go here.

Posted by

Anonymous

at

10:23 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Europe, Religion, South Caucasus

Sunday, August 08, 2010

Respondent Evaluation | A Great Tool for Looking into Survey Interviews

While we know that particular wordings may lead to slightly different interpretations in different languages, the interviewer ratings give us a glimpse into what is going on, and thus help us improve the quality further. Survey work is nearly never perfect. It's a process of continuous improvement. Plenty of opportunities for researchers to analyze the data more closely.

Posted by

Moritz Baumgärtel

at

12:27 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Caucasus Barometer, Data, Data Initiative, Georgia, Respondent Evaluation

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Attitudes toward the West | Caucasus Analytical Digest

Following an article on Georgians’ attitudes toward Russia, CRRC Fellows Therese Svensson and Julia Hon have written a new piece for CAD, entitled “Attitudes toward the West in the South Caucasus”. Their article looks at citizens’ views on three areas of relations — political, economic and cultural — between the South Caucasus and the West, in particular NATO, the US and the EU. The data were derived from the South Caucasus–wide 2007 and 2008 Data Initiatives (DI), as well as from the 2009 EU survey that was conducted in Georgia.

The article highlights several figures which show that citizens in the South Caucasus, and especially those in Georgia, are keen to cooperate with the West on economic and political levels. For example, on a ten-point scale — where '10' equals full cooperation and '1' is no cooperation — 80 percent of the Georgian respondents ranked their desire for economic cooperation with the U.S. in the top five categories, compared with 71 percent in both Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The percentages on potential NATO membership, by contrast, vary more widely in the three countries: while 42 percent in Georgia said they are fully in favor of membership, 21 percent said the same in Azerbaijan, and only 10 percent in Armenia.

But the most fascinating figures arise when the subject of cultural relationships comes up. Although citizens in the South Caucasus are open to friendship and doing business with citizens of the West, they seem less keen on Western cultural influences, which they view as potential threats to their own cultural identity and traditions. In all, 64 percent and 63 percent in Armenia and Azerbaijan, respectively, either strongly or somewhat agreed with a statement that "Western influence is a threat to [national] culture". Twenty-four percent in Georgia said the same, while 34 percent chose "neutral" as their answer.

Perhaps understanding exactly which elements of Western culture are seen to be threatening, and in what way, would be a topic of additional interest.

For the full article, go here.

Posted by

Anonymous

at

5:44 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Attitudes, Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, NATO, South Caucasus

Thursday, June 17, 2010

Greatest Threats Facing the World | Data from the 2009 CB & the Global Attitudes Survey

Posted by

VazhaB

at

5:48 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Child Poverty, Data Initiative, Development, HIV/AIDS, Pew Research Centers, Survey

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Caucasus Barometer | A New Name for the CRRC's Data Initiative

The Data Initiative was first launched in 2004. Since 2007, a representative sample of approximately 2,000 respondents is interviewed annually in each of the counties. They answer core questions about household composition, social and economic situation of households, employment status, assessments of social and political situation in the countries, as well as respondents’ perceptions about direction of life. In addition, we include questions about media, health, crime, and other topical issues.

The change of the name, however, will not cause any changes in the way the survey is carried out – it is still an annual survey conducted every fall in all countries of the South Caucasus, employing the same methodology and the same survey instrument. Its major goal is to get reliable longitudinal empirical data to understand various aspects of the processes of social transformation in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. We are committed to ensure the highest possible scientific quality through all the steps of survey implementation.

The data and the survey documentation are open to all interested researchers and represent a unique tool for further quantitative analysis. You can find more information about the Data Initiative/Caucasus Barometer on our website.

Posted by

Nana

at

3:42 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data, Data Initiative, Household, South Caucasus, Survey

Monday, May 03, 2010

The Level of Trust in Government Institutions in Georgia: The Dynamics of the Past Three Years

Posted by

VazhaB

at

12:11 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Georgia, Institutions, Trust

Friday, February 12, 2010

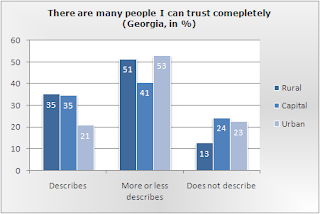

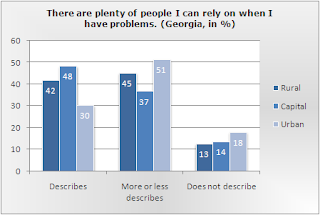

Social networks in rural and urban Georgia

It is often stated that life in a city is fundamentally different from that in rural areas. In the West, village life is said to be more intimate, and its inhabitants more caring about their peers, with strong ties between neighbors and family members. Can this also be said in the South Caucasus? After all, family relations and friendships are supposed to be strong in countries like Georgia. Do these ties reach into the cities, erasing the difference between strong social networks in rural areas and the more anonymous, independent urban setting?

The data from our 2008 Data Initiative (DI) gives us several clues as to how to answer this question. Georgian respondents in three settlements types - rural, urban (excluding the capital), and Tbilisi - were asked about their views on their social environment. The results showed that people with positive feelings about their social networks were, contrary to our expectations, most likely to be found in the capital, but least likely in other urban areas.

According to our data, inhabitants of rural settlements and Tbilisi are most likely to have enough people to trust. Villagers also have the lowest percentage of people lacking this kind of social support. Our question asked the respondents whether they had “many people to trust completely.” Respondents were most likely to agree with this statement in rural areas and Tbilisi (both 35 percent). Urban Georgia came out last, where only 21 percent felt they had trustworthy people around. By contrast, 24 percent in Tbilisi and about 23 percent in other urban areas said they cannot trust many people in their social environment. In rural Georgia only 13 percent of respondents said the same. The neutral answer reading “the statement more or less describes my feelings” was most often recorded in urban areas (53 percent), followed by rural Georgia (51 percent) and Tbilisi (41 percent).

When asked about people close to them, respondents in Tbilisi were more often satisfied with their situation than those living in other settlement types. Inhabitants of rural areas were least likely to express a lack of close friends. In response to the proposed statement “I have enough people I feel close to”, urban Georgia had again the least favorable response pattern. In cities like Batumi or Rustavi, only 41 percent of respondents stated that they have many close people around. Fifty percent in the capital and 45 percent in rural areas agreed with this statement. This time, Tbilisi also had the highest percentage of negative answers, with as much as 13 percent of the respondents thinking that they lack close friends. Only 9 percent of answers recorded in rural parts of the country, and only 10 percent in urban Georgia, reflected the same negative feelings. The neutral answer was most likely to be found in rural settings and urban areas (both 46 percent), followed by the capital (37 percent).

In response to the statement “there are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems”, once again more people in the capital than in other parts of Georgia agreed, and urban Georgia featured the highest percentage of respondents who miss reliable people when they encounter problems. In urban Georgia only 30 percent of the respondents felt safe to turn to their friends when in trouble, and there were 18 percent who thought that they cannot rely on their social environment in this way. Both in the capital and in rural areas, the spread between positive and negative answers is much higher: in Tbilisi a full 48 percent agreed that they have plenty of reliable people around, compared with 14 percent who disagreed. In rural areas 42 percent gave a positive and only 13 percent a negative answer. The percentage of respondents who chose “describes more or less my feelings” as their answer was lower in the capital (37 percent) than in rural (45 percent) and urban Georgia (51 percent).

Now, which settlement has the highest quality of social networks? If we take a negative definition (i.e. we search the type of settlement with the smallest percentage of respondents expressing a lack of sound social ties), rural life seems to be the best choice, with the fewest amount of people choosing the negative answers. If, however, we compare positive answers (i.e. we search the type of settlement where the highest percentage of respondents were satisfied with their social networks), the capital is ahead of rural settlements. With both definitions, urban Georgia (excluding the capital) comes out last in the comparison. This hints to the fact that city life might have significant drawbacks, but that they have been compensated in Tbilisi by factors not present in other urban settlements. By the way, people in the capital also tend to have a more pronounced opinion about these matters, with fewer respondents choosing the neutral answer in response to the three statements.

What are the factors that help Tbilisi to counterbalance some of the negative aspects of city life? Why does it have so many people satisfied with their social networks, without the large numbers of unsatisfied respondents found in other cities in Georgia? Some of these factors might be found with the help of our survey data. If you feel like exploring this interesting subject, or would like to see similar data for Armenia or Azerbaijan, we invite you to visit http://www.crrccenters.org/sda, where you can find all of our 2008 DI survey data for free, accessible via an easy-to-use web interface. Comments and ideas are appreciated.

Posted by

Malte

at

3:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Civil Society, Data, Data Initiative, Georgia, Perceptions, Sociology

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Insight to Georgian Households | CRRC Data on Economic Wellbeing in the Caucasus

We again (see our recent piece on social developments here) published something in Investor.ge, the journal published by the American Chamber of Commerce -- and a great resource for tracking business and economic developments.

In this article, Arpine and Nana discuss how much Georgians earn, what they spend money on, how they borrow, and how they see their financial future. Read the article on economic well-being of Georgian households here.

Posted by

Nana

at

11:55 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Business, Caucasus Barometer, Data, Data Initiative, Economic Situation, Household

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Religiosity and Trust in Religious Institutions | Paper with CRRC Data

However, the results show some differences between the three countries with regard to two types of control variables-trust in secular institutions and socioeconomic factors. Georgia is the only country in which interpersonal trust is a significant indicator of trust in religious institutions. Residence in the capital is only significant in Azerbaijan. Armenia is the only country in which both education and age are significant.

To read the actual paper, which also tests two theories of trust in institutions, click here.

Posted by

Arpine

at

6:45 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Data, Data Initiative, Religion, Survey

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

The South Ossetia Crisis: a War of Ideologies

It is therefore noteworthy that public opinion plays a key role in a recent article by Anar Valiyev, entitled “Victim of a ‘War of Ideologies’ - Azerbaijan after the Russia–Georgia War”. Because of the war, Valiyev argues, Azerbaijanis have become less supportive of Western-style “unmanaged” democracy, preferring instead a more controlled and Moscow-backed “sovereign democracy”.

Interestingly, he asserts that the Russia-Georgia war “significantly changed Azerbaijanis’ perceptions of the democratic West and negatively impacted their perceptions of the United States and the European Union. Georgia’s defeat and the subsequent political turmoil demonstrated the viability and stability of the sovereign democracy and made the Russian model of governance more attractive to the people of Azerbaijan.”

In order to illustrate this premise, Valiyev places a great emphasis on public opinion polls, including CRRC’s Data Initiative. He emphasises the value of these statistics, noting that they are almost the only method enabling to track the political development and the perceptions of the Azerbaijani society before and after the South Ossetia crisis.

For one, surveys held by CRRC show an interesting change in Azerbaijani public support for NATO membership. Whereas about 60 percent of the population supported NATO membership in 2006 and 2007, only 48 percent of the respondents supported the military block in November 2008. At the same time, the share of the population that was neutral on the question rose significantly. To Valiyev, this increasing undecidedness about joining NATO is a direct result of the West’s failure to effectively engage with Russia during the South Ossetia war.

Azerbaijani public support for EU membership was characterised by a somewhat similar development. The year 2008 saw a sharp increase in the percentage of people taking a neutral stance on potential EU membership for Azerbaijan (from 37 to 48 percent), while there was a decline in both the percentage of people supporting and the percentage of people not supporting EU membership. This shift indicates, Valiyev concludes, an increasing confusion among the Azeri public about the role of the EU in the Caucasus.

Other CRRC statistics used by Valiyev demonstrate how public trust in the Azeri armed forces dropped from 81 to 68 percent between 2007 and 2008, and how President Aliyev’s popularity rose to a record 82 percent after the war. Some additional survey material refers to popular support for enhancing economic relations with Western countries and Russia.

There is no conclusive answer as to whether the developments in public perception are a direct result of the Russia-Georgia war. However, Valiyev’s article makes for an engaging read, and highlights the value of survey data to expose the ideological dimension of conflict.

We recommend you to read the article at: http://heldref-publications.metapress.com/app/home/contribution.asp?referrer=parent&backto=issue,4,4;journal,1,23;linkingpublicationresults,1:119920,1

Alternatively, it can be found in Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization (Issue: Volume 17, Number 3 - Summer 2009).

Posted by

Jonne

at

3:08 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Attitudes, Azerbaijan, Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, South Ossetia

Monday, October 26, 2009

Health issues in the South Caucasus

The most striking difference between the countries is that Georgians consider the availability of affordable medicines to be the most urgent health problem (23.5 percent), but only 5.0 percent of the respondents in Azerbaijan agree with this being the most pressing health issue. The next interesting difference can be found in people’s perceptions of heart diseases. The respondents in Armenia and Azerbaijan believe this is one of the most urgent problem (19.1 percent and 16.2 percent, respectively), but only 7.5 percent of the respondents in Georgia agree with this. Moreover, a difference can be seen in people’s perceptions of diabetes and tuberculosis. Respondents in Armenia and Georgia do not state tuberculosis as one of the most pressing health issues (2.7 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively), but 9.6 percent of the respondents in Azerbaijan believe it to be of urgent concern. Finally, only 1.7 percent of the respondents in Georgia say diabetes is the most pressing health issue, while the same level of respondents in Armenia and Azerbaijan is 6.6 percent and 11.7 percent, respectively.

This is merely a data snapshot, and of course CRRC’s Data Initiative is not an instrument specifically designed to capture data on public health. Nevertheless, it yields valuable insights and even more information on health-related topics in the South Caucasus can be found by accessing the datasets on CRRC’s webpage. You can for example find out differences in perception of health issues between men and women, how satisfied people are with the medical healthcare, and information about smoking habits – as well as analyze in more detail the characteristics of different groups of respondents according to age, economic status and place of residence.

Posted by

Therese Svensson

at

5:17 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Attitudes, Azerbaijan, Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Georgia, Public Health

Monday, April 06, 2009

Banking and Financial Services in the Caucasus | CRRC Data

As one can see in the graph above, banking/financial services are not used by the majority of the DI’s respondents. 66% in Georgia have not used banking/financial services compared to 57% in Armenia and 53% in Azerbaijan. Not many households are at risk of having their savings eaten up since only 1% of households in the region have savings accounts. It is remarkable that loans have been taken by so many Armenians (18%), but note that these people may not be owing money right now. For a look at household exposure, check our older post.

As one can see in the graph above, banking/financial services are not used by the majority of the DI’s respondents. 66% in Georgia have not used banking/financial services compared to 57% in Armenia and 53% in Azerbaijan. Not many households are at risk of having their savings eaten up since only 1% of households in the region have savings accounts. It is remarkable that loans have been taken by so many Armenians (18%), but note that these people may not be owing money right now. For a look at household exposure, check our older post.

We also have data on public trust towards banks. But here one important limitation of the data above is that it is from 2007, so that it may not be sufficiently up to date. However, the DI 2008 will soon be available online (and yes, if the data show large inconsistencies, there will be a blog post on it). For the data above, check the CRRC Data Initiative (DI) 2007.

We also have data on public trust towards banks. But here one important limitation of the data above is that it is from 2007, so that it may not be sufficiently up to date. However, the DI 2008 will soon be available online (and yes, if the data show large inconsistencies, there will be a blog post on it). For the data above, check the CRRC Data Initiative (DI) 2007.

Posted by

Cemal Ozkan

at

1:19 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Banking, Caucasus, Caucasus Barometer, Credit, Data Initiative, Finance

Tuesday, March 03, 2009

Gallup: Azerbaijan is One of Least Religious Nations

How does religiosity in Azerbaijan look according to CRRC Data Initiative (DI)? According to our dataset, 97,2% of Azerbaijani identify themselves as Muslims, although this does not mean that religion is practiced on a daily basis by all of them. 14% of the Azerbaijani respondents pray every day, 30% admit that they do so “less often” and 25% of the Azeri’s say that they never bow in the direction of Mecca.

How about practice of religion in Azerbaijan from a regional perspective? Indicators determining importance of religion in people’s decision-making show that neighboring Armenians attach the same weight to religion as the Azerbaijani. Georgians, on the other hand, indicate that religion plays a much more important role in their daily lives in contrast to its two neighboring nations. For a more elaborate cross South Caucasian comparison on religious practices, check out this previous CRRC blog post.

Our dataset can not provide a conclusive answer to the second question on why the Azerbaijani lifestyle tends to be secular to its nature. One could point to the effects that Soviet rule might have had on expression of religiosity or that Azerbaijani, in general, perceives Western concepts of secularization and modernization as ideals. However, the depth of Azerbaijan’s secularity has also a pre-Soviet history to it. The country’s own version of Islam, one that has been heavily influenced by Sufi mystics over the centuries, has contributed to the un-dogmatic interpretation of religious decrees that is characteristic for secular nations, such as Azerbaijan.

Posted by

Cemal Ozkan

at

9:54 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, Caucasus Barometer, Data, Data Initiative, Index, Religion

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Securing Personal Safety in the Caucasus | CRRC Data

In Armenia, ironically, criminal leaders have top positions in the chart of groups/institutions that effectively secure personal safety of the population with 22% of the respondents evaluating them positively. Criminal leaders are not far from the police; moreover, while a similar percentage of respondents (22.1% vs. 22.9%) finds Ombudsmen and criminal leaders effective in securing personal safety, more respondents actually find Ombudsmen ineffective, by comparison with criminal leaders (52.3% vs. 47.1%).

Among the three South Caucasus countries Armenia shows the lowest level of trust in the police, while the highest level of trust being observed in Azerbaijan – almost 60%. Trust in the police in Georgia is not very high considering the fact that it is seen as one of the main successes of the post-revolution government. From our data we can see that the trust in police had decreased after the murder case of Sandro Girgvliani in 2006, but it is going up again.

CRRC DI allows exploring this topic further by looking at other components such as how relatives, friends or the Prosecutor’s office secure personal safety. More comparisons (age, settlement type, education, and so on) can be done thanks to the rich demographic bloc. Time comparison is also possible, since we have some data starting 2004. The datasets are available at CRRC website.

CRRC DI allows exploring this topic further by looking at other components such as how relatives, friends or the Prosecutor’s office secure personal safety. More comparisons (age, settlement type, education, and so on) can be done thanks to the rich demographic bloc. Time comparison is also possible, since we have some data starting 2004. The datasets are available at CRRC website.

Posted by

Arpine

at

4:07 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Caucasus Barometer, Data Initiative, Georgia

Monday, October 20, 2008

Comparing Civic Participation: Caucasus Data 2007

We seem to be seeing different patterns in the three countries. Print media, for example, is read a lot less in Azerbaijan than in the neighboring countries.

But of course, that could just be due to particular quirks: more television, or a bigger country in which relevant media does not make it out to the countryside. Just a blip? No, apparently not.

Azerbaijanis indeed are less engaged in events. Few say that they discuss what is going on politically. One reason may be that they live in much more homogenous political space.

Generally, levels of civic engagement are low. This recalls, of course, Robert Putnam's Making Democracy Work, which says that civic association forms the basis of both political (in the sense of good governance: public health, education, policing, and so on) and of economic success. Conversely, a people caught in amoral familism will find it hard to collaborate to improve their communities; and since the majority of real public goods can only be attained by collective action, this could be a serious constraint on improving livelihoods.

On that level, we are extremely glad that we have captured this data. It will allow us to track changes over time.

But is the news all bad? Actually, no. Azerbaijan sees quite some volunteering. As rumor has it, the communal subotnik which brings communities together to clean up and improve the neighbourhood still is alive in some places (although volunteering may be encouraged top-down). See the data:

And in a similar vein, there are contributions to charity in Azerbaijan. In part, this may be because tithing (giving one tenth) to charity is mandated under Islam, and (as you may recall from our previous post) about 15% in Azerbaijan actually say that they pray every day. That almost adds up.

What we are describing, ultimately, is a fascinating research agenda: filtering out who the socially active people in a community are, and what makes them different, and how they were mobilized, and how this could be replicated.

Our data set, for anyone who wants to take that stab, is online, and more data on similar questions will follow soon.

Posted by

HansG

at

6:27 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Civil Society, Data Initiative, Politics, Social Capital, Sociology

Thursday, October 09, 2008

South Caucasus Data 2007 on Unemployment

According to CRRC’s dataset, about 25% of the adult population in Armenia and Georgia, and 20% of Azerbaijan’s citizens say they are unemployed. Further analyzing these numbers shows that 18% in Georgia, 14% in Armenia and 12% in Azerbaijan are actually interested in looking for a job.

[Note: excluded are “students", "housewives", "disabled" or "retired" - even if they are looking for a job.]

[Note: excluded are “students", "housewives", "disabled" or "retired" - even if they are looking for a job.]

However, the data impressively illustrates that the major interest -- among those that are not employed -- in a workplace can be found in urban areas, where about 40% of Armenians and Georgians, and almost 50% Azerbaijanis try to find work. This figure powerfully underlines the desolation of Caucasian cityscapes.

Finally, the DI statistics show that the same number (once you factor in the margin of error) of people is unemployed and interested in a job, but not currently looking: 6% in Armenia, and 5% in Georgia and Azerbaijan. A slightly lower number of the unemployed is not looking for a job at all. Have those already given up?

Now the definitions of unemployment always are a little complicated (are pensioners looking for work considered unemployed?), but here is an article that can help. If you are interested to check the datasets yourself , please download it from CRRC’s homepage. For more information on the Data Initiative project, please click here.

Posted by

AnnaB

at

11:44 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Attitudes, Azerbaijan, Caucasus, Caucasus Barometer, Data, Data Initiative, Employment, Georgia, Poverty, Statistics