Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dustin Gilbreath, David Sichinava, Anano Kipiani, Kristina Vacharadze, Nino Mzhavanadze, and Makhare Atchaidze, CRRC Georgia staff members. The views presented within the article reflect the views of the authors' alone, and do not reflect the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has shocked the world. The war also shook Georgia, with new polling from CRRC Georgia revealing the extent of the political fallout so far.

The implications of the war for Georgia’s foreign and domestic policy and politics are wide-ranging. The official Georgian response to the war was incongruous: while the Prime Minister, Irakli Gharibashvili, flatly stated Georgia would not join the West in sanctioning Russia, the President, Salome Zourabishvili, went on a media and diplomatic blitz in Europe voicing strong support for Ukraine.

In contrast to the government’s response to the war, the public’s response was clear. Georgians have been rallying in support of Ukraine in city, town, and village.

In light of the war in Ukraine and the surrounding upheaval in Georgia, CRRC Georgia conducted a survey between 7–10 March which included 1,092 respondents. The results lead to a range of conclusions around who Georgians blame for the war (Russia), what Georgians want the government to do (support Ukraine), and the domestic political fallout of the government’s response (Georgian Dream has lost significant support).

Georgians blame Russia for the war

The vast majority of the Georgian public places responsibility for the war on Russia (43%) or Vladimer Putin (37%). Other responses were named by 3% or less of the public, aside from uncertain responses (9%).

The public was also asked about Russia’s motivation for the war. The data indicates that most people believe that Russia started the war to conquer territory (34%) or Ukraine specifically (25%), to revive the Soviet Union (20%), and to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO (17%). Other responses were named by less than 10% of people.

The public wants the Georgian Government to support Ukraine

The survey asked respondents whether they think the Government of Georgia should support the Government of Ukraine more, at its current level, a bit less than at present, or not at all. A large majority of the public reported that they should support Ukraine more (61%) or at current levels (32%). Only 2% said less than at current levels and 1% not at all.

Aside from the above, respondents were asked whether a number of different actions would be acceptable or unacceptable for the Government to take in response to the crisis.

The vast majority of Georgians support supplying humanitarian aid to Ukraine (97%), accepting Ukrainian refugees (96%), and providing financial assistance to Ukraine (91%).

Two-thirds of people (66%) support allowing Georgian volunteers to travel to Ukraine, something the government has attempted to block.

Around half (52%) would support the Georgian government arming Ukraine.

The public wants Georgia to participate in sanctions

The public wants sanctions against Russia to be stronger, and a majority want Georgia to join them. This stands in stark contrast to Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili’s rejection of sanctions.

The survey asked whether the public thought the countries which have imposed sanctions on Russia should strengthen them, keep them at current levels, lighten them, or not sanction Russia at all.

The results show that a large majority think that sanctions should either be strengthened (71%) or remain at current levels (10%). Only 4% think the sanctions should be lightened, and 3% think they should be removed entirely.

When asked whether the Government of Georgia should join in the sanctions, a majority agreed with this view (66%). Views were split on whether Georgia should participate in all sanctions (39%) or some of the sanctions (27%). Only 19% reported that Georgia should not participate in the sanctions at all. A further 14% were uncertain on this issue.

Georgia and Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic Future

In light of Russia’s invasion, Ukraine applied for membership in the European Union, a move quickly followed by Georgia and Moldova.

Public opinion strongly supports Georgia and Ukraine’s application to candidate status. At the same time, there has been little movement in terms of overall support for Georgia’s membership in the EU and NATO (which was already high) since the start of the war.

Respondents to the survey were asked how strongly they supported or did not support Ukraine and Georgia becoming candidates in the European Union. The data indicates strong support from the Georgian public for both countries becoming candidates in the European Union.

Respondents on the survey were asked how strongly they support Georgia’s integration with the European Union, NATO, and the Russian-led Eurasian Customs Union.

Data from the 2020 Caucasus Barometer survey using the same question wording and answer options found that 73% of Georgians supported EU membership and 71% supported NATO membership. Today, 75% support EU membership and 70% support NATO membership, statistically indistinguishable shares from the 2020 data.

The president and prime minister’s performance on the war

The Prime Minister of Georgia, Irakli Gharibashvili, has received significant criticism for his response to the war. While large swaths of the world imposed sanctions on Russia, Gharibashvili firmly stated that Georgia would not participate in the sanctions. Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, even tweeted a thank you to the Georgian public for its support, while slighting the Georgian government for its lack thereof.

In contrast to the Prime Minister, the President of Georgia, Salome Zourabishvili, has received broad praise for her performance in relation to the conflict. Zourabishvili expressed clear support for Ukraine in the conflict and travelled throughout Europe on a media and diplomatic tour in support of Ukraine.

Given the above, it is perhaps unsurprising that the public is significantly more approving of the president’s performance in relation to the war than of the prime minister’s work.

While 64% of the public approved of Zourabishvili’s performance in relation to the war, only 41% approved of Gharibashvili’s performance, a 23 percentage point gap. In contrast, 15% of the public disapproved of Zourabishvili’s performance while 39% disapproved of Gharibashvili’s performance. This leads to a net approval for Zourabishvili of +49% and a net approval rating of +2% for Gharibashvili.

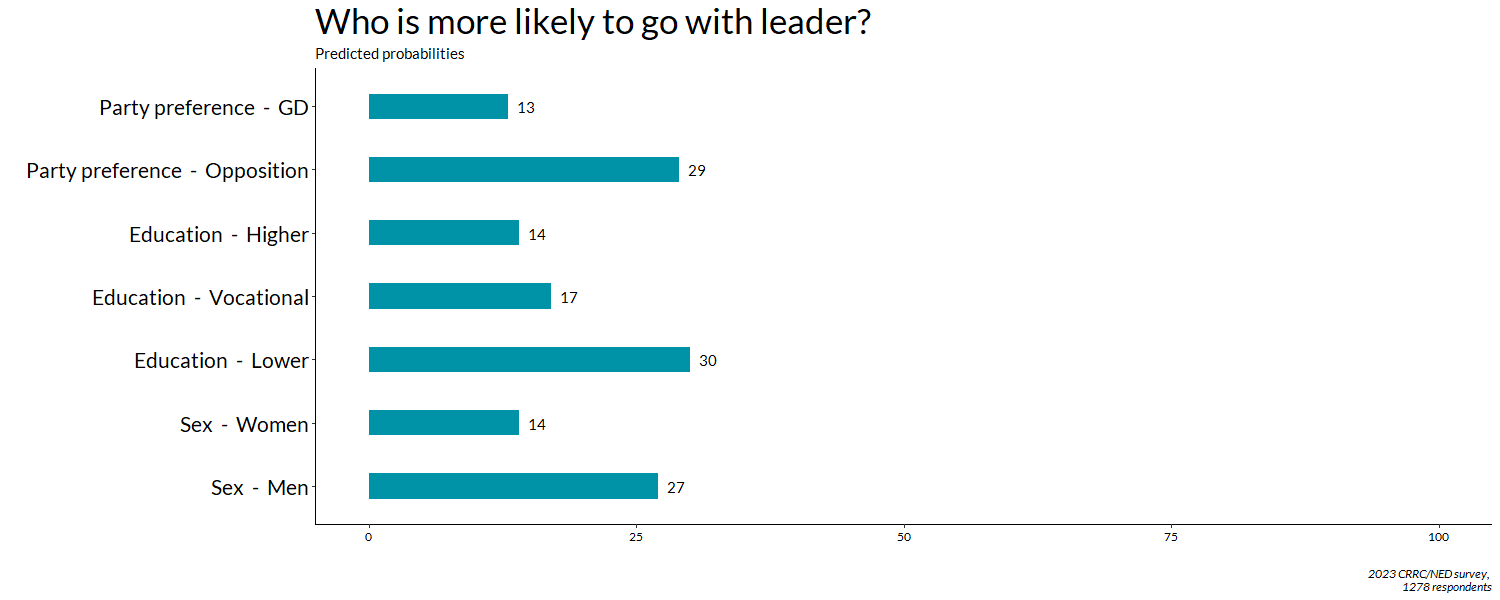

When looking at data broken down by party preferences, the data indicates that Salome Zourabishvili’s performance level being higher than Gharibashvili’s stems from a greater degree of support from the opposition: while 61% of opposition supporters approved of Zourabishvili’s performance in relation to the war, only 32% supported Gharibashvili’s performance. In contrast, Gharibashvili and Zourabishvili had quite similar levels of approval from supporters of Georgian Dream.

The political fallout

With Gharibashvili’s unpopular response to the war, it is unsurprising that Georgian Dream’s base of political support has shrunken.

To identify respondents’ political preferences, the survey asked respondents a) who they would vote for if parliamentary elections were held tomorrow. If the respondent was uncertain, they were asked who they sympathised with compared to other parties.

The data showed a 10 percentage point decline in support for Georgian Dream. At present, 22% of respondents would support Georgian Dream in elections held tomorrow. This compares to 32% of respondents on a January 2022 survey.

That is to say, Georgian Dream has, at least temporarily, lost around a third of its voters.

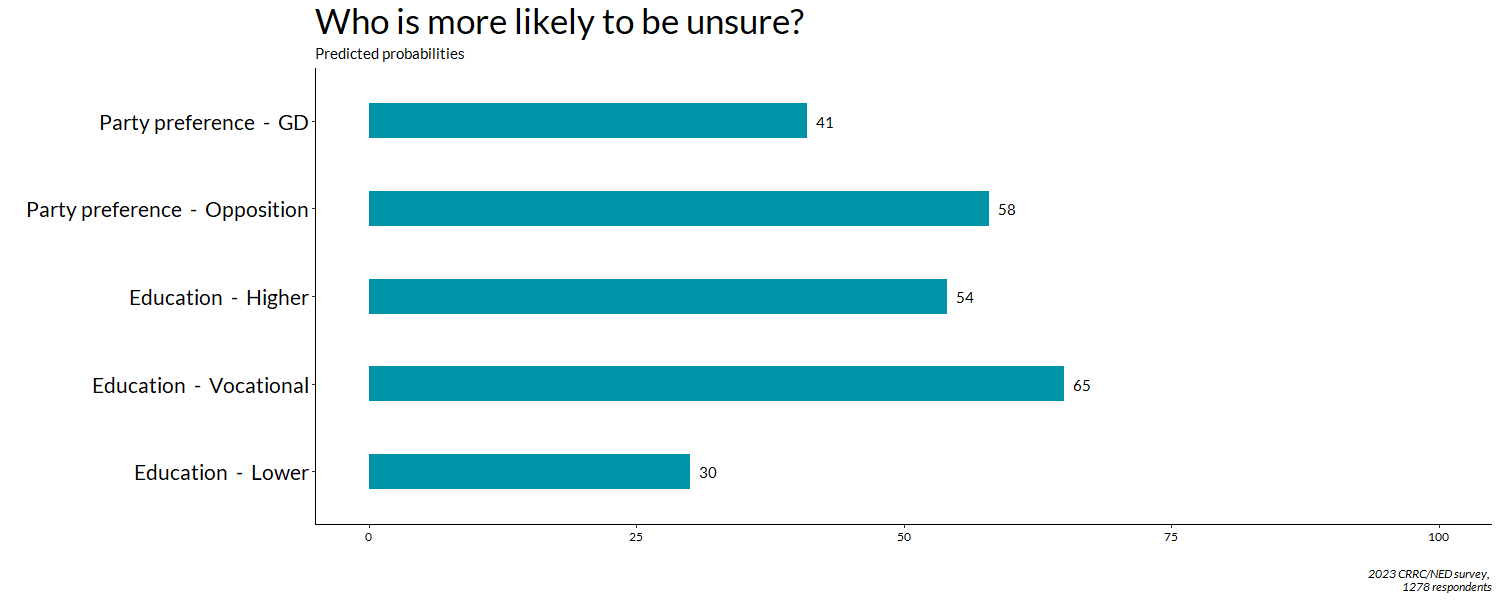

However, it is unclear whether this loss is permanent. The data does not show a gain in support for the opposition relative to January. Rather, the public became increasingly uncertain over who they would support.

On the January 2022 CRRC Omnibus survey, 27% of respondents reported they were uncertain about who they would support in parliamentary elections, while in the March Ukraine survey, 38% of respondents reported the same, a twelve percentage point increase.

The data also shows a slight decline in support for the opposition, with 25% supporting an opposition party in January of 2022, compared with 20% in March.

The remaining respondents refused to answer which party they would support, the share of which shifted within the margin of error between the two surveys (20% in March and 17% in January).

While the official response to Russia’s war has been lackadaisical, the public unambiguously support Ukraine and support doing almost anything to help the country in its fight against Russia. The Georgian public’s views of the country’s Euro-Atlantic future has changed little. However, the public’s view of the government has changed, with Georgian Dream, at least temporarily, losing around a third of its supporters.

The data this article is based on is available here.