Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dustin Gilbreath, a non-resident Senior Fellow at CRRC-Georgia.The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of NDI, CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

In the face of conflicting narratives about the causes of the war in Ukraine, most Georgians see Russia and Putin as responsible for the conflict, but a substantial minority lay the blame with the West. Since Russia invaded Ukraine slightly over a year ago, a war of words has erupted over who is to blame for the war, with the general consensus being that Russia needlessly invaded Ukraine.

In contrast to this consensus, the Russian government has spread propaganda blaming Ukraine for the war, accusing the country’s Jewish president of being a Nazi and stating that the country needed to be ‘de-Nazified’.

Against this backdrop, and in light of Georgia’s history with Russia, what does the Georgian public think?

Data from CRRC-Georgia and the National Democratic Institute’s regular polling in Georgia suggests that most blame Russia as a whole, but an increasing proportion of the public blames Vladimir Putin specifically for the war. And while the majority of the public report that the war is Russia or Putin’s fault, one in six Georgians report that some Western actor is at fault for the war, while one in twelve blame Ukraine.

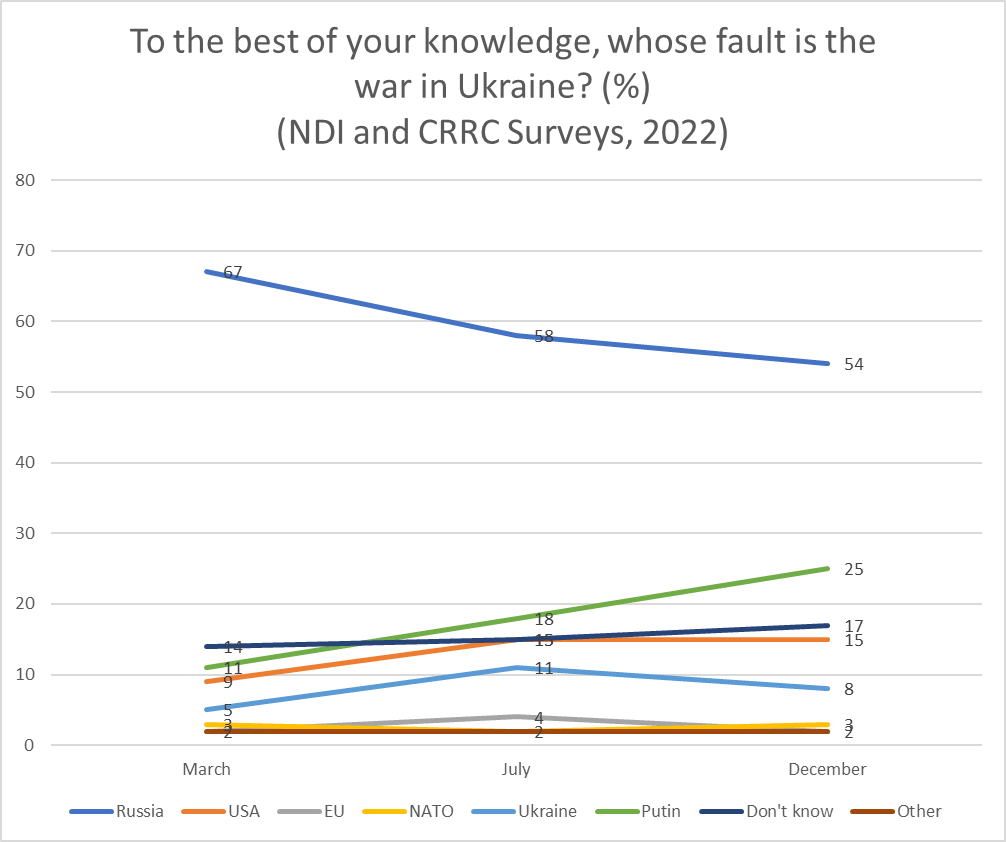

The share of Georgians blaming Russia and Putin for the war shifted in the year following the war, with the share blaming Russia declining from 67% in March of 2022, to 54% in December of 2022. There was a simultaneous rise in the share blaming Putin specifically, from 11% in March 2022 to 25% in December of that year.

A smaller but substantial proportion of the public considers the West to be responsible for the war in Ukraine. While relatively small shares blame NATO (2-3%) and the European Union (2-4%), a relatively high percentage blame the US. One in eleven (9%) blamed the United States in March, which rose to and stayed at 15% in July and December respectively.

Similarly, relatively few Georgians blame Ukraine for the war. This share stood at 5% in March 2022, rose to 11% in July 2022, and then moved to between these shares at 8% as of December 2022.

The remainder of the public is either uncertain about who to blame for the war (14-17%) or names some other factor (2%).

It is important to note that respondents could name up to three responses. Therefore, the shares do not necessarily sum to 100% on the chart above. In the first wave of the survey, Vladimir Putin was not specifically asked about, but respondents still named him. In subsequent waves of the survey, Vladimir Putin was added as a response option.

In the most recent wave of the survey, 59% of the public named only Russia or Vladimir Putin as responsible for the war. One in nine (11%) suggested that only Western actors were at fault for the war. A further 7% named at least one Western actor and one Russian actor. The remainder were mostly either uncertain on how to respond (15%) or refused to answer (1%). Other respondents blamed Ukraine as well as some combination of Russian and Western actors.

Who blames who?

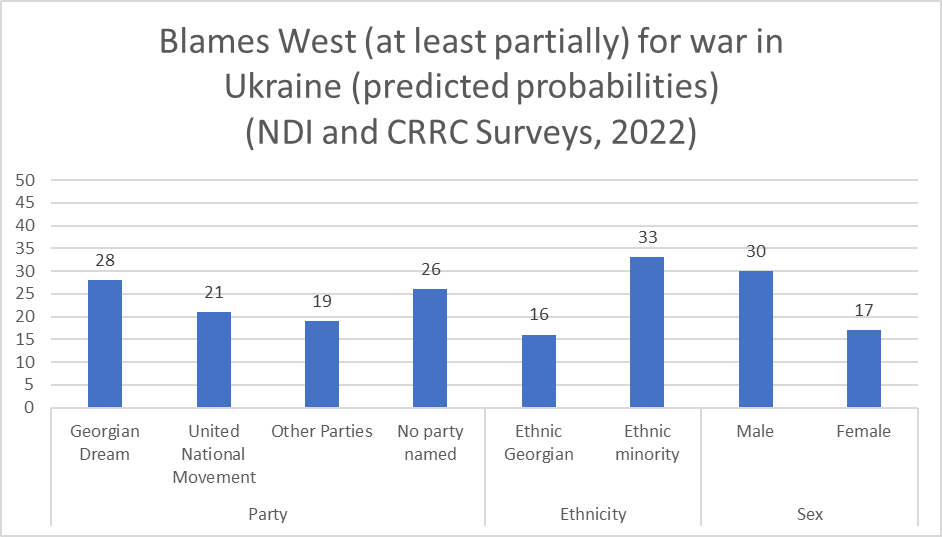

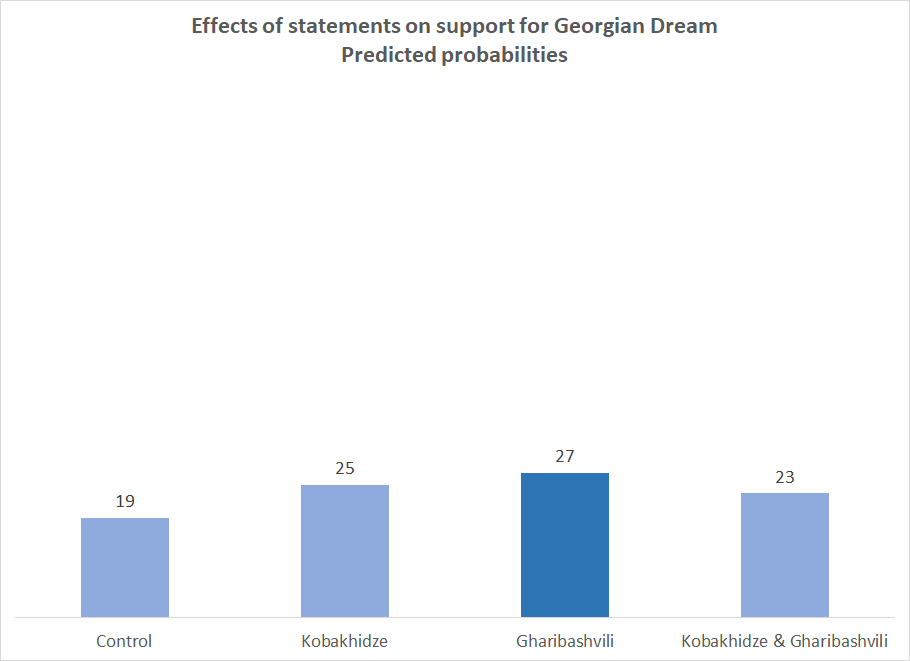

The data suggest that men, people belonging to ethnic minorities, and Georgian Dream supporters are more likely to consider the West (including the US, EU, and NATO) at least somewhat responsible for the war, than are women, ethnic Georgians, and those that do not support Georgian Dream.Ethnic Georgians, opposition supporters, those that claim they support no particular party, and people living in urban areas are more likely to blame Russia and/or Putin, compared to ethnic minorities, Georgian Dream supporters, and people in rural areas.

Ethnic Georgians, opposition supporters, those that claim they support no particular party, and people living in urban areas are more likely to blame Russia and/or Putin, compared to ethnic minorities, Georgian Dream supporters, and people in rural areas.

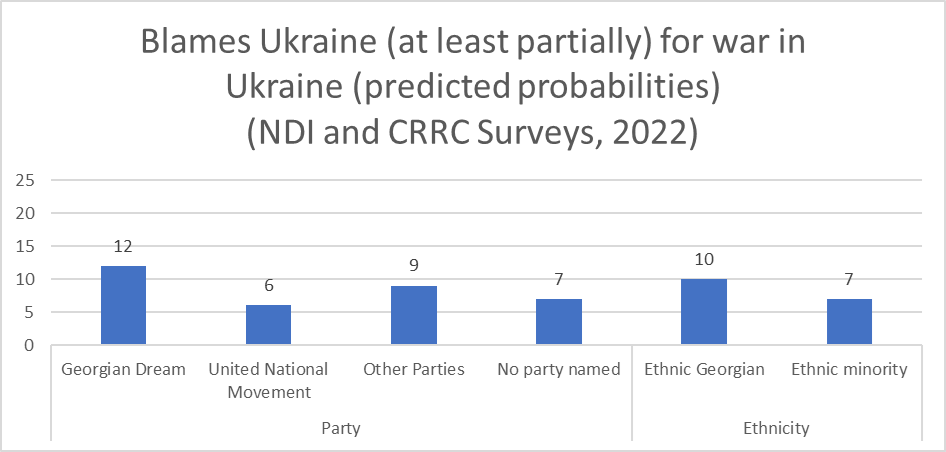

Men and Georgian Dream supporters are more likely to believe that Ukraine is at fault for the war than women and opposition supporters.

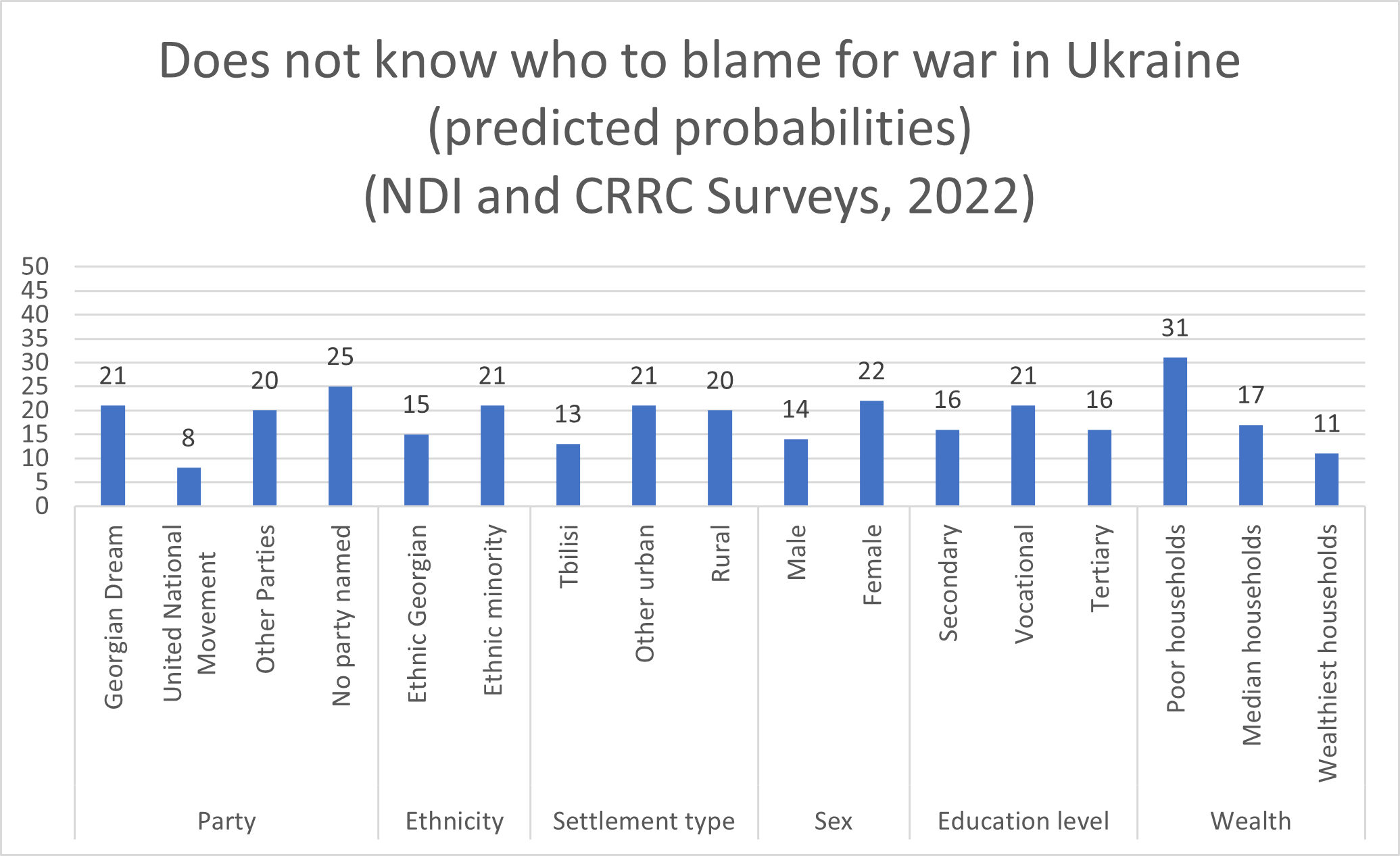

Women, people with vocational education, those outside Tbilisi, poorer people, and people who support Georgian Dream are more likely than men, people with secondary education, those in Tbilisi, wealthier people, and those who support the opposition to be uncertain about the causes of the war.

The data do not suggest that any particular group is more or less likely to name at least one Russian actor and one Western actor for the war.

While Russia’s fault in the war is questioned by relatively few in Georgia, the data do show that some groups are more likely than others to believe that Western actors or Ukraine itself is partially or fully at fault. A substantial share also remains uncertain.

Note: The social and demographic breakdowns shown in the article above were generated from a regression analysis. The analysis had someone’s belief about who was at fault for the war as the dependent variable, including naming Russia/Putin or not, naming any Western institution or not, naming both a Western and a Russian actor or not, and naming Ukraine or not. The independent variables included age group (18-34, 35-54, 55+), sex (male or female), settlement type (Tbilisi, other urban, or rural), education level (secondary, vocational, tertiary), wealth (an index of durable goods owned by the respondents’ household), ethnicity (ethnic minority or ethnic Georgian), employment (working, unemployed, or outside the labor force), and party support (Georgian Dream, United National Movement, other opposition, refuse to answer/don’t know/no party). This article only reports on statistically significant differences between groups.