Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. This article was written by Eto Gagunashvili, a researcher at CRRC Georgia. The views presented in this article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia.

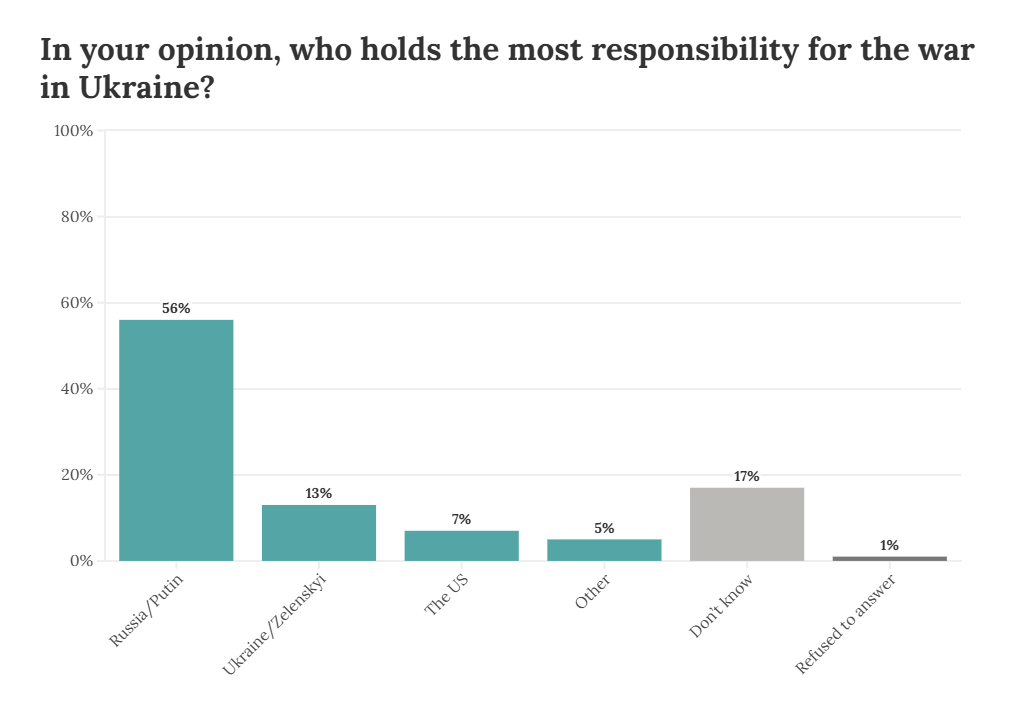

While over half of all Georgians believe that Russia or Russian President Vladimir Putin holds the most responsibility for the full-scale war in Ukraine, a large minority, 17%, felt they were uncertain who to blame, while another 13% considered Ukraine or its president Volodymyr Zelenskyi personally responsible.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has shaped global politics since its start. Past polling has shown that the public in Georgia, a country with its own territorial conflicts with Russia, has broadly supported Ukraine. Data from CRRC Georgia’s Caucasus Barometer survey from Spring 2024 suggests that most people in Georgia hold Putin and Russia responsible for the war.

The data shows that most Georgians (57%) believe that Russia or Putin holds the most responsibility for the war in Ukraine. Just one in eight Georgians (13%) considered Ukraine or Zelenskyi personally responsible.

However, notably, 17% of Georgians were uncertain and reported that they did not know who holds the most responsibility for this war.

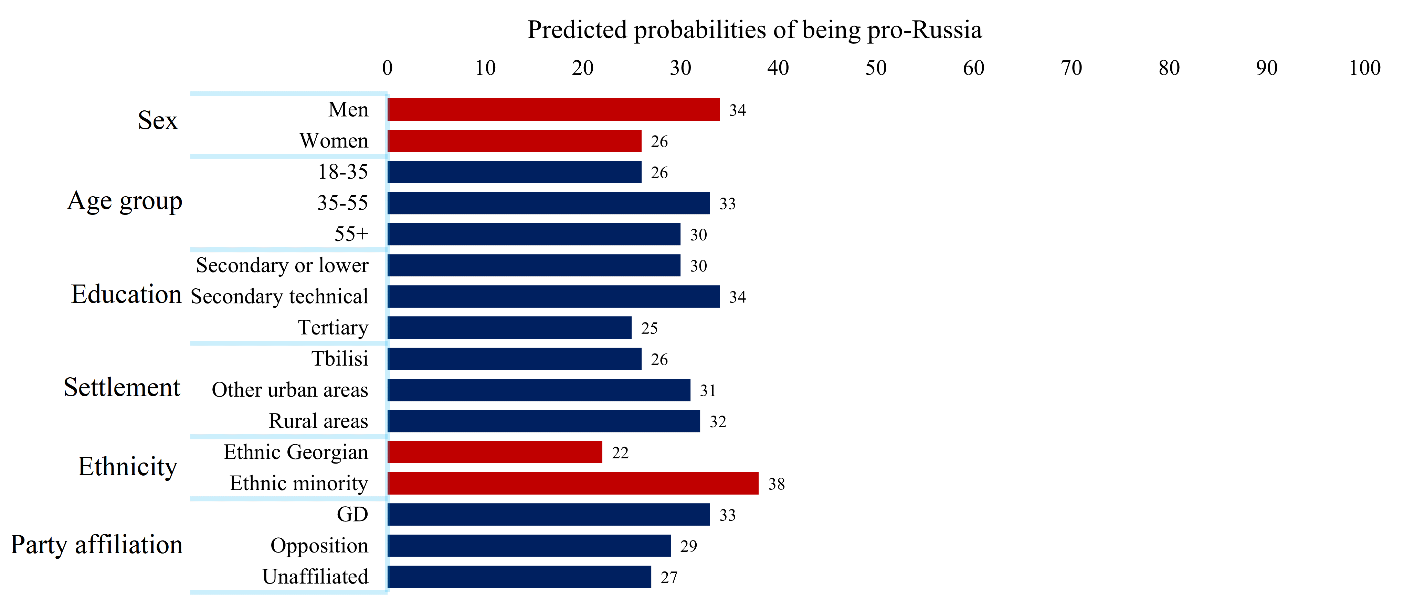

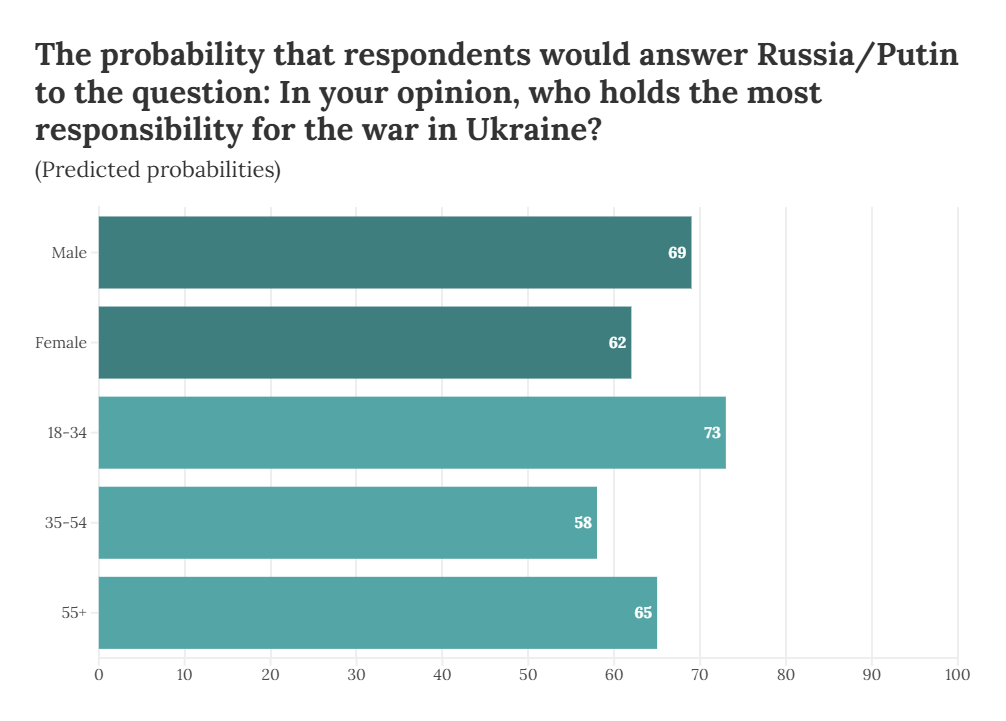

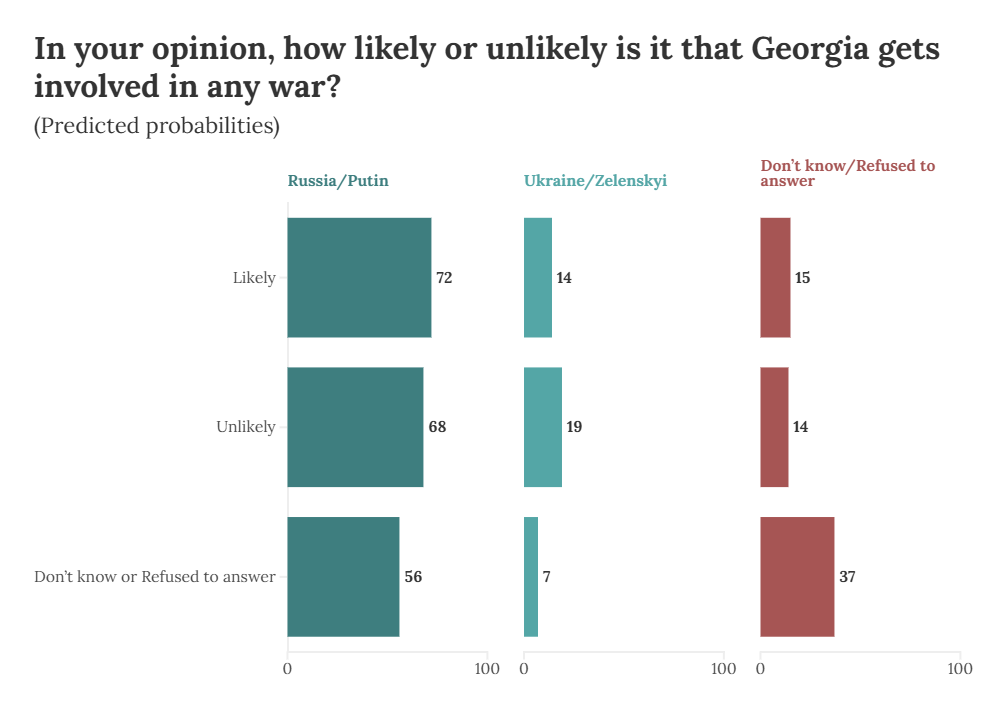

Further analysis showed that beliefs about responsibility for the war in Ukraine were associated with age, political preferences, and perceptions of the likelihood of Georgia’s involvement in any war.

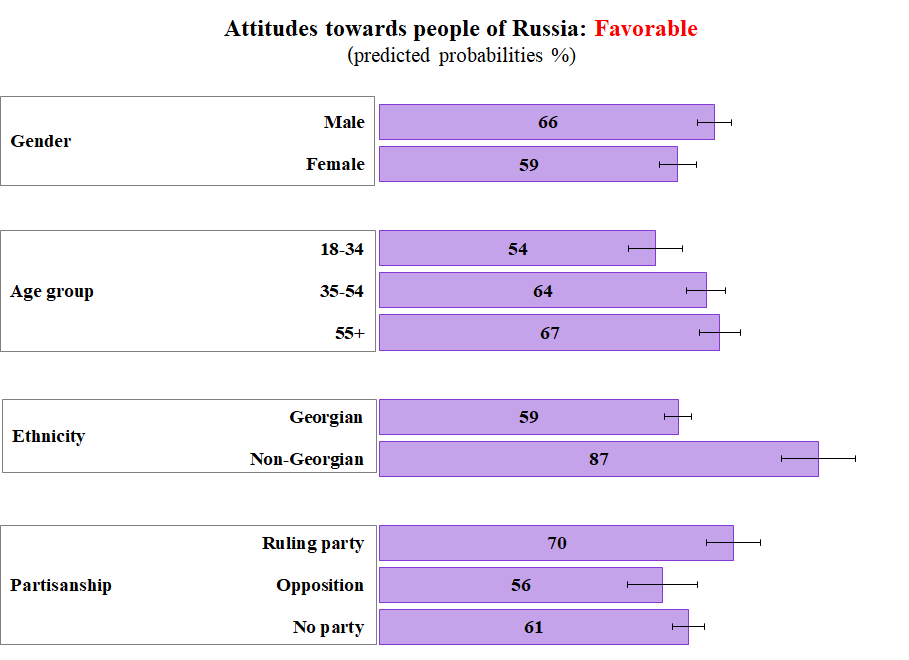

For example, respondents aged 35 and older were less likely to blame Russia or Putin compared to younger respondents aged 18–34.

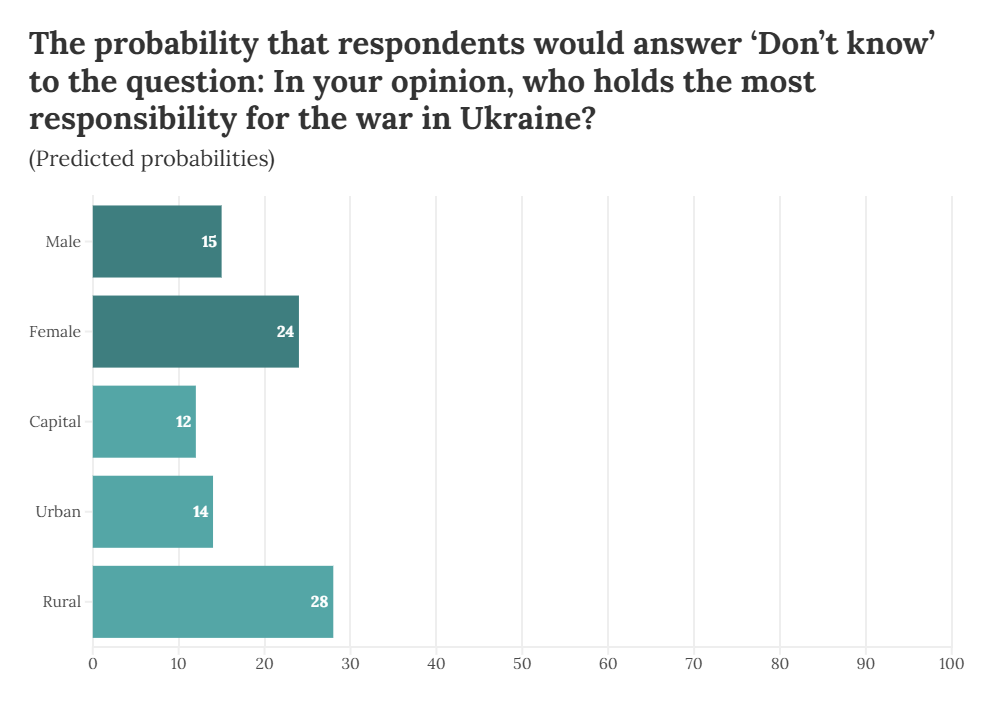

In turn, women were nine percentage points more likely to report uncertainty, selecting ‘don’t know’ when asked about responsibility for the war in Ukraine, while people living in rural areas were 16 percentage points more likely to be undecided on the issue.

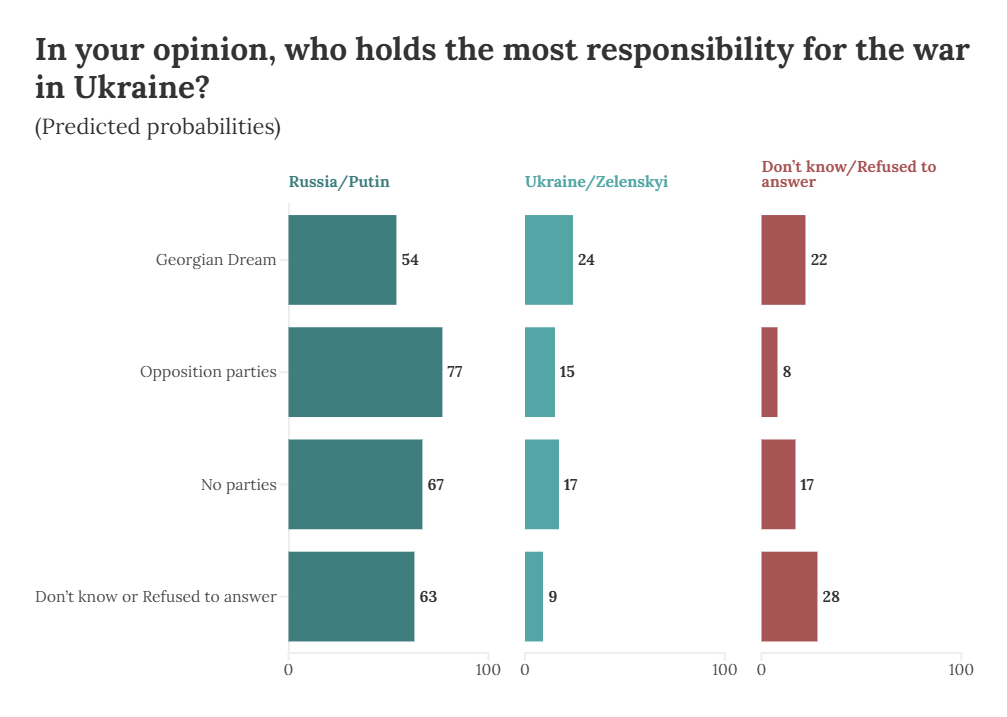

Opposition party supporters were 23 percentage points more likely to blame Russia/Putin than those who supported the ruling Georgian Dream party. They were also 14 percentage points less likely to be undecided about responsibility for the war in Ukraine compared to ruling party supporters.

Respondents who did not provide a party preference on the survey were 15 percentage points less likely to place blame on Zelenskyi or Ukraine compared to Georgian Dream supporters.

Respondents who were uncertain about the risk of Georgia’s involvement in any conflict were significantly less likely to blame either Ukraine/Zelenskyi or Russia/Putin, and were more likely to be undecided.

Most Georgians, particularly the younger generation and opposition party supporters, hold Russia or Putin responsible for the war in Ukraine. Women and people living in rural areas were more likely to be undecided. Those who were uncertain about Georgia’s potential involvement in war also tended to be undecided about who is to blame for the war.

This analysis is based on a multinomial logistic regression, where the dependent variable is ‘Who holds the most responsibility for the war in Ukraine?’ with three answer options: Russia/Putin, Ukraine/Zelenskyi, and Don’t know. The independent variables include gender, age, settlement type, education, ethnicity, employment, partisanship, and the perceived likelihood of Georgia’s involvement in any war.