Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Salome Dolidze and Kristine Vacharadze. The views expressed in the article are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

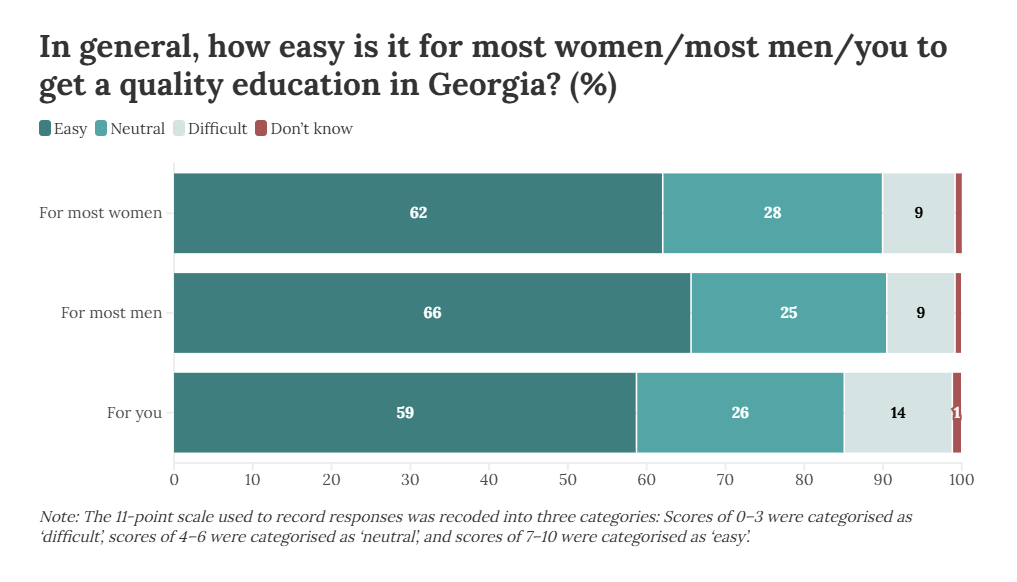

A newly released UN Women and CRRC Georgia report has found that the majority of Georgians believe access to quality education is equal between men and women, and that such an education is relatively easy to obtain.

According to a 2021 Pew Research Centre report, young women are more likely than men to attend college, a trend that is consistent across the globe.

This trend is also observed in Georgia, where the proportion of female students is higher than that of male students — according to official statistics, in the 2024–2025 school year, 53% of university students were female and 47% male.

Despite the statistics, according to data gathered by UN Women and CRRC Georgia, most Georgians believe access to quality education is fairly equitable between genders, though opinions vary slightly when it comes to men’s versus women’s access.

According to the new UN Women and CRRC Georgia report, 62% of the Georgian population agree that it is easy for women to receive a quality education. A slightly larger share (66%) believe that the same is true for men. Fewer (59%) think that a quality education is easily accessible to them in Georgia.

Regarding the question of how easy it is to access quality education in Georgia, regression analyses show that younger people (16–24), those who are employed, and individuals with at least some higher education are more likely to perceive access to quality education for themselves in Georgia as easy compared to older individuals, the unemployed, and those with lower levels of education. This perception did not vary by gender, settlement type, or ethnicity, controlling for other factors.

Opinions on men’s and women’s access to education in Georgia vary. People who are not working and those aged 35–44 are less likely to perceive women’s access to quality education as easy, compared to employed individuals and younger age groups. This attitude does not vary by education level, gender, settlement type, or ethnicity, all else equal.

Similarly, demographic factors such as employment status, ethnicity, and settlement type predict perceptions of men’s access to education. Ethnic minorities, people in urban areas, and employed individuals are more likely to perceive men’s access to quality education as relatively easy, compared to ethnic Georgians, residents of the capital, and those who are not employed.

The vast majority (88%) of the population disagrees with the statement that it is more important for a boy to obtain a university education than a girl. The perceived social norms are similar to personal attitudes, though there is greater uncertainty over what the social norm is.

One in seven (15%) believe that the majority of people in their community think education is more important for boys than girls. A similar share is uncertain, and 69% disagree. A regression model does not indicate any statistically significant differences between demographic groups on these questions.

The prevailing belief among the population of Georgia is that access to quality education is equal and relatively easy to obtain for the majority of men and women, as well as for themselves. The findings suggest that while most Georgians believe there is equal access to quality education for men and women, subtle differences in perceptions exist across demographics. Social norms largely support gender equality in education, with a small minority feeling that boys’ education is more valued.

The data used in this article is available here. The regression analysis used in this article included the following variables: age (16-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55+); Sex (male or female); settlement type (Tbilisi, other urban, rural); education level (secondary or lower, vocational, completed or uncompleted higher education); ethnicity (ethnic Georgian or ethnic minority); and employment status (employed or unemployed).