Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Nino Zubashvili, a Researcher at CRRC-Georgia, The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

Across various demographic groups, Georgians are uncertain about what their economic futures might hold, with those from lower-income backgrounds more uncertain than those with a higher income.

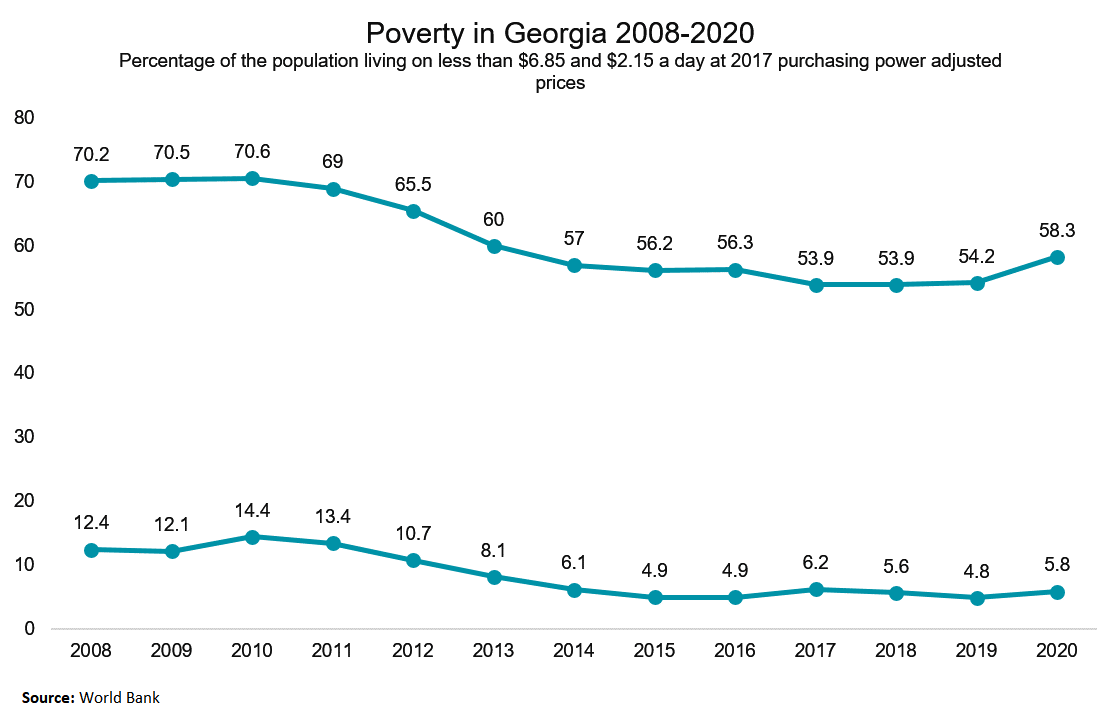

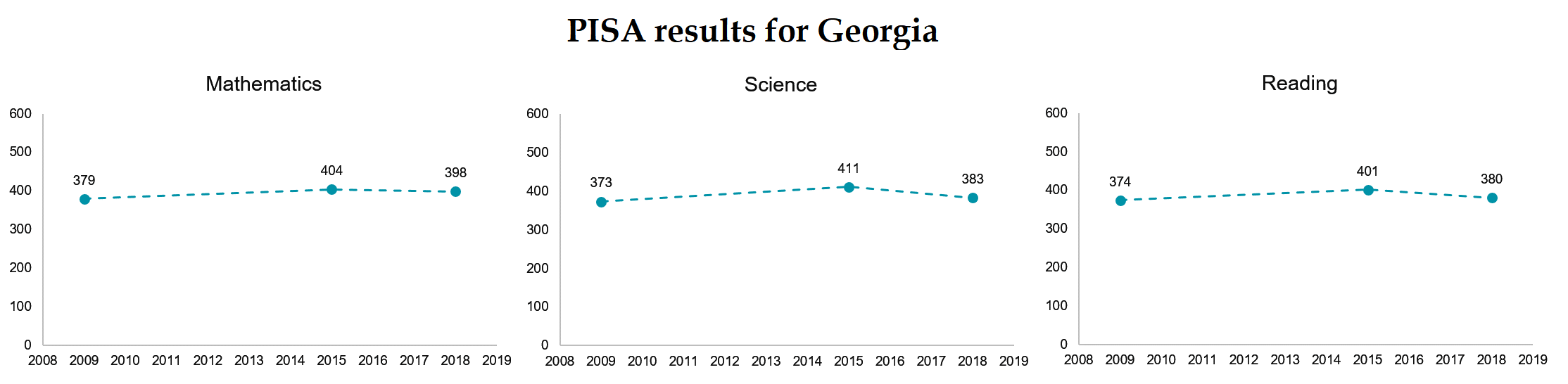

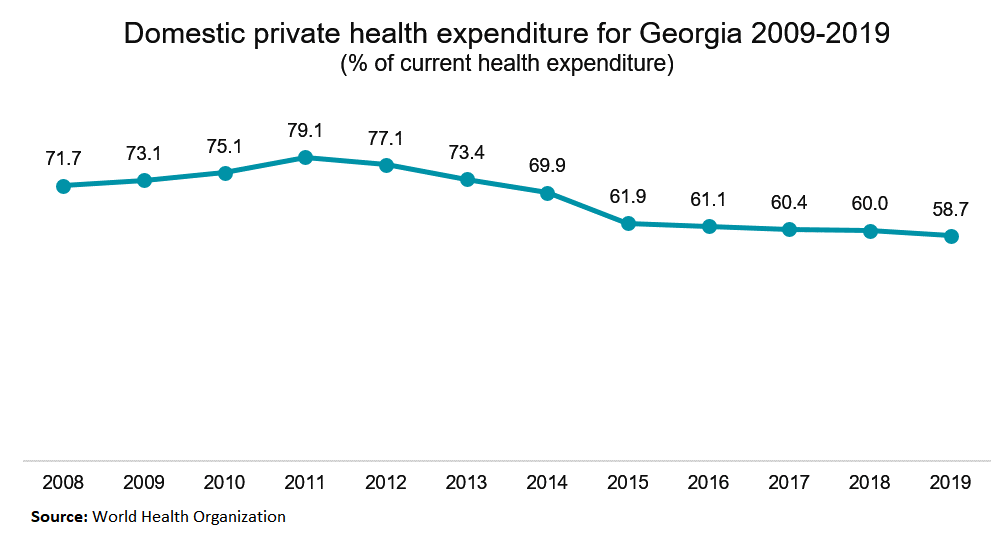

Georgia today faces numerous structural challenges that hinder social and economic development, such as low productivity and low-quality jobs, poor quality of education, poor links between education and employment, high unemployment, and poverty.

On top of this, high use of the dollar alongside the country’s own currency, and reliance on income from tourism make the country vulnerable to external shocks.

Despite some positive developments, including becoming an upper middle income country in 2016, a ‘very high’ rating on the Human Development Index, and a low average multidimensional poverty score (37%), public opinion polling has found that the public is highly uncertain about their economic prospects.

CRRC Georgia’s Caucasus Barometer 2021 data shows that while a plurality of the population feel they are part of the middle class, almost half are uncertain about their households’ future economic well-being.

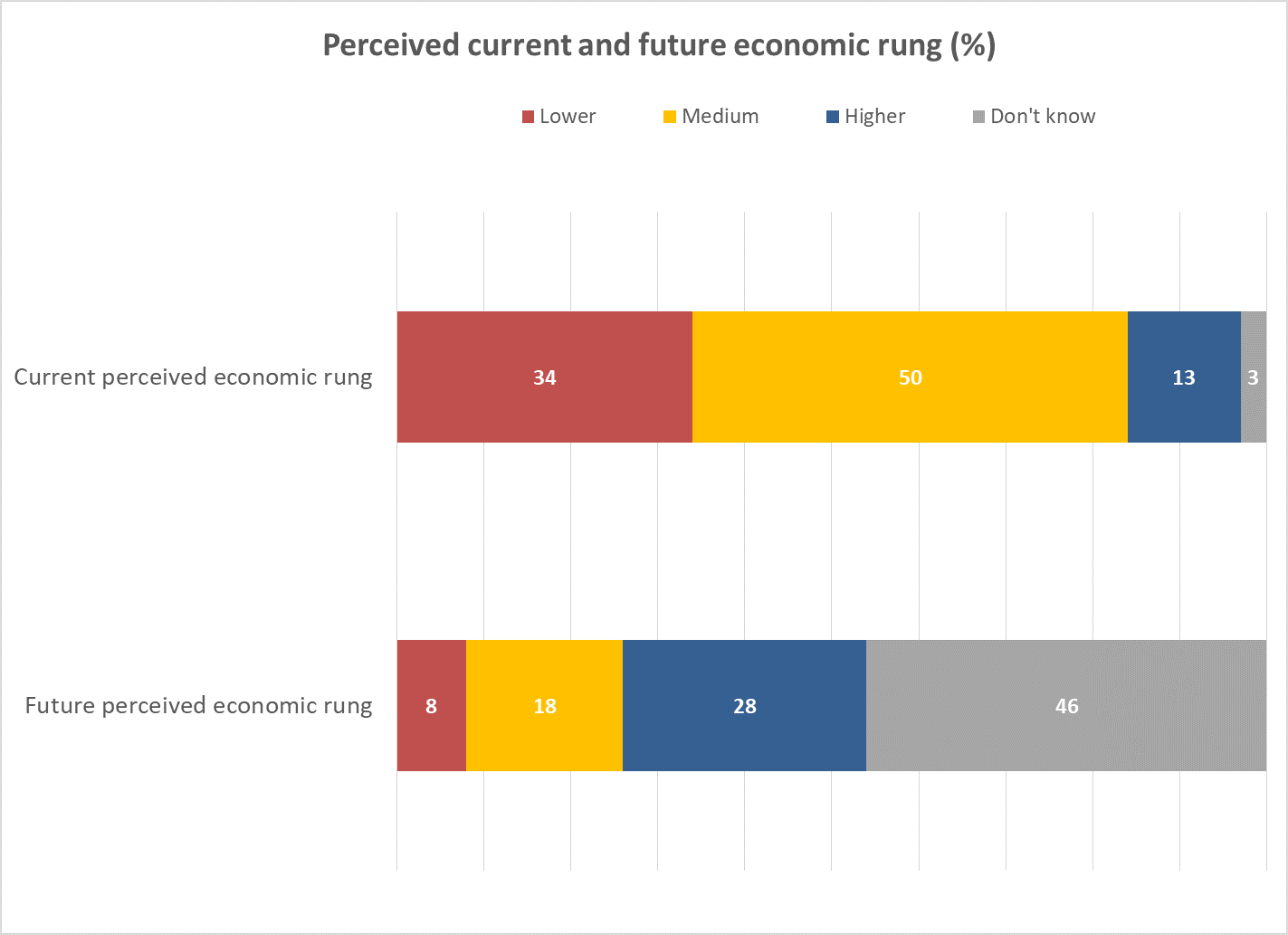

Half (50%) of Georgia’s population perceive their current economic status as in the middle, 34% as poor, and only 13% as high.

When asked what they expect their economic status to be five years in the future, 8% of the population see themselves on the lower rungs of the economic ladder, with 18% seeing themselves in the middle class. Notably, 28% believe they will be relatively well off, twice as many as currently see themselves in that category.

But uncertainty about the future is substantial. Almost half of the public (46%) answered that they didn’t know what their household’s economic status would be in five years.

Numerous factors are associated with how people in Georgia perceive their future economic rung.

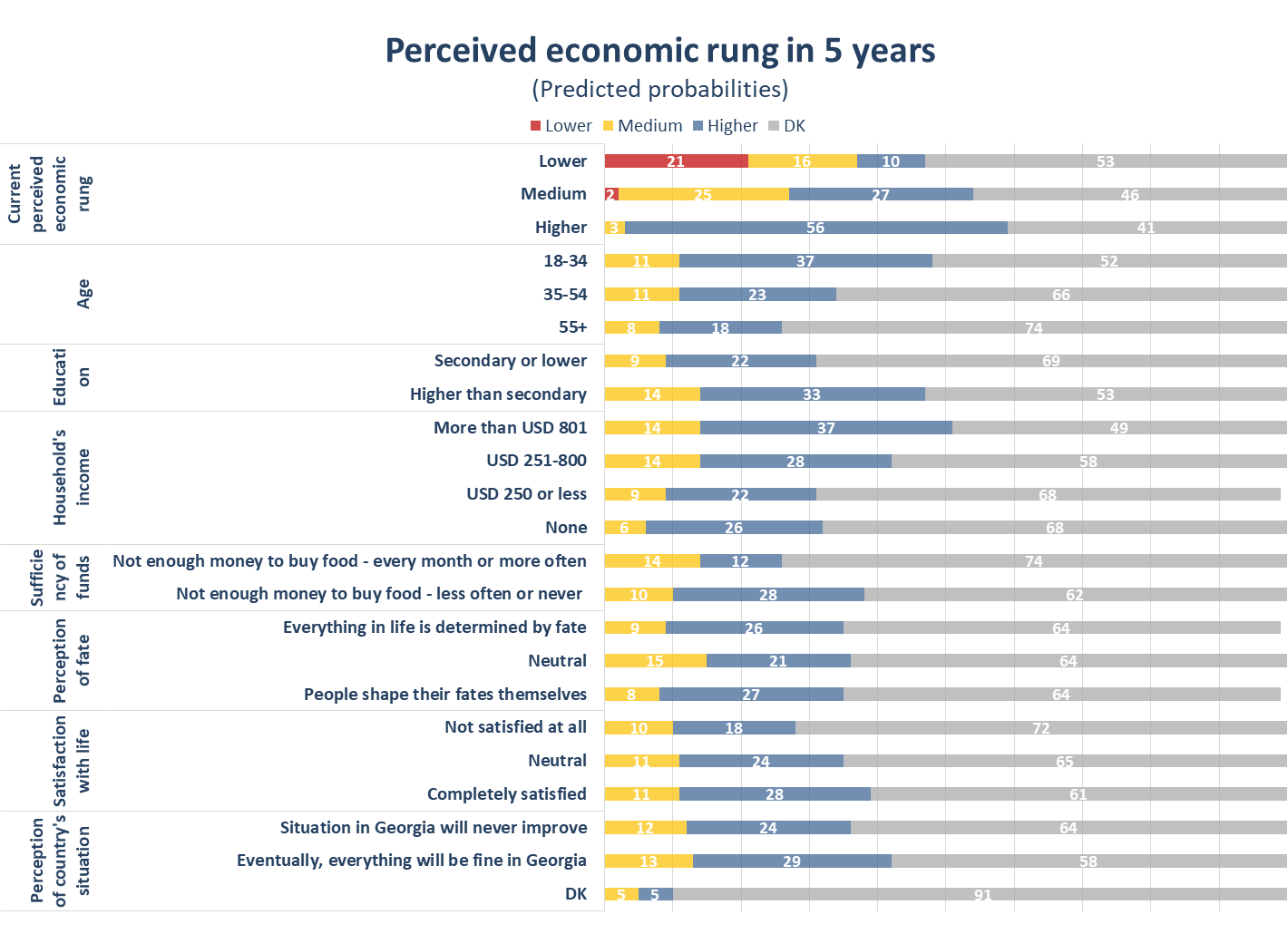

More than half of those who perceive themselves to be on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder are uncertain about the future. A fifth on the lower rungs expect to stay there, and around a fifth expect to move to the middle of the ladder. Few on the lowest rungs today expect to move to a relatively well-off rung.

In contrast, wealthier people, as measured along a wide range of variables, tend to expect a better future for themselves. People who perceive themselves to be relatively well-off have less uncertainty about their economic futures, and expect to continue to be relatively well-off.

Similar patterns are present for people and households with higher measured incomes, and who do not struggle to buy food.

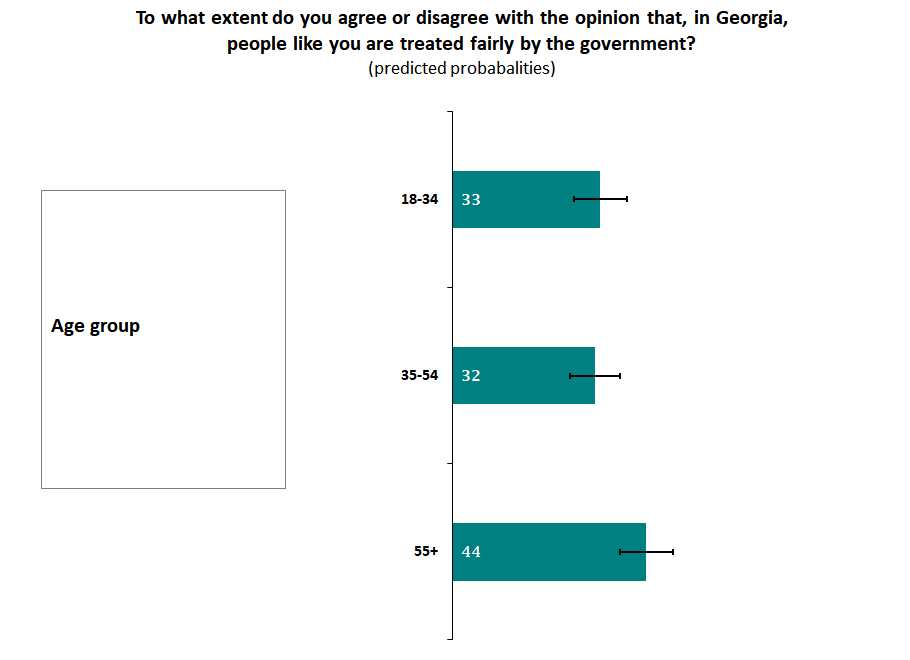

In terms of age, younger Georgians (aged 18-34) have higher expectations for a better economic future and less uncertainty compared to other age groups. With age, expectations for a better economic future decrease, and uncertainty increases.

Economic expectations are also notably higher and uncertainty notably lower among those with a higher education, compared to those with a lower level of education.

Personal beliefs and perceptions of the country’s future are also associated with a household’s perceived future economic rung. Those who believe that ‘the situation in Georgia will never improve’ are slightly less likely to expect improvements in the economic situation compared to those who believe that everything will be fine in Georgia.

Finally, it is perhaps unsurprising that people who are currently more satisfied with life are also more likely to have positive expectations for their economic futures.

Gender, ethnicity, settlement type, employment, religious denomination, frequency of attendance at religious services, whether or not someone has enough money to buy durable goods or not, ownership of durable goods, party affiliation, whether people think everything in life is determined by fate or not, and generalised trust were not associated with what people think their household’s economic future holds.

The largest share of people in almost every socio-demographic group in Georgia are uncertain about their economic futures, regardless of their level of education, perceptions of fate, or perspective on Georgia’s politics.

Note: The data used in the article can be found on CRRC’s online data analysis tool.

The analysis was carried out using logistic regression. The regression included the following social and demographic variables in all cases: sex (male or female), age group (18–35, 35–55, 55+), ethnic group (ethnic Georgian or other ethnicity), settlement type (capital, other urban, rural), educational attainment (secondary or lower education, or higher education), employment situation (working or not), party support (GD, opposition, no party, DK/RA), current perceived economic rung (low, medium, high), religious denomination (Orthodox Christian, other, none), frequency of attendance to religious services (frequently, sometimes, rarely, never). Household’s economic well-being measurements included household’s income, household’s purchasing power (Money not enough for durables, money enough for durables and more), sufficiency of household’s income (Not enough money to buy food every month or more often, not enough money to buy food less often or never), ownership of durable goods. Attitudinal variables tested as part of the analysis included, whether or not one believes in fate, generalized trust, satisfaction with life, whether politics in Georgia is going in the right or wrong direction, whether the situation in Georgia will improve. Both attitudinal variables and measures of households’ economic well-being were tested independently in separate regression analyses that controlled for the previously mentioned social and demographic variables.