Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dustin Gilbreath, a Non-resident Senior Fellow at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

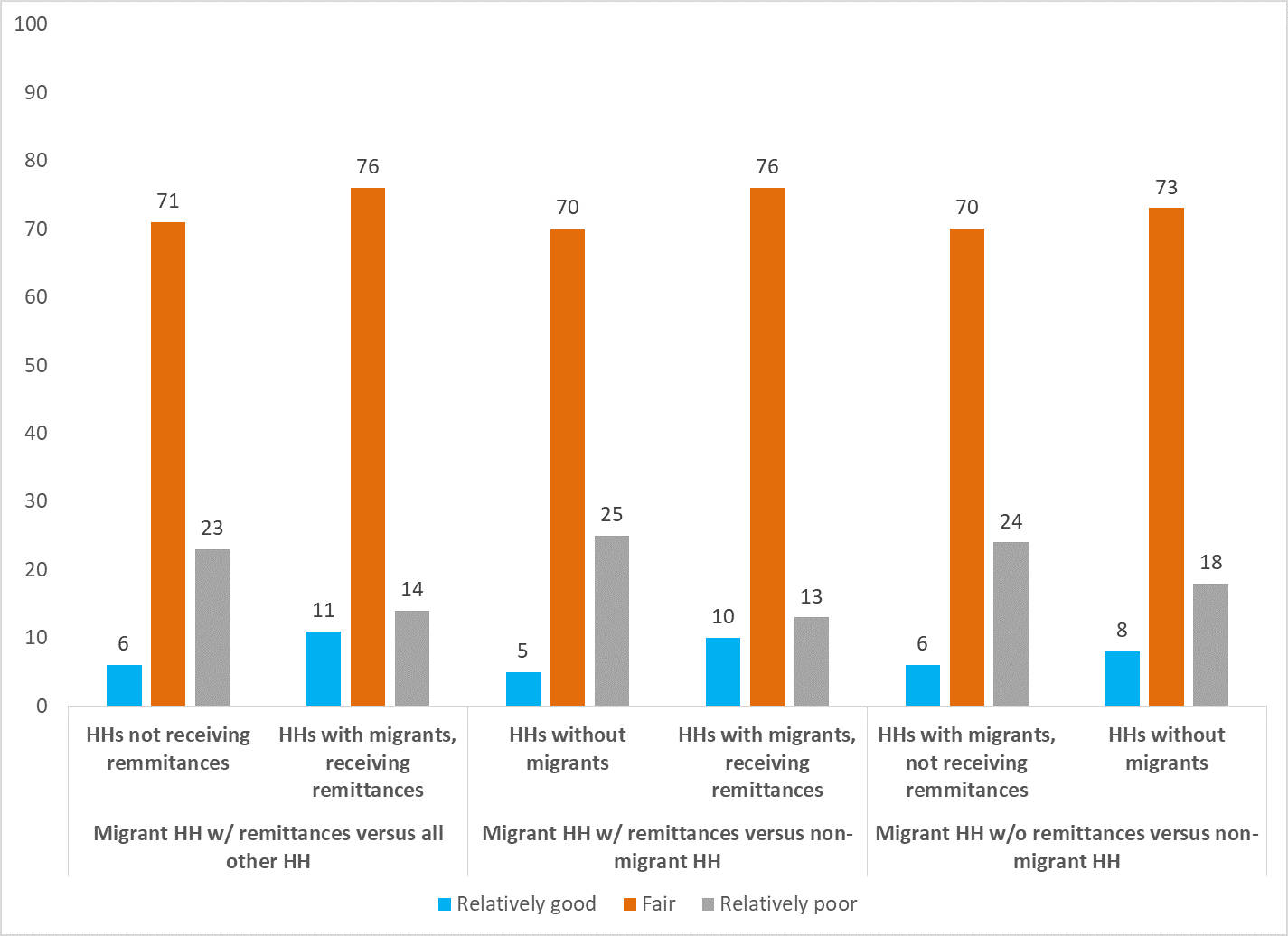

Saying that COVID-19 changed the world is perhaps an understatement. Although a health catastrophe first and foremost, economies also plunged with the emergence of wide-ranging restrictions on activity. World Bank data suggests the global economy shrank between 2019 and 2020 by approximately 3.3%. In Georgia, the corresponding figures were a 6.7% decline in the size of the economy.

As COVID-19 restrictions have been largely removed, the world has witnessed an economic recovery, albeit combined with the highest rate of inflation seen in recent memory. Despite wide-ranging rhetoric around building back better, data from a newly released World Bank study, which CRRC Georgia conducted, suggests that while the economy is recovering, many groups are facing greater barriers to re-entering the workforce.

Since December 2020, CRRC Georgia has been conducting a series of telephone surveys for the World Bank. The results of the survey show a clear rise in the share of the public that is engaged in employment. While 32% of the public (over the age of 18) reported having a job in December 2020, 43% did in March of 2022.

Still, this data indicates that employment has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels, with 51% of the public reporting that they had been employed prior to the pandemic.

While the economy is clearly recovering, the data also show that recovery in employment is unequal.

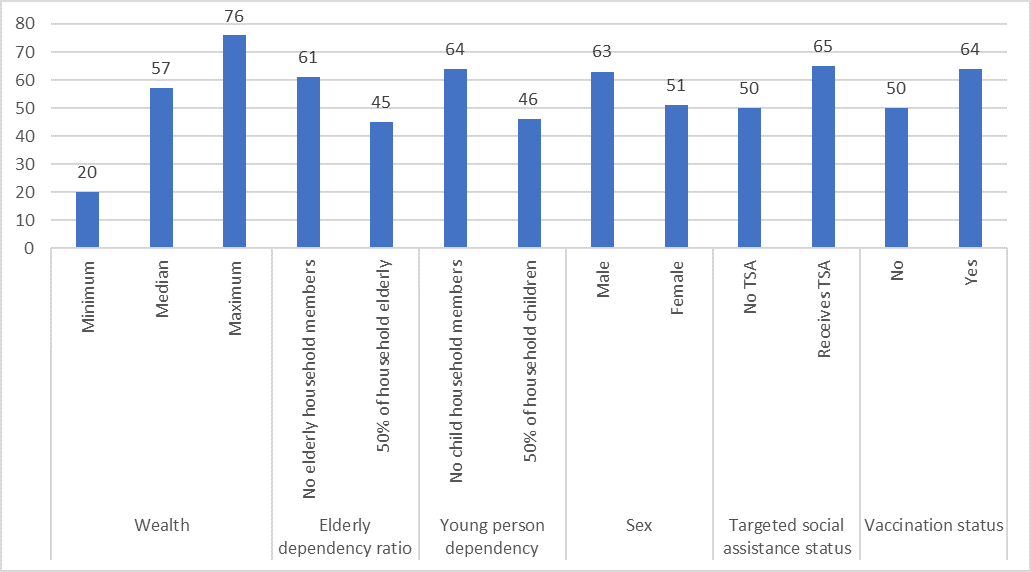

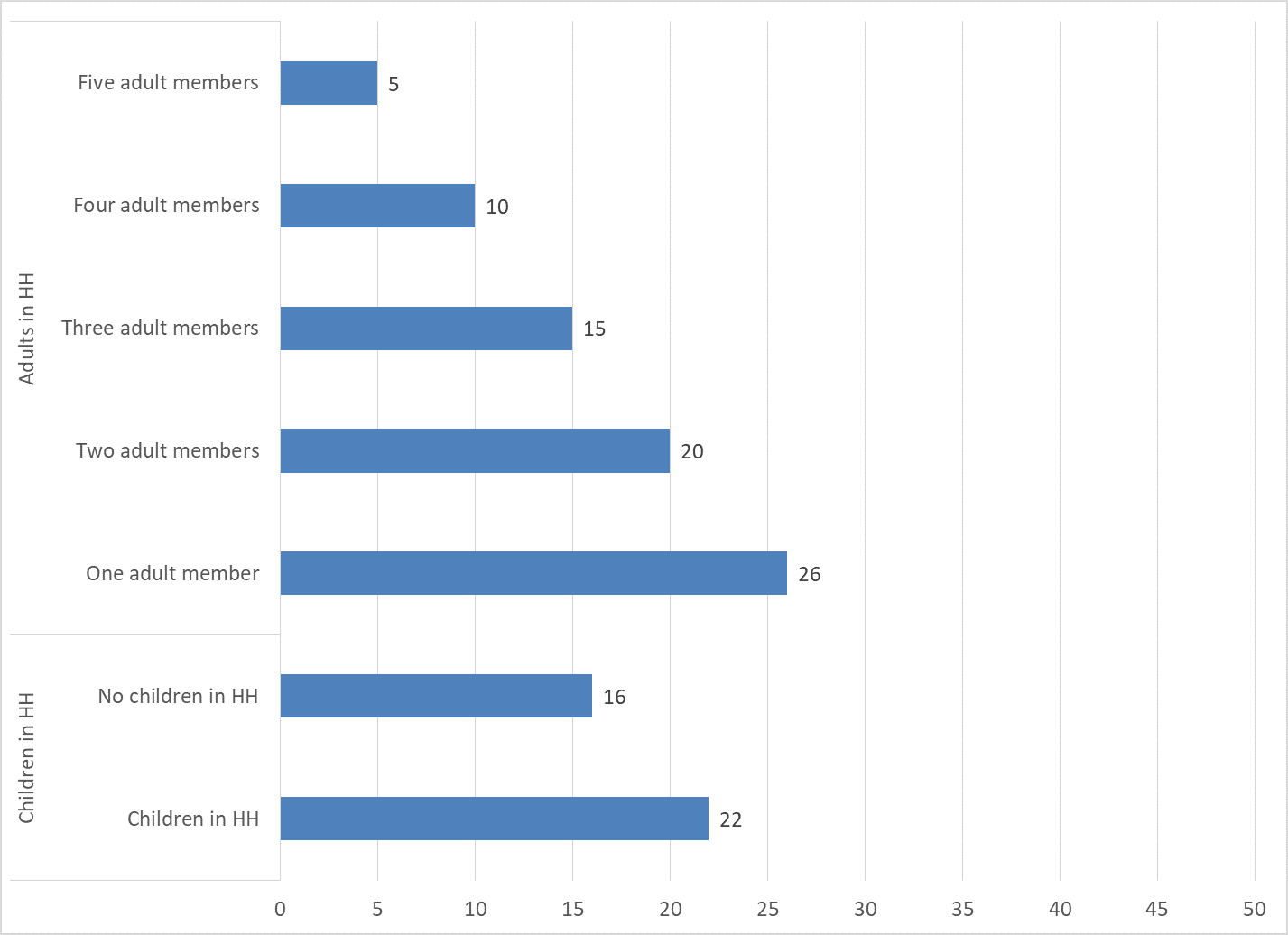

Regression analysis comparing people who lost a job during the pandemic and have not returned to employment to people who lost a job during the pandemic and did return to work suggests that a number of traditionally economically disadvantaged groups face larger challenges in re-entering the workforce.

Women who lost a job during the pandemic are 12 percentage points more likely not to be working at present than men, while people in poor households are substantially less likely to have re-entered the workforce.

In addition, the more elderly people there are in a household, the less likely someone who lost a job during the pandemic is to have returned.

Similarly, in households with relatively large shares of children, people who lost a job during the pandemic are significantly less likely to be working today than in households with fewer children.

People who did not get vaccinated are 14 percentage points less likely to have returned to the workforce than people who did get vaccinated.

In the one bright point in the analysis, people in families that receive targeted social assistance were more likely to return to work than in families that do not receive social assistance.

In contrast, there are no significant differences between age groups, settlement types, households with more and fewer members, people of different education levels, ethnic groups, and people who did and did not catch COVID-19 after controlling for the factors shown in the chart above.

Women, people with greater numbers of elderly people, and greater numbers of children in them all remain less likely to be employed at present than men and people without children or elderly people in the household.

This suggests that domestic work and care work burdens related to the pandemic may be at play in people’s lack of return to the workforce. However, this would require further research to confirm.

In the above context, actors working on Georgia’s economic recovery should look into policies which can support a more equal recovery.

Note: The data this article is based on is available here. The analysis of which groups have and have not returned to the workforce was conducted using a logistic regression which controlled for the following variables: Age (18-34, 35-54, 55+); Sex; Settlement type (Tbilisi, other urban, rural); Household member count; Education level (tertiary or not); Child dependency ratio (share of household 18 or under); Elderly dependency ratio (share of household over the age of 64); Received targeted social assistance aside from an old age pension; Caught COVID 19/ had a family member with COVID 19 or not; Vaccinated against COVID 19 or not; Ethnicity (Ethnic Georgian or ethnic minority); Wealth index (A simple additive index of ownership of a number of durable goods within a household).