A slightly jeering expression in Georgia when speaking about employment prospects suggests that to get a job, you need to know English and how to use computers. Data from Caucasus Barometer 2019 shows there’s a bit of truth in the jest.

Overall, 40% of people on the survey reported having a job. A logistic regression including basic demographic variables, like settlement type, age, gender, minority status and education, suggests that people between the ages of 35 and 54, men, and those with higher education have higher chances of being employed, controlling for other factors. Other demographic factors do not show statistically significant differences.

Aside from the above demographic characteristics, knowledge of English and of computers was also looked at to test the anecdote. People who report knowing English at a basic level or higher are eight percentage points more likely to be employed, controlling for other factors. Knowing how to use a computer at even a basic level has an even larger effect for 19 percentage points, controlling for other factors. The social and demographic characteristics described above remain significant after controlling for knowledge of English.

Note: Two different logistic regression models were used to generate chart above: (a) self-reported employment in relation to the knowledge of English and (b) self-reported employment in relation to the knowledge of computer. The knowledge question were recoded. Options: “Beginner”, “Intermediate”, and “Advanced” were coded as ”Beginner or higher”. “No basic knowledge” stayed the same. The regression model for both cases also included the following demographic co-variates: age; gender; ethnicity, education and settlement type.

In general, these findings align with perceptions of what factors are most important for getting a good job in Georgia. People name education as one of the most important factors for getting a good job in Georgia.

Age, sex, knowledge of English and how to use a computer, and education, are associated with employment in Georgia. This confirms the anecdotal evidence. However knowledge of using a computer in comparison to the knowledge of English appears to be a more important factor for getting a job in Georgia.

To explore more the Caucasus Barometer 2019 survey findings for Georgia, visit CRRC’s Online Data Analysis portal. Replication code for the data analysis is available at CRRC’s GitHub repository here.

Monday, March 23, 2020

Know English and how to use a computer?

Posted by

CRRC

at

8:27 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Employment, English, Georgia

Friday, September 27, 2019

The gender gap in expected wages in Georgia exists only among the well off

[Note: This blog post was originally published in partnership with OC Media, here.]

Much has been made of the gender pay gap in Georgia. A related but different economic indicator is the reserve price of labor i.e. the wage which someone wants before they would consider accepting a job. The July 2019 CRRC and NDI survey suggests a gendered gap in the reserve price of labor as well: women want significantly less than men to start working on average. However, further analysis suggests that the gap only exists among the relatively well-off and not among poorer households.

On the survey, respondents that did not consider themselves employed were asked, “Considering your education and skills, what is the minimum salary you would agree to work for?” Eight percent of respondents asked the question refused to answer and 16% reported they did not know. Among those that did know how much they would want to start a job, the average was GEL 719. For men, the average was GEL 823 while for women, it was GEL 643 – GEL 180 less. Women’s lower reserve prices appear to stem from the larger share of women who report they would be willing to start working for GEL 500 a month (33%) compared with men (22%).

Further analysis of this question suggests that sex remains a significant predictor of the minimum salary someone would be willing to start working for, controlling for education level, settlement type, household wealth (proxied through the number of assets they own), age, and the presence of children in the household. Aside from sex, household wealth has a statistically significant association with the salary people want to start working. In Tbilisi and other urban areas, salary expectations are also higher than in rural settlements. Among the oldest age cohort in the survey (56+), expectations were lower.

However, after controlling for the interaction between sex and other variables rather than sex in and of itself, the data suggests that the interaction between a household’s wealth and sex is the key gender related factor when it comes to the reserve price of labor. There is no significant difference between the sexes in the reserve price of labor in poorer households. However, as wealth increases, men’s reserve price of labor increases at nearly twice the rate as it does for women: for every additional asset that a household owns, men want GEL 80 more to start working on average, compared to GEL 44 for women.

Rather than wanting more money to start working than men, women have lower reserve prices overall. While women want less to start working, this is only the case when women are in relatively better off households. In poorer households men and women that are not working are willing to start work at statistically indistinguishable wages.

Note: This blog post is based on two ordinary least squares regression analysis. The first controls for sex, age group, education level, household wealth (number of assets owned, from 11 asked about), settlement type (Tbilisi, Urban, Rural), and whether or not there is children in the household as independent variables. The dependent variable is the salary someone would want in order to start working. The second regression analysis looks at the interaction between all of the previously noted variables with sex. The data used in the above analysis is available here. The replication code can be found here.

This piece was written by Dustin Gilbreath, the Deputy Research Director of CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in this article do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in this article do not represent the views of the National Democratic Institute or any related entity.

Posted by

CRRC

at

2:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economic Situation, Employment, Gender, Monetary income, Sex

Monday, May 20, 2019

Grit among young people in Georgia

Angela Duckworth’s concept grit has gained a great deal of attention in recent years. Grit, described as some combination of perseverance and passion, has gained this attention, because the data suggest it is associated with a number of positive outcomes like employment and completion of education. In 2018, CRRC-Georgia measured the grit of over 2500 young people (15-35) within a baseline evaluation for World Vision’s SAY YES Skills for Jobs project (funded by the European Union within EU4YOUTH program) which is taking place in Mtskheta, Akhaltsikhe, Adigeni, Kutaisi, Zestaponi, Bagdati, Senaki, and Zugdidi. The data suggest that grit is good predictor of positive outcomes in Georgia as is it is in other contexts.

The grit scale is made up of 12 questions, measured on a five point scale, which were asked to a representative sample of young people in World Vision’s project area. The chart below shows the average score for each of the 12 statements.

The grit scale (average score on the above statements) is quite a good predictor of labor force participation. A person is considered outside the labor force if they do not have a job and are not interested in one, looking for one, or able to start one. A person is considered in the labor force if they are employed or are looking for a job, can start one, and are interested in one. The chances of whether someone will be in the labor force increase significantly as an individual’s grit increases. This pattern holds when adjusting for other factors including age, sex, parental education level, whether the person was displaced by a conflict, family size, and municipality. The chart below shows the probability of participation in the labor force adjusted for each these factors. It suggests that all else equal, if a person moved from the lowest score observed (1.4) to the highest (5), their chances of participating in the labor force would increase from 47% to 82%, a 35 percentage point increase in the probability of labor force participation.

The pattern is also quite consistent when looking across different demographic groups, with the pattern holding for women and men, people of different ages, from different socio-economic backgrounds, affected and not by the conflicts in the country, from large and small families and in the different municipalities the survey was carried out in.

The above data may suggest that grit may help in getting a job in Georgia, a positive story given that people often think connections are more important than hard work for finding a job. Given this, it also suggests that the grit scale works in Georgia as in other contexts, giving some amount of validity to it outside the United States where it has been used extensively.

The views presented in the above blog post are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of World Vision or the European Union.

Posted by

CRRC

at

10:51 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Employment, Georgia, Unemployment, Youth

Monday, February 12, 2018

What factors help to land a good job? Views in Armenia and Georgia

What are the factors that help one get a good job? The question is important around the world, and arguably even more important in countries with high reported unemployment, like Georgia and Armenia. While it would require an in-depth study of the labor market of a given country to find out what actually helps a person get a good job, what people think about this issue is also interesting. CRRC’s 2017 Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey asked the population of Armenia and Georgia which factors where important for getting a good job in their country.

In both Armenia and Georgia, connections was the most frequent answer, and was picked by almost a third of the populations. For this blog post, answer options are grouped into two categories: meritocratic and non-meritocratic factors. While the former includes education, professional abilities, work experience, and talent, the latter combines connections, luck, age, appearance and doing favors for the “right” people. In Georgia, approximately half of the population named meritocratic factors, while just above a third named these in Armenia.

Note: A show card was used during the interviews. Answer options “Other” and “Don’t know” (less than 5% if combined) are not shown on the charts in this blog post.

Although there are differences between Armenia and Georgia at the national level, a similar pattern is found when settlement types are compared within each country. The population of rural settlements in both countries tended to name meritocratic factors as important for getting a good job more often than the population of urban settlements.

In both countries, differences in the frequency of mentioning meritocratic vs. non-meritocratic factors were rather small among people with different levels of education. The only notable difference was that in Armenia, 39% of people with higher than secondary education named connections as the most important factor for getting a good job, while only 27% of those with secondary or lower education reported the same.

Note: Answer options to the question “What is the highest level of education you have achieved to date?” were recorded in the following way: “No primary education”, “Primary education”, “Incomplete secondary education”, and “Completed secondary education” were combined into the category “Secondary education or lower”. “Incomplete higher education”, “Completed higher education (BA, MA, or Specialist degree)”, and “Post-graduate degree” were combined into the category “Higher than secondary education”.

Overall, in both countries, connections were named most frequently as the most important single factor to get a good job. People in Georgia report the importance of meritocratic factors more often than in Armenia. In both countries, the rural populations name meritocratic factors more often than the urban populations, a fact which deserves further research to understand its underlying causes.

To have a closer look at CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer data, visit our Online Data Analysis portal.

Posted by

CRRC

at

11:47 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Caucasus Barometer, Economy, Employment, Georgia

Monday, September 19, 2016

Employment and income in Georgia: Differences by educational attainment

- What is the highest level of education you have achieved to date?

- A show card listing levels of education was used.

- Which of the following best describes your situation?

- A show card with the following answer options was used:

- Retired and not working;

- Student and not working;

- Housewife and not working;

- Unemployed;

- Working either part-time or full time (even if the respondent is retired / is a student), including seasonal work;

- Self-employed (even if the respondent is retired / is a student), including seasonal work;

- Self-employed (even if the respondent is retired / is a student), including seasonal work;

- Other.

- Which of the following best describes the job you do?

- A show card listing a hierarchy of job types was used.

- Speaking about your personal monetary income last month, after all taxes are paid, to which of the following groups do you belong?

- A show card with income groups was used.

Posted by

CRRC

at

5:35 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Education, Employment, Georgia, Monetary income

Monday, November 30, 2015

Parenting, gender attitudes and women’s employment in Georgia

Women’s employment can be beneficial for families and societies in many ways. The potential benefits for children when they have working mothers were recently described in an article published by the Harvard Business School. The findings of a cross-national survey covering 24 countries suggest that it is good for children under the age of 14 if their mothers work, instead of staying at home full time. The study showed that the sons of working mothers are more caring for family members compared with the sons of stay-at-home mothers. Probably more importantly, daughters raised by working mothers had greater career success and more stable relationships than the daughters of stay-at-home mothers. Other studies indicate that the relationship between women’s attitudes early in life towards gender roles and their later employment is recursive: “women’s early gender role attitudes predict their [adult life] work hours and earnings, and women’s work hours predict their later gender egalitarianism” (Corrigall and Konrad, 2007).

In October 2014, CRRC-Georgia conducted a nationwide public opinion poll for the National Democratic Institute (NDI) on attitudes towards gender issues in Georgia. A representative sample of 3885 respondents was interviewed in order to explore their attitudes towards women’s participation in society and politics as well as ideas about how to improve women’s position in society.

The survey’s results indicate that female unemployment may not be considered a serious problem by Georgians, because women are believed to be capable of self-realization even if they do not have a job. Moreover, unemployed mother’s children are believed to be better off compared to the children of employed mothers. The chart below shows that 65% of Georgians believe “It is better for a preschool aged child if the mother does not work” and a smaller but still considerable share (37%) is more radical, disagreeing with the opinion that “Employed mothers can be as good caregivers to their children as mothers who do not work”. Over half (55%) of Georgians think that because of household responsibilities, women cannot be as successful in their career as men, and just below half of the population (44%) think that “Taking care of the home and family satisfies women as much as a paid job”.

To take a deeper look into the data, explore it on our Online Data Analysis tool.

Posted by

CRRC

at

7:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Attitudes, Employment, Gender, Georgia, Women

Monday, June 22, 2015

Connections or education? On the most important factors for getting a good job in Georgia

By Nino Zubashvili

[Note: Over the next two weeks, Social Science in the Caucasus will publish the work of six young researchers who entered CRRC-Georgia’s Junior Fellowship Program (JFP) in February 2015. This is the first blog post in the series.]

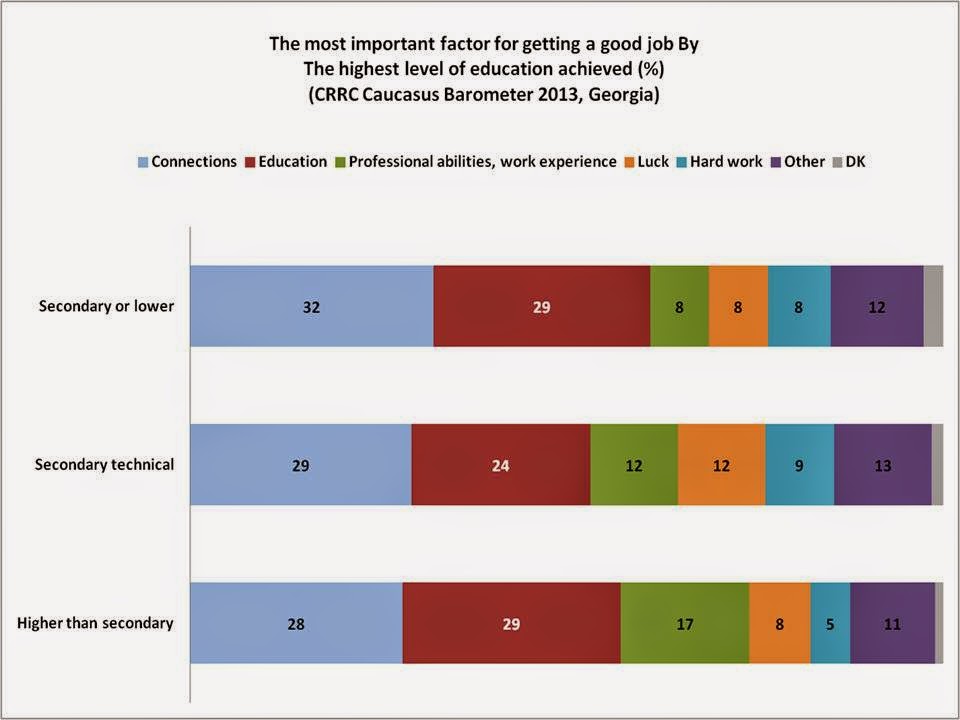

What is believed to be the most important factor for getting a good job in a country where unemployment is widely considered to be one of the biggest issues? CRRC’s 2013 Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey results show that connections (30%) and education (28%) are the most frequent answers to this question in Georgia. This finding is in line with studies on social capital in various countries, arguing that social ties provide people with better labor market opportunities (Lin, 1999; Mouw, 2003; McDonald and Elder, 2006), as well as with studies on the role of education in the job market, finding that education is an important resource worth investing in as it provides individuals with access to employment and better chances at obtaining well-paid jobs (Kilcullen, 1972;Smith and McCoy, 2009). Analyzing both the social ties and perceptions about what is reported as the most important factor for getting a good job, an earlier CRRC blog post, Finding a good job in Georgia, argued that Georgians without connections might be more likely to think that connections are the most important factor for getting a good job. This blog post, on the other hand, looks at how the answers about the most important factors for getting a good job differ by level of education and by employment status, with the aim of finding out who is more likely to think that education matters the most for getting a good job in Georgia.

CB 2013 data shows there is almost no difference in answers to this question between people having different levels of education. The only notable difference can be observed in relation to the perceived importance of professional abilities/work experience. While 17% of those with post-secondary education think this is the most important factor for getting a good job, 8% of those with secondary or lower education report the same.

Note: The answer options for the question, “What is the highest level of education you have achieved to date?” were grouped as follows: options “No primary education”, “Primary education (either complete or incomplete)”, “Incomplete secondary education”, and “Completed secondary education” were grouped into “Secondary or lower”. Options “Incomplete higher education”, “Completed higher education (BA, MA, or specialist degree)”, and “Post-graduate degree” were grouped into “Higher than Secondary”. For the question, “What is the most important factor for getting a good job in Georgia?” infrequently named answer options – “Age”, “Appearance”, “Talent”, “Doing favors for the ‘right’ people”, and “Other” – were grouped into “Other”.

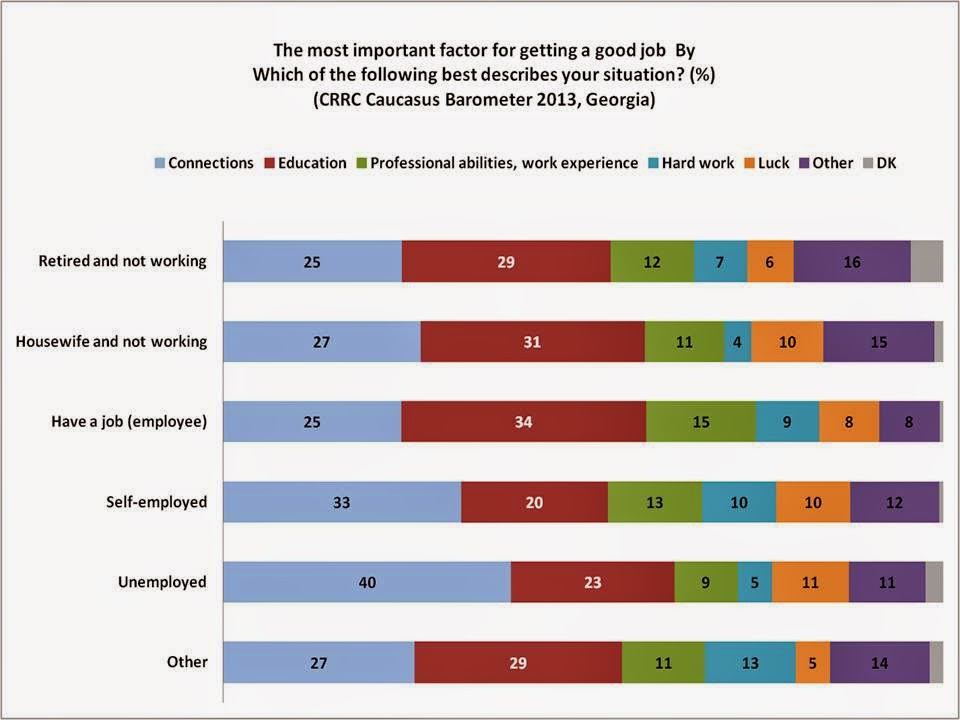

While there are few differences in perceptions about important factor(s) for getting a good job by education, such differences can be seen by employment status, and specifically between those who describe themselves as self-employed, employed and unemployed. Namely, 34% of the employed think education is the most important factor for getting a good job compared to 25% of the group who report connections. In contrast, the self-employed report that education (20%) is the most important factor for getting a good job less frequently than they report connections (33%). Those who consider themselves to be unemployed also name connections (40%) most frequently.

Note: To the question, “Which of the following best describes your situation?”, the following answer options – “Student and not working”, “Disabled”, “Other”, “Refuse to answer”, and “Don’t know” – were combined into “Other”.

This blog post has shown that while opinions about the most important factors for getting a good job in Georgia do not differ by education level, opinions do vary by employment situation. Those who describe themselves as employed more commonly think that education is the most important factor for getting a good job, while the self-employed and the unemployed most often name connections.

To learn more about CRRC surveys, visit our Online Data Analysis tool.

Posted by

CRRC

at

11:07 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: CRRC Fellowship, Education, Employment, Georgia

Thursday, January 22, 2015

A taxi driver’s tale, Part 2: The poverty of social status in Georgia

Looking at the association between an individual’s social status and his/her standing in the labor market, the first part of this blog post concluded that higher labor market mobility is characteristic for people with high social status, and that those with high social status have better chances of finding an attractive job. Yet, the question remains whether people with higher social status actually live better lives i.e., enjoy economic well-being and have better perceptions about their and their children’s future. To answer this question, this blog post examines how social status is associated with individual and household well-being. Data again comes from CRRC’s 2013 Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey.

According to Geostat, the subsistence minimum in Georgia was GEL 137 in 2013 (approximately USD 80). CB 2013 asks a question about personal income last month, but the answer options are given in categories (income ranges). The subsistence minimum of $80 falls into the category between $51 and $100. It is used in the blog post as a reference category to compare, on the one hand, individuals with higher incomes and, on the other hand, individuals with lower incomes. The group of respondents reporting not having personal income are considered a separate group.

As expected, social status is positively associated with personal income. Almost half of the representatives of the high social status group made more than $100 last month, whereas only 30% of the low status group and 36% of the middle status group managed to exceed the same threshold. Interestingly, the no income category prevails in the high and middle social status groups. One in every three people in these groups reports having no personal income compared to one in every four in the low status group.

Unsurprisingly, the higher its social status, the more money a household spends. Geostat reported GEL 900 (approximately USD 500) as average monthly household expenditures in 2013. In CB’s corresponding question, this falls into the category between $401 and $800. Again, this is used as a reference category to differentiate households spending more than the average from households spending less than the average. A higher social status is still positively associated with higher spending. However, the overall economic condition of Georgian households looks quite poor. As the chart below shows, even in the high social status group, the majority of households spent under $401 last month, and only 19% spent more than the reference category. In the low social status group, almost everyone (91%) spent less than the reference category, meaning that the low status group households spend significantly less than Georgian households on average.

The poor economic condition of the majority of the Georgian population is confirmed by CB questions about personal savings and debt. The vast majority of Georgians do not have savings, regardless of their social status. However, the high social status group (17%) is almost twice as likely to have some savings compared with members of the low (8%) and middle (9%) status groups. Likewise, money is more often owed to the representatives of the high status group (25%) compared to the middle and low status group members (18% and 12% respectively). The data does not show significant differences in terms of personal debts. Approximately 40% of each group reports owing money.

So far, it has been demonstrated that high social status is helpful to overcome economic hardship, but does not guarantee it. The reported gap between a household’s income and the amount of money it needs to cover its basic needs reinforces this statement. Half of the high status group representatives affirm that during the past 12 months there were occasions when their household did not have enough money to buy food. In the middle and low status groups, more than 70% reported the same. Moreover, the majority of the middle and low status groups and 40% of the high status group had to borrow money to cover utilities in the past six months.

The chart below shows that even representatives of the high social status group can largely satisfy only basic needs. Half reported that money is enough for food and clothes, but not for expensive durable goods (a new refrigerator or washing machine, for example). In the low status group, 35% stated that money is not enough even for food. Interestingly, a quarter of the middle and one in every ten of the high status group report facing the same problem.

It is not surprising that the poor economic realities of households are reflected in perceived place on an imaginary economic “ladder”. The chart below shows that only 19% in the high social status group perceive their household’s economic rung as high (45% place their households on the middle rungs and about one third towards the lower end). In the middle and low social status groups, the majority believes their households stand on the low rungs (46% and 54% respectively).

Note: Original answers were on a 10-point scale. For this graph, answers were re-coded as follows: rungs 1 through 4 – Low, rungs 5-6 – Middle, rungs 7 through 10 – High.

At the same time, belonging to a higher social status group helps people to be more optimistic – 71% of the high status group believes that they will be better off in five years. Despite pressing current economic conditions, the other two groups are also quite optimistic – 57% of the middle and 43% of the low status group believe in a better future. Optimism absolutely flourishes, and the relevance of current social status fades when individuals contemplate their children’s future. Over 90% of all social status groups believe in a brighter financial situation for their descendants. Notably, all three status groups agree that the most important factor that will contribute to the well-being of the next generation is education.

This blog post described how social status is associated with economic well-being and perceptions about the future. The most important message to the taxi driver is that a higher social status in contemporary Georgia leads to more mobility on the labor market, as well as relatively higher income and spending. However, social status alone is hardly enough to overcome poverty and substantially improve well-being. Perhaps this explains why a man with more than one university diploma chooses to continue driving a taxi.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:26 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economic Situation, Employment, Georgia, Index, Social Capital

Monday, January 19, 2015

A taxi driver’s tale, Part 1: Social status in the Georgian labor market

Taxi drivers tell perhaps the most telling story of Georgia’s economic transition. They often complain that the transition made their high social status useless, thus pushing them into taxi driving. This often heard and mocked complaint highlights the contrast between what is expected from and what is delivered by the labor market. Taxi drivers expect their social status to remain at work in economic life, while the mockers believe that social status has no relevance for Georgia’s current labor market. Based on CRRC’s Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey data, this blog post shows that the taxi drivers are not entirely wrong. According to 2013 Caucasus Barometer survey, higher social status is associated with a higher likelihood of employment, a better job, and greater mobility on the labor market.

The taxi drivers often “operationalize” their social status as having a diploma or two from one or more higher educational institutions. In Georgia, another common cue to signal high social status is family background, normally operationalized in the same way. Not only are these two cues at the core of the taxi driver’s tale, but notably, the same characteristics often prevail when traditionally selecting a favorable bride or groom. Hence, the two cues fit the Weberian understanding of social status as perceived prestige and esteem that is related to economic relations, but cannot be reduced to it.

Following the taxi drivers’ perspective, this post proposes a simple index of social status, which includes two components: (1) respondent’s level of education, and (2) level of education of the respondent’s parents. In both cases, education variables are recoded so as to have three categories: (1) secondary or lower education, (2) secondary technical education, and (3) incomplete or complete tertiary education.

The index is a simple sum of these indicators and hence, it ranges from 0 to 4. At the highest extreme of the index stands a person with tertiary education having at least one parent with tertiary education (score 4). A person without any of these characteristics stands at the lower extreme of the continuum (score 0). Individuals with scores between the extremes are counted as having middle social status. As shown below, more than half the population belongs to the middle status group, whereas 28% and 19% fall into the low and the high social status groups respectively.

Looking at the distribution of social status groups across settlement type, age and gender, it is notable that 39% of Tbilisi residents are in the high status group compared to only 7% of residents of rural areas. Low (42%) and middle (51%) status groups are predominant in rural areas. Urban settlements outside the capital have the highest percentage of the middle status group (62%). Interestingly, no important differences can be observed by gender. Younger cohorts tend to have higher education as well as more educated parents compared to older cohorts, and are thus more likely to belong to a higher status group.

But, does social status have implications for an individual’s standing on the labor market? The Caucasus Barometer uses several questions to measure respondents’ employment status. While those who are employed or self-employed are identified using one survey question (“Which of the following best describes your situation?” with answer options including “Working either part-time or full-time” and “Self-employed”), identifying the unemployed is a trickier affair. To do so, it is necessary to separate those who do not work by choice and those with physical constraints to labor force participation from those who do not work resulting from a failure to find a job, i.e. the unemployed. To identify the latter group, a combination of two questions has been used - is the respondent interested in a job and if so, is he or she ready to start working within two weeks if a suitable job were available. Respondents who do not meet these two conditions are not formally unemployed and are not counted as part of the active labor force.

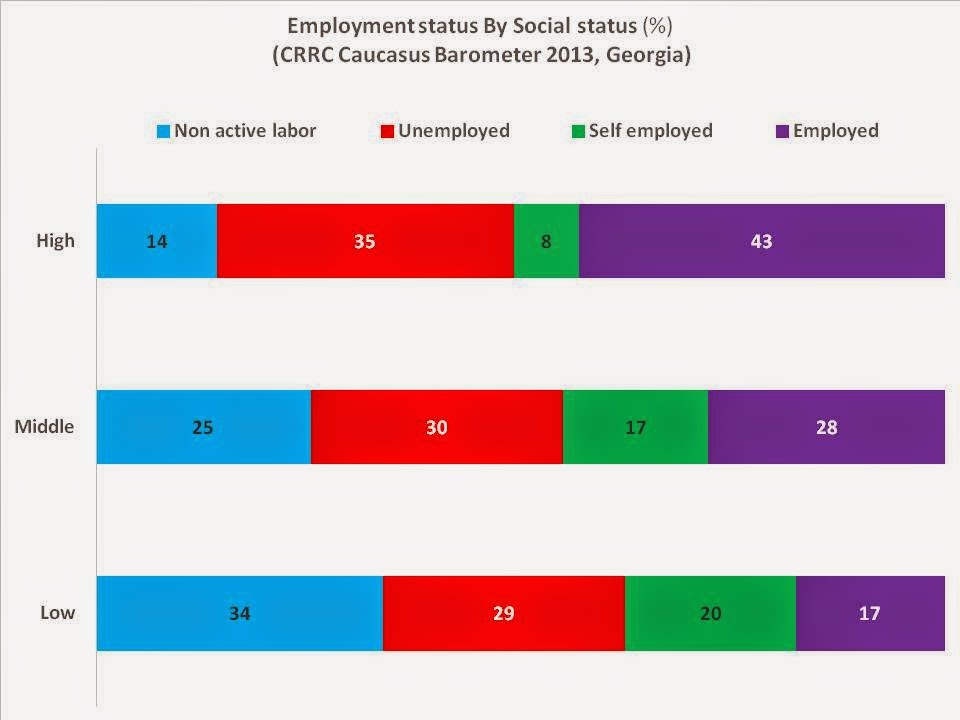

From cross-tabulating an individual’s social status and his/her employment status, it is evident that the plurality of the low status group is out of the labor force (34%) or unemployed (29%). In contrast, the plurality of the high status group is employed (43%). However, it is noteworthy that one in three of the high social status group is unemployed (35%), while almost half of the individuals with low social status, on the other hand, were never employed.

Thus, the higher the individual’s social status, the higher his/her employment chances. Moreover, the status group a person belongs to indicates his/her occupational status. More than half of the high social status group works in high status positions, i.e. managers and professionals. A plurality of the low social status group (41%) works as unskilled laborers (elementary occupations, sales people, and baby sitters). Nonetheless, the majority of the low and middle status group enjoy mid-level occupations, such as technician, clerk, or skilled agriculture worker.

Note: The variable used to measure occupational status is JOBDESC. Respondents were asked, “Which of the following best describes the job you do?” Suggested answer options included: Manager; Professional; Technician / Associate professional; Clerical support worker; Service / Sales worker; Skilled agricultural / Forestry / Fishery worker; Craft and related trades worker; Plant and machine operator / Assembler; Elementary occupation; and Armed forces occupation. For this blog post, the options “Manager” and “Professional” were combined into the category ‘high’. “Armed forces occupations”, “Plant and machine operators”, “Craft and related trade workers”, “Skilled agricultural workers”, “Clerical support workers”, and “Technicians” were combined into the category ‘middle’, and “Elementary occupations” and “Service/sales workers” were grouped into the category ‘low’.

Social status is also associated with employment sector and type of work for those who work. People who belong to the high status group rarely own businesses (18%) and are generally either state employees (41%) or employees of private companies (40%). At first glance it may seem paradoxical that those in the lower status group are more likely to own a business (55%), however, taking a closer look at Georgian reality makes it clear that these business owners are mostly self-employed agricultural workers or petty traders. Those in the middle status group are more or less equally distributed between the public, private and self-owned business sectors. As noted, people belonging to the low and middle status groups are more likely to work in agriculture (40% and 19% respectively). Individuals in the high status group are employed by educational institutions (24%) more often than in any other sector.

Importantly, the data shows that the Rose Revolution marked an important threshold for the Georgian labor market. The majority of employed individuals of all status groups started working at their primary workplace after 2004. This year perhaps also marked an important shift in the structure of the economy as 46% of the high and 33% of the middle status groups lost their job after 2004.

Not only are high status individuals more mobile, but so too are their household members who were more than twice as likely to find a new job in the last 12 months compared to the household members of individuals belonging to the low status group (16% vs. 7%). However, exactly the same was true about losing a job in the last 12 months – household members of those in the high status group lost jobs twice as often as those in the low status group.

This blog post has shown that the taxi driver’s tale of frustration has an observable underpinning – social status, operationalized as an individual’s and his/her parents’ education, is associated with an individual’s standing on the labor market. People belonging to the high status group are more likely to be employed, generally have better jobs, and exhibit greater mobility on the labor market. Hence, the preliminary conclusion drawn from this blog post is optimistic for the taxi driver, who perceives his current job as inferior to his status. If he belongs to a high social status group, he is more likely to find a better job. The second blog post in this series will describe how social status is related to household income and spending, as well as an individual’s perceived economic rung.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economic Situation, Employment, Georgia, Index, Social Capital

Monday, December 15, 2014

How does job satisfaction vary by job profile?

A number of fields, including economics, sociology and psychology, study issues related to job satisfaction. Using CRRC Caucasus Barometer (CB) 2013 data, this blog post looks at how job satisfaction differs by job profile.

For the first time in 2013, CB used the International Labour Organization’s International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) to measure the status of respondents’ jobs (referred to as “job profile” for the rest of this blog post). The level of job satisfaction was measured using the following questions:

- “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the statement: ‘I am doing something that many people need?”

- “Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your job?”

- “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the statement: ‘I feel valued at work?”

According to CB 2013 data, Georgians with different job profiles report different levels of perceived importance for their job. Georgians holding a high profile job are nearly twice as likely (75%) as Georgians holding low profile jobs (40%) to think that they are doing something that many people need.

Note: Suggested answer options for the job profile question included Manager; Professional; Technician / Associate professional; Clerical support worker; Service / Sales worker; Skilled agricultural / Forestry / Fishery worker; Craft and related trades worker; Plant and machine operator / Assembler; Elementary occupation; and Armed forces occupation. Each of these categories suggests a different level of qualification, payment and prestige. For this blog post, the options “Manager” and “Professional” were combined into the category ”high profile occupations,” while the other categories were grouped into the category “low profile occupations.” Options “Don’t know” and “Refuse to answer,” relevant for less than 3% of the employed, were excluded from the analysis. It should be mentioned that the findings presented in this blog post only apply to Georgians who reported having a job at the time of the interview (39% of the sample), and that the ratio between high and low profile occupations is not equal (23% and 77%, respectively).

Similarly, the assessments of job satisfaction also differ by job profile. The share of employed Georgians who report being satisfied with their job is greater among high profile job holders.

Following the same logic, the number of respondents who completely agree with the statement “I feel valued at work” is nearly twice as high among high profile job holders (47%) than among low profile job holders (25%).

Job satisfaction varies by job profile among employed Georgians. The charts above indicate these differences: the employed who believe they do an important thing for others and feel valued at work tend to have high profile jobs (managers, professionals). For more data on job profiles in Georgia and the South Caucasus check out the CRRC’s Online Data Analysis tool, here.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:22 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Employment, Georgia, Job satisfaction, Valued at work

Monday, October 13, 2014

Active and Employed

According to data from CB 2013, 40% of Georgians are either employees (25%) or self-employed (14%). In this survey, those who do not have a job are grouped into the following categories: unemployed (25%), retired (17%), housewives (12%), students (4%) or disabled (2%). One can reasonably expect that people who work are more likely to have less time to participate in different kinds of activities compared to the unemployed. However, CRRC Caucasus Barometer data demonstrates that people who work tend to get involved in different kinds of activities more frequently than those who do not work.

Working people are more likely than the unemployed to participate in activities which involve socializing, meeting new people and helping others. Twenty five percent of those who have a job said that they have volunteered without compensation and 23% have attended a public meeting during the last six months, while only 17% and 13%, respectively, of the unemployed did the same. Also, when asked whether they have done any unpaid or paid work for their family’s business for at least one hour within the past week, more of those who work answered positively compared to the unemployed.

Those with jobs and without are similar in their frequency of using the internet but differ from each other in respect to their behavior while browsing the internet. As CB 2013 shows, 36% of those who work and 31% of the unemployed say they use the internet every day. The most frequent activities when browsing the internet are similar in both groups, but the frequencies are different between groups. Most of the time, people use the internet to visit social networking sites or to search for information, though those who have a job are less likely to use the internet for social networking sites and are more likely to search for information. They are also more likely to send and receive email, which may be related to their work.

Thus, people who work are more involved in other social activities than those who do not work. In addition to financial factors, social factors may also be behind these differences. Maybe those who have a job have more opportunities to engage in activities, because they have more connections as they are part of a specific social network due to their work. On the contrary, maybe they have a job, because they already had more social ties before they got a job, and thus are and were actively involved in many different activities. We cannot say for sure, but finding out the answer might be very important as, according to Caucasus Barometer 2013, there are a fair number of unemployed people (25%) in Georgia who may have free time that can be used to serve some good.

In your opinion, why are the unemployed less involved in the social activities discussed in this blog? What is the reason for unemployed people not participating in many social activities? Is it only related to economic factors or are there other factors that could explain these findings?

Posted by

Anonymous

at

10:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Employment, Georgia, Social Capital, Unemployment

Monday, September 29, 2014

Georgians Have High Hopes but Little Information about the Association Agreement with the EU

Optimism abounds with regards to the recently signed Georgia-European Union Association Agreement (AA). Most Georgians, however, lack information about the EU and its relation to the country, including the details of the agreement which directly concern the future of Georgia’s economy. The AA covers many areas including national security, migration, human rights and the rule of law but is primarily a free trade agreement with potentially major implications for employment.

Surveys have consistently shown that Georgian citizens are primarily concerned with unemployment and other economic problems, but academic opinions are divided on whether the AA’s impact on unemployment will be positive or negative; Messerlin, Emerson, Jandieri and Le Vernoy (2011) emphasize the “extremely onerous” costs of complying with EU regulatory standards while Kakulia (2014) argues that short-term costs will be more than offset by augmented inward foreign direct investment and expanded export volumes. This blog post analyzes public opinion surveys as well as academic research on the Association Agreement and finds discordance within the attitudes of the public. While much of the public have high hopes about the country’s integration with the EU, close ties may not improve the employment situation, which the majority of citizens see as Georgia’s most pressing problem.

Georgians tend to view potential EU membership positively, with the CRRC 2013 Caucasus Barometer survey finding that when asked “To what extent would you support Georgia’s membership in the EU?” 34% of adults responded “fully support” and 31% “rather support.” While demonstrating optimism most citizens are ill-informed about the EU and what closer ties mean for the country’s future. For example, in the Eurasia Partnership Foundation’s Knowledge and attitudes toward the EU survey in 2013 only 23% of the population reported familiarity with the Eastern Partnership, (a crucial forum for EU-Georgia dialogue) and only 19% responded “Yes” to the question “Have you heard or not about the Association Agreement with the European Union?”

While Georgians overwhelmingly see EU integration in a positive light, their focus rests primarily on the problem of stubbornly high unemployment, which could be profoundly impacted by the conditions of the AA. The 2013 Caucasus Barometer confirmed a series of studies emphasizing public awareness of the unemployment problem, finding that 54% of adults in Georgia view it as the “most important issue facing Georgia,” dwarfing such options as “unsolved regional conflicts” and “problematic relations with Russia.” That should not come as a surprise, as recent numbers from the National Statistics Office of Georgia give the unemployment rate at 14.6%, high by almost any standard, while some studies have found that the actual figure is upwards of 30%.

EU-Georgia relations and unemployment are closely intertwined because the AA includes a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), meaning that in addition to dissolving tariffs on all imports from EU member states the country will have to adopt EU regulatory standards on products. Academic opinions are split as to whether this will be helpful or harmful to the employment situation. In the words of Vato Levaja of the Free University of Tbilisi, “we need to adjust to the EU regulations, which are, to put it in a nutshell, the luxury of a richer community…you have to pay for it.” This adjustment could be especially difficult for agriculture producers who must bear the financial burden of meeting stricter food safety standards. Some manufacturers will also need to make costly investments in order to improve the quality of their products. Higher operating costs combined with increased foreign competition (due to the removal of tariffs) could hurt the profitability of some firms, putting downward pressure on employment, at least in the short term.

Proponents of the agreement argue that by improving its regulatory standards Georgia will attract more foreign investment and be able to export products to a wider range of foreign markets. More stringent regulation means better products and more productive industries, thereby increasing national wealth and employment opportunities. That may well happen, but the process will be difficult and likely only bear fruit in the long-term. However, as Georgians see unemployment as the biggest issue facing the country it is important that citizens become better informed about the Association Agreement’s economic implications. While Georgians tend to expect positive outcomes from integration the jury is out on whether deeper ties with the EU will help expand employment opportunities.

For additional insights relating to Georgian attitudes toward EU integration refer to this July post concerning expectations for the Association Agreement or take a look at our data using the CRRC’s Online Data Analysis tool. The website of the EU Delegation to Georgia offers a wealth of information on the Association Agreement.

Posted by

Anonymous

at

10:41 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economy, Employment, European Union, Public Opinion, Unemployment

Monday, August 12, 2013

Gender inequality in the South Caucasus

Posted by

Anonymous

at

11:36 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Employment, Gender, Labor, South Caucasus, Women