CRRC-Georgia’s survey conducted in August 2017 for the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) asked about livestock owned by rural households in Georgia, including cows, bulls, buffalo, pigs, sheep, and goats. Cows and bulls were reported to be owned most commonly. Some of the questions the project addressed the division of tasks between men and women in taking care of livestock, while other questions tried to find out whether there were gender differences in making major decisions related to livestock and livestock products.

Men and women reported spending about the same amount of time on animal care during a regular day. However, men were reported more frequently to feed the animals and take them to pasture. In contrast, milking animals, whenever relevant, was most often reported to be done by women. The task of taking care of animals when they get sick was most often reported to be shared equally by male and female members of a household.

Note: Households consisting of only male or only female members were excluded from the analysis in this blog post. Original answer options “Mostly hired men”, “Mostly hired women” and “Hired men and women equally” were combined into the category “Hired workers”.

If livestock or any livestock products were sold, decisions were reported to be taken most often jointly by male and female members of the household. When it comes to selling, vaccinating or registering livestock, however, the next most common response was “mostly male members of the household.”

While there are gender differences in taking care of livestock in rural Georgia, when it comes to decision making, people report most often that men and women make decisions together.

To explore the issue in greater depth, see CRRC-Georgia’s report for FAO. To explore the data, visit our online data analysis portal.

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Livestock care and livestock-related decision making in rural Georgia: Are there any gender differences?

Posted by

CRRC

at

11:37 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Gender, Georgia, Rural

Monday, December 11, 2017

Evaluation of the Impact of the Agricultural Support Program

In line with the Internal Office of Evaluation of IFAD’s methodology, impact was assessed across five specific domains. These include: (i) household income and assets; (ii) human and social capital and empowerment; (iii) food security and agricultural productivity; (iv) natural resources, the environment and climate change; and (v) institutions and policies. While the focus of the evaluation is on the rural poverty impact criterion, the performance of the programme has also been evaluated for impact on gender equality and women’s empowerment.

The evaluation assessed not only “if”, but also “how” and “why” the programme has or has not had an impact on selected households and communities in the programme area. To this end, the evaluation team adopted a mixed methods approach including a household survey, focus group discussions, in depth interviews, and key informant interviews. The survey consisted of 3190 interviews, with 1778 interviews in control households and 1412 in treatment households.

In order to test for impact, the team used a quasi-experimental survey design. The driving idea behind quasi-experimental analysis is to use counterfactuals to understand what would have happened in the communities which received interventions had the intervention not taken place. Given that ASP did not make use of randomization, a two staged matching procedure was used to achieve balance on observable variables. First, treated communities were matched with non-treated communities on a number of variables. Second, after data collection households were matched using multivariate matching with genetic weights. Finally, when feasible, a differences in differences approach was used, with changes measured rather than only the 2016 outcome. Regression analyses were then used to estimate effects.

The key findings of the impact analysis include:

- Indirect beneficiaries of the leasing component – individuals who sold grapes to companies that received leases – had substantively large increases in agricultural incomes;

- Analyses often suggest little if any impact when it comes to rural poverty. However, context is important. During the project period, ASP was a small part of the very large aid inflows to Georgia, much of which was directed to the area where ASP activities took place. Hence, a lack of significant changes suggests that ASP performed on par with, but not better than other aid projects which took place in control communities;

- Project outreach in the small scale infrastructure communities was inadequate, resulting in less effective project design and missing an opportunity for the development of human and social capital;

- The project’s main success within the food security and agricultural productivity impact domain is the increase in amount of land irrigated; the project does not appear to have had any detectable impact on food security;

- ASP does not appear to have contributed to the sustainable development of the agricultural leasing sector in Georgia;

To read more about the impact evaluation, see the full report, which is available here.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Evaluation, Georgia, Methods

Monday, November 13, 2017

Who should own land in Georgia? How attitudes changed between 2015 and 2017

[Note: This article originally appeared on OC-Media. It was written by Kristina Vacharadze, Programmes Director at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia or the Europe Foundation.]

Georgian parliament recently adopted constitutional amendments. Among the many changes were those regulating the sale of agricultural land. According to the amendments, “Agricultural land, as a resource of special importance, can only be owned by the state, a self-governing entity, a citizen of Georgia, or a union of Georgian citizens.” While the constitution allows for exceptions, which should be regulated by a law yet to be written, it is expected that foreigners will not be allowed to buy agricultural land in Georgia as freely as Georgian citizens. This blog post looks at public opinion about foreigners owning land in Georgia.

A majority of the population (64%) think that land should only be owned by Georgian citizens no matter how they use it, according to the EF/CRRC survey on Knowledge of and Attitudes toward the EU in Georgia (EU survey) conducted in May 2017. This share increased by 21 percentage points since 2015.

Note: The original 11-point scale was recoded into a 5-point scale for the charts in this blog post. Codes 0 and 1 were combined into ‘Only citizens of Georgia should own land in Georgia, no matter how they use this land’; 2 and 3 into ‘2’; 4, 5 and 6 into ‘3’; 7 and 8 into ‘4’ and codes 9 and 10 - into ‘Land in Georgia should be owned by those who will use it in the most profitable way, no matter their citizenship’.

The rural population is least favourable to the idea of foreign ownership of Georgian land. A large majority (74%) strongly believe that only citizens of Georgia should own land.

The younger population (18-35 years old) is more open towards foreigners owing land in Georgia. Approximately one in five believes that land should be owned by those who will use it in the most profitable way, irrespective of their citizenship. Older people are less open to foreign ownership. Still, in 2017 the proportion of young people who are more open towards foreigners owning land in Georgia dropped by seven percentage points compared to 2015, while the proportion of young people who think that the land should be owned only by Georgian citizens increased by 22 percentage points.

The majority of the population of Georgia do not favour foreigners buying land in the country. Younger people and those living in urban settlements appear more open to the idea of foreign ownership of Georgian land. But the number of those opposing foreign ownership of Georgian land is high and has increased in the past two years.

Explore the data used in this blog post further using our Online Data Analysis tool.

Posted by

CRRC

at

3:55 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, European Union, Georgia, Nationality, Survey

Monday, July 18, 2016

Environmental issues in Georgia: a concern for all?

[Note: This post was first published on Friday, July 15th at the Clarion.]

By Sacha Bepoldin

The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) has highlighted that “Environmental decline adversely affects the health, well-being and livelihood opportunities of the individuals affected by pollution or natural resource depletion. Soil erosion, deforestation, the loss or depletion of animal and plant species limit the productive opportunities of vast numbers of people.” In Georgia, according to the 2009 National Report on the State of the Environment of Georgia and the 2012-2016 National Environmental Action Programme, the increasing number of natural disasters, chemical pollution of soils and progressing desertification, mainly in Shida Kartli, Kvemo Kartli and parts of Kakheti, are clear signs of man-made pollution. Both rural and urban inhabitants of Georgia are affected by environmental problems, albeit of a different nature. As public opinion data shows, people assess the importance of environmental problems differently. This blog post examines the salience of pollution as an issue for the settlement where people live and the relative importance of this problem compared to other issues, using the CRRC/NDI August 2015 survey.

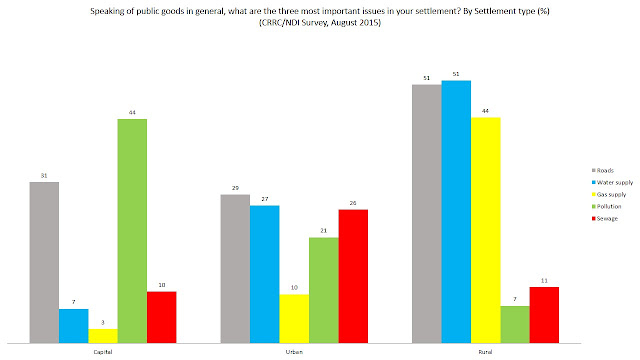

One of the questions asked during the survey was, “Speaking of public goods in general, what are the three most important issues in your settlement?” Pollution was the fourth most frequently mentioned issue countrywide, after roads, water supply and gas supply. There are, however, differences in the frequency of naming these issues by settlement type. While pollution was the main issue in the capital, named by 44% of Tbilisi residents, it was named by only 7% of the rural population.

Note: The sum of answers does not add up to 100%, since respondents could name up to three issues. The charts in this blog post display only the five most frequently named issues at the national level.

At the national level, improvement of the water supply and roads are the public’s highest priorities in terms of budget spending, while pollution again ranks fourth. Pollution represents the highest priority for the population of Tbilisi, but only 1% of the rural population thinks spending on pollution should be a budgetary priority.

The rural population likely underestimates the importance of pollution and environmental issues in general. At the same time, a study conducted by the University of Gothenburg highlighted that degrading agricultural practices affect 35% of farmland in Georgia, which is already scarce due to the mountainous landscape of the country. As agriculture, according to official sources, is the main employment sector in the country, such practices threaten the lifestyle and economic opportunities of a large share of the population. Given the disconnect between lack of concern over this issue in rural settlements, on the one hand, and the likelihood that it affects the rural population, on the other hand, a communication campaign focused on environmental protection, especially in rural settlements, could help prevent further environmental problems.

To look through the data in more depth, visit CRRC’s Online Data Analysis platform.

Posted by

CRRC

at

7:18 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Environment, Georgia, Rural

Thursday, December 04, 2014

SME Performance in Georgia and Armenia: Part 2

As discussed in the first blog post of this series, the results of the CRRC Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey show that Georgians demonstrate higher levels of interpersonal and institutional trust than Armenians. These types of trust are important indicators of social capital, which is often taken as a necessary condition for the presence of a robust, productive entrepreneurial class and small and medium enterprise (SME) sector. While Georgians express higher levels of trust in their fellow citizens as well as in formal institutions such as the judiciary and Parliament, economic data shows that the country’s SME sector suffers from a dearth of productivity. This blog post looks at survey data shedding light on economic conditions in Georgia and Armenia as well as policy research on the state of SMEs in each country, finding impediments to rural development and the high cost of financing to be potential causes for the relative lack of productivity by Georgian SMEs.

Productivity of the SME sector (defined as value added per employee) is significantly lower in Georgia when compared to Armenia. Emblematic of the lack of productivity in Georgian SMEs is the preponderance of small-scale agriculture. Many legally designated “small enterprises” are in fact subsistence agriculture proprietorships with little or zero cash turnover, a situation which Rudaz 2012 refers to as “entrepreneurship by default.” A report from the International Fund for Agricultural Development found that as late as 2005, 83% of rural households were dependent entirely on subsistence agriculture and that a “typical” rural household consumed 73% of what it produced. By 2013, however, the CB found that 59% of rural Georgians reported receiving household income from the sale of agricultural products, indicating an existence at least slightly above subsistence level agricultural production. On the other hand, 27% of Georgia’s rural inhabitants reported no household income from salaries or sales of agricultural products. Rural Armenians are somewhat less likely to sell agricultural products (50% reported household income from this source), but more likely to receive salaries. However, 25% percent of rural Armenians responded “no” to their households having received income from either source. Thus one cannot decisively discern from the data at hand whether rural Armenians are more likely to receive cash income than rural Georgians.

The first blog post of this series determined that available measures of social capital appear to be insufficient to explain differences in SME productivity between the two countries. So, what are possible causes for the lack of productivity gains in Georgia’s SME sector? With regards to agricultural SMEs, a potential culprit mentioned in the previous installment of this series is the fragmentation of agricultural land, with the average private holding in the country being only 1.25 hectares. The consolidation of small plots into larger and more efficient commercial farms has been impeded by an inefficient system of land registration and poorly defined property rights. Restrictions on the purchase of agricultural land by foreigners and foreign-owned businesses have also precluded potentially productive investment in the sector. While the Constitutional Court struck down a law banning land purchases by foreigners in June, 2014, a new draft of the law will allow private foreign persons and foreign companies established in Georgia to purchase plots of up to 100 hectares. Fragmentation is a problem in Georgia, but it also bears mentioning that the average private plot in Armenia consists of 1.3 hectares, scantly larger than in Georgia. Land fragmentation appears to be an obstacle to the growth of Georgia’s SME sector, but it doesn’t appear to be a decisive one.

As for palpable factors which may explain the lack of growth by both Georgia’s agricultural and non-agricultural SMEs, the difficulty of obtaining financing should not be overlooked. The average interest rate spread in Georgia (the difference between the interest paid on deposits and the interest charged on loans) is 11.3%, the highest spread of the former Soviet republics and significantly higher than the average spread of 7.3% in Armenia. This means that the cost of borrowing outstrips the incentive to save, with the result being that an entrepreneur in need of financing to buy land and equipment or hire employees is faced with very high borrowing costs. In Armenia, this problem occurs but on a smaller scale.

The high cost of financing stems in part from the lack of collateral held by SMEs, which discourages lending. Rudaz also reports the existence of a “law giving tax authorities the right to use the collateral of tax payers who owe money to fiscal authorities,” which allowed the tax authorities to seize the collateral of those owing back taxes. To be more specific, in cases in which a person has outstanding debts to both the tax authorities and a financial institution, the claims of the tax authorities take precedence. This interpretation was corroborated by Eka Gigauri of Transparency International Georgia. As a result, domestic financial institutions face higher financing costs when borrowing from abroad, and banks have become reluctant to accept collateral. There is also a general sentiment of political risk associated with Georgia; the country has a moderate-to-low credit rating of BB-, which hampers the ability of banks to procure external funding. These developments translate into higher borrowing costs for households and businesses.

To summarize, academic studies produced by Knack and Keefer (1997) and Bjornskov and Meon (2010) emphasize the importance of social capital on the success of entrepreneurship, and CB survey data show that Georgians exhibit significantly higher levels of social and institutional trust (which are among important indicators of social capital) than Armenians. Social trust is often taken as a necessary condition for economic growth. However, it is not a sufficient condition, as indicated by measurements of productivity (SME turnover per employee) being much higher in Armenia than in Georgia. This indicates that more palpable factors are inhibiting the growth of Georgia’s SMEs, with agricultural land fragmentation and the difficulty in obtaining financing being possible explanations. However, it must be conceded that none of the factors presented in this study, when viewed in a vacuum, appear sufficient for explaining the divergent performances of SME sectors in Georgia and Armenia. A more comprehensive study is necessary to reach solid conclusions.

For more information about public opinion in the South Caucasus, including data pertaining to social capital and the economic situation, refer to the CRRC online data analysis tool. If you have some criticisms, evidence or insights to add to the discussion, please feel free to contribute comments.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:34 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Armenia, Economic condition, Georgia, Social Capital

Monday, March 31, 2014

This land is my land and this land is your land

On June 28, 2013 the Georgian parliament passed a law placing a moratorium on agricultural land sales to foreigners until the end of December 2014. Agriculture has been called one of the pillars of the Georgian economy as 53% of Georgians were employed in agriculture in 2011 according to a European Union Neighborhood Programme report. Furthermore, agricultural investment has been the focus of both the current Georgian Dream coalition government, as well as the previously governing United National Movement. As a blog by the International School of Economics at Tbilisi State University highlights, the question then becomes, if Georgia wants to invest in agriculture, where will the money come from if not abroad? This blog looks at how Georgians feel about doing business with different ethnic groups as well as how Georgians feel about Georgian women marrying outside their ethnic group. The post also considers knowledge of foreign languages in rural areas in order to highlight that communication between Georgian and foreign farmers would be difficult without a common language.

Approximately 2,000 Indian farmers settled in Georgia according to a 2013 BBC report. This led to the incitement of protests particularly in the eastern Georgian province of Kakheti in 2013. The 2010 Caucasus Barometer asked Georgians how they felt about doing business with Indians. Results of the survey showed that 64% of rural Georgians approved of doing business with Indians compared to 71% of Georgians in Tbilisi. By looking at how Georgians living in rural areas feel about doing business with other ethnic groups, we can see how the Georgians most likely to be involved in agricultural activity might be inclined to working with foreign agricultural investors. The following graph shows that doing business with Iranians, a group that has also been reported to be investing in agricultural land in Georgia, is approved of by 59% in rural areas, compared to 86% in Tbilisi.

A further way of gauging how rural Georgians feel about foreigners is looking to whether they approve of Georgian women marrying other ethnic groups. Though Georgians generally are against marriage to foreigners, rural residents consistently disapprove of Georgians marrying other ethnic groups more often than Tbilisi based Georgians. The following graph shows this relationship for Russians, the ethnic group which Georgians are most likely to approve of Georgian women marrying. Notably, rural Georgians approve 15% less than Tbilisians. This question may be related to rural support of the moratorium. Although the CB 2013 does not ask whether respondents would like to have foreign neighbors, presumably rural inhabitants would be less likely to want foreign neighbors if they are unlikely to support the marriage of a local woman to a foreigner.

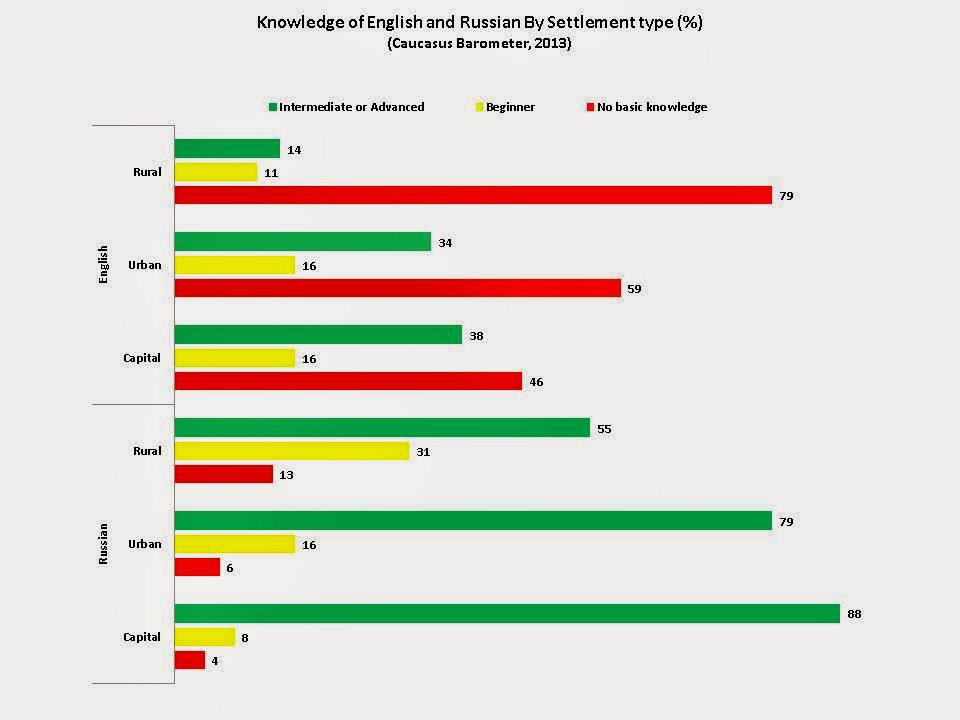

An additional factor to consider is that rural residents are much less likely to speak a foreign language compared to urban or capital based residents. The majority of rural Georgians (80%) report having no basic knowledge of English compared to 46% of Tbilisi’s residents reporting no basic knowledge of English. Furthermore, 44% of rural residents report having either no basic knowledge or a beginner’s level of Russian, compared to 12% of Tbilisi residents who say the same.

Note: Responses of Intermediate and Advanced were combined in this graph.

With the language barrier, it could be difficult for Georgian and foreign farmers to form relationships and communicate effectively. In order to avoid the language barrier, a number of companies have brought their own labor force to the country, including the Xinjiang Hualing Group which operates a small factory town on the outskirts of Kutaisi. Despite this, many foreign farmers who have moved to Georgia report hiring Georgians, especially during the harvest season. This could be a further factor which has conditioned the relationships existing between local and foreign farmers, as well as future relations between them.

This blog post has looked at the perspectives of rural residents on doing business with members of other ethnic groups as well as their level of knowledge of English and Russian. It shows that rural Georgians are much less likely to approve of doing business with other ethnicities, and that rural residents are much less likely to have knowledge of Russian or English. With these factors in mind, support for the ban on agricultural land sales may be more understandable. If residents in rural areas, many of whom are involved in agriculture, are less likely to be able to communicate with foreigners and are more likely than other Georgians to disapprove of relationships with them, then would they want them as neighbors? To explore these issues further, we recommend using our ODA tool here or reading this blog post detailing the extent of foreign agricultural holdings posted on the Transparency International Georgia website.

Posted by

Dustin Gilbreath

at

9:03 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Foreign Direct Investment, Georgia, Law, Transparency International

Wednesday, February 02, 2011

Observations while Traveling through Samegrelo | Agriculture and Petty Crime

The reasons are also familiar: privatization separated the land into small parcels that were not viable for modern farming. The people left in the countryside often are conservative and skeptical, and not quick to adopt more productive methods. They do not cooperate, and thus cannot mobilize sufficient resources to develop their land.

Traveling through Samegrelo recently highlighted another challenge. The structure of landholdings makes them particularly vulnerable to petty crime. Often the holdings are away from people's houses, so that they cannot guard them. During planting season seeds, seedlings and little plants can be stolen from the field at night, so that investing into better plants is not very attractive. Moreover, shepherds don't always respect fields that have just been fenced off anew, and let their cows trott into enclosures; or cut the fence to let a stray cow out, without repairing it.

During harvest season, the problem is even more pronounced. Unless you harvest early, your crop is at threat. And if you harvest early, you may be doing damage to the fruit. For some of the crop, the harvest season is quite long, so that the fields remain vulnerable over several weeks.

If you have a small holding, it is hard to address this problem. Sleeping outdoors on your field will only get you so far, and is not sustainable over time. With average landholdings being around less than two hectares (one hectare being a bit bigger than a soccer field), the plots are too small to pay for a security guard. Typically you will need two guards, so that they can support each other. Professional security firms would charge up to $1,000 per month. This makes it particularly difficult to experiment with higher value crops (say, avocado) since you may need a security guard to protect a handful of plants. Easier to fall back on what you have always done.

|

| Planting in Samegrelo. This effort has fences, two security guards constantly, night vision goggles, and is about to add a trained guard dog. |

We are curious whether other people have heard about this problem. If it indeed appears to be a challenge, it would be worth researching this in more detail. The government could help address this issue by providing more security through increased policing and curbing road access, together with introducing stiff sentences to signal that stopping agricultural theft is important for Georgia's economic development. Comments and ideas?

Posted by

HansG

at

3:32 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Law

Saturday, February 17, 2007

Cows in the Caucasus: overgrazing, underfed

How do we get a measure on what's happening with agriculture? It turns out that dairy farming provides powerful indicators. According to an IFC expert, the average Georgian cow yields 1000 liters of milk per year. By comparison, a wholesome Swedish cow can provide up to 9000 liters.

Intensive Western farming practices may not be a desirable model -- they require investment, expertise, and bring their own perverse results. Nor can practices be transplanted: under current circumstances, the expert said, a Holsten cow in Georgia simply would not survive.

But the status quo is not sustainable either. There are an estimated 700.000 cows in Georgia, severely overgrazing the pastures (together with the sheep, and overall numbers are growing). It is a classic example of the tragedy of the commons: a free resource for which there is unlimited appetite eventually gets exploited beyond carrying capacity. In the Caucasus overgrazing leads to desertification and erosion, while also destroying the habitat of other species.

If properly fed and kept, the average Georgian cow could provide 4000 liters. What is missing? Expertise is in short supply, and so much farming is subsistence-based that it is difficult to introduce better practices. Cows themselves count as capital, so farmers don't think much about increasing the productivity of individual cows, but rather want to have more of them. Larger dairy farms are very rare. Nor are the cows bred systematically. Investment would be required, but there is little capital. One of the problems is also that milk powder, subsidized by the European Union, apparently is smuggled in from Russia and makes dairy farming uncompetitive (many locally-made milk products actually are made from EU milk powder, rather than from local milk).

Land reform may be one solution, but there is little political appetite for it. In the meantime, various organizations are working with farmers to bring more expertise. Fortunately, it is easy to demonstrate the impact of better practices, so some farmers are catching on.

Posted by

HansG

at

11:07 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Farming, Land Management, Land Reform

Monday, December 18, 2006

Barriers to Cooperative Ventures in Rural Georgia: Feisty Farmers

Much has been made about the collapse of agriculture in

The international community and increasingly the Georgian government itself have been asking how successful agricultural ventures can be increased throughout

Baramidze found that in rural communities of

The researcher highlighted five main barriers hindering co-op developments in rural areas of Georgia: 1) peasants and small-scale farmers are unfamiliar with the benefits of cooperation; 2) farmers are not educated about the principles of community resource management; 3) there is no concrete plan for the development of small farm cooperative markets in rural communities; 4) villagers distrust each other too much to cooperate; 5) a lack of financing exists for agricultural development.

In order to improve co-op development in rural areas, Baramidze suggests developing cooperative management training materials based on recommendations developed by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and Credit Agricole and adopting them to the local Georgian environment taking into consideration aspects of Georgian cooperative heritage – soviet farms (kolkhoz) and Georgian co-ops that existed before the Soviet revolutions in 1917 and 1921 – that may still be useful in contemporary Georgia. Moreover, Baramidze suggests incorporating the best types of social interactions of communities existing in rural

The idea of using traditional practices and incorporating them into modern democratic traditions is an exercise most certainly worth further consideration.

Posted by

AaronE

at

4:26 PM

7

comments

![]()

Labels: Agriculture, Alaverdi, Community Management, Cooperatives, CRRC Fellowship, Farming, Georgia, Land Management, Land Reform, West Georgia