[Note: This article was published in partnership with OC-Media, here. The article was written by Dustin Gilbreath, Deputy Research Director at CRRC Georgia. The views presented in this article do not represent the views of UN Women, CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.]

Widely condemned as a violation of human rights, child marriage is associated with negative health outcomes — both physical and psychological. Aside from these clear issues, a growing body of research suggests child marriage also has economic consequences for both the women who marry under the age of 18 and society at large.

A policy brief released by CRRC Georgia today shows that child marriage remains a persistent problem in Georgia for both ethnic Georgians and ethnic minorities and that it comes with significant economic consequences. Yet, the brief also suggests that interventions in the education system have the potential to alleviate the economic harm of child marriage.

The child marriage rate in Georgia has remained static over the years. Data from a UN Women study on women’s economic inactivity suggests that the share of women who have ever married in the country who did so when they were under the age of 18 has not changed beyond the margin of error over the decades.

In the 2010s, the survey suggests 14% of women who ever married did so before turning 18, the same share as in the 1950s and earlier. This finding falls in line with UNICEF’s most recent estimate of the early marriage rate in Georgia.

Still, it likely underestimates the extent of the issue to a certain extent, since people under the age of 18 at the time of the survey were not interviewed.

The data suggest that child marriage is a particularly acute problem in rural areas, with 21% of rural women who have ever married having done so under the age of 18. This is a rate twice as high as in Tbilisi (9%) and other urban areas (10%).

The study is, however, inconclusive when it comes to child marriage rates among ethnic minorities (10%) compared with ethnic Georgians (9%). This likely stems from the relatively small number of ethnic minorities within the survey; other studies have found much higher rates among Georgia’s ethnic minorities, particularly the country’s ethnic Azerbaijani population.

This finding does, however, underline the point that child marriage is not just a problem among ethnic minorities in Georgia — but also among ethnic Georgians.

The costs of child marriage

Using data from CRRC Georgia, Swiss Development Cooperation, and UN Women, I statistically matched the group of women who had married early to a group who had not but came from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. Using this matched sample, it was possible to estimate the effects of child marriage on women’s economic and educational outcomes.

The results showed that women who married under the age of 18 earned 35% less than those from similar backgrounds who did not marry as children. Moreover, they were significantly less likely to participate in the labour force.

This is in a context where women already make significantly less and participate in the labour force at significantly lower rates than men.

Educational attainment was also significantly lower among the women who married before turning 18. The women in the matched sample who married underage were 2.3 times less likely to attain a higher education than those who married later in life.

Similarly, women who married as adults were six percentage points more likely to obtain a vocational education than those who married as children.

Two-thirds of women who married under the age of 18 (64%) obtained only secondary or lower levels of education, compared with 36% of women from similar socioeconomic backgrounds who married as adults.

However, the study suggests that when women who marry under 18 attain similar levels of education as those who marry as adults, the differences in outcomes largely disappear.

The women who married as children and those who married above the age of 18 in the matched sample who had the same levels of education earned statistically indistinguishable amounts. They also participated in the labour force at similar rates.

This finding suggests clear paths to alleviating the economic harm that child marriage causes in Georgia. By supporting girls who marry under 18 to stay in and complete school, encouraging those who have left to return, and creating an enabling environment for both groups, the economic harm of child marriage could be reduced.

Child marriage has clear social, psychological, and health consequences. These matter more than, and likely contribute to, the economic consequences described above.

While the ultimate goal of policy on child marriage in Georgia should be ending it, until that time, reducing the economic harm it causes should also be a goal. The data suggest that educational interventions are potentially a beneficial place to start.

The data and replication code of its analysis are available here.

Monday, January 20, 2020

The economic and educational consequences of child marriage in Georgia

Posted by

CRRC

at

4:25 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economic Situation, Education, Gender, Marriage, Sex

Wednesday, October 02, 2019

Public Opinion in Georgia on Premarital Sex for Women

Conservative traditions are deeply rooted in Georgian society, particularly when it comes to premarital sex. The 2019 Knowledge and Attitudes towards the EU in Georgia Survey, which CRRC Georgia carried out in partnership with Europe Foundation, shows that as in the past waves of the survey, people think that it is more justified for men than women to have pre-marital sex. Between the 2017 and 2019 waves of the survey, the shares of people thinking it is justified has not changed significantly.

To explore the issue in greater depth, read this blog post which breaks down the demographics on attitudes using the 2017 wave of the survey or look at the data using our Online Data Analysis tool.

Posted by

CRRC

at

1:21 PM

0

comments

![]()

Monday, March 12, 2018

Dissecting Attitudes towards Pre-Marital Sex in Georgia

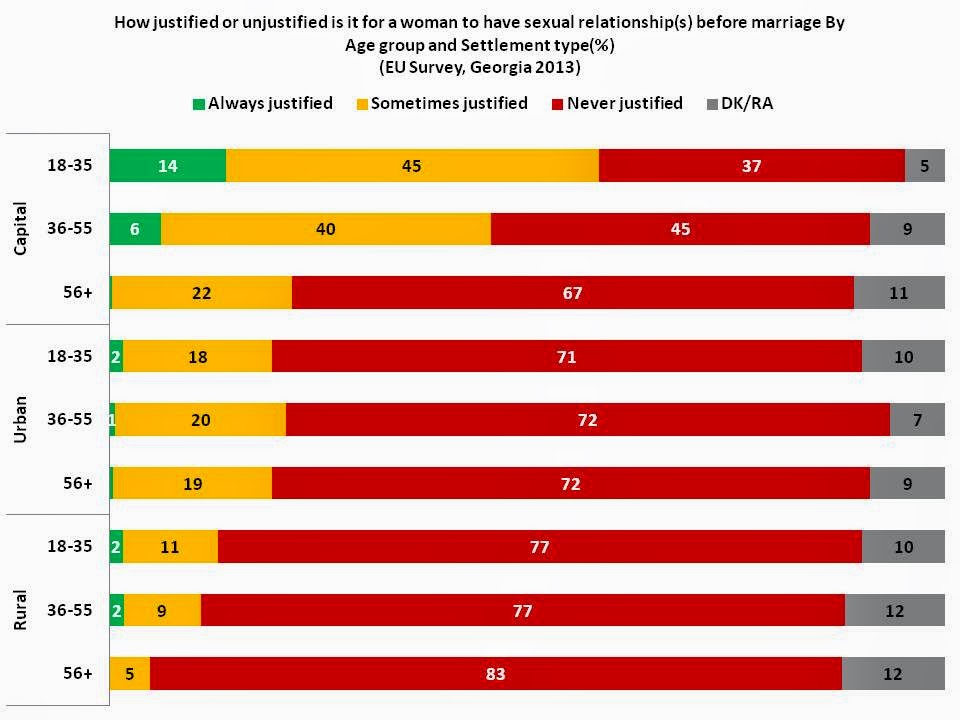

Many in Georgia embrace conservative attitudes about premarital sex, as a previous CRRC blog post highlighted. Attitudes are different, however, depending whether it’s a male or a female having the premarital relationship. This blog post uses data from CRRC’s 2017 Knowledge of and attitudes toward the EU in Georgia survey (EU survey) conducted for Europe Foundation to describe how justified or unjustified people of varying ages, genders, and those living in different types of settlements believe pre-marital sex to be for men and women.

In 2017, when asked, “In your opinion, how justified or unjustified is it for a woman to have a sexual relationship before marriage?” 71% of people in Georgia reported that it is ‘never justified.’ In contrast, only 38% responded that it is ‘never justified’ for a man to have a sexual relationship before marriage. Both men and women are more conservative towards women engaging in pre-marital sexual relationships than men. However, women report that it is ‘never justified’ for a man to have pre-marital sex slightly more often than men.

Variations in the level of justification of male and female pre-marital sex can also be observed by age group and settlement type. Unsurprisingly, older people (56+) hold more conservative attitudes toward pre-marital sex than younger individuals, responding more frequently that it is ‘never justified’ for both men and women to have a sexual relationship before marriage. Nonetheless, people above the age of 55 exhibit much greater acceptance of a man having a sexual relationship before marriage than of a woman.

Both men and women in the capital and other urban settlements are more liberal than those residing in rural and ethnic minority settlements. However, men and women in Tbilisi generally demonstrate greater acceptance of premarital sex than those in other urban settlements of Georgia. While people living in rural and ethnic minority settlements hold the most conservative attitudes in general, they are more strongly opposed to women having pre-marital sexual relationships than men, further highlighting how standards of ‘justifiable’ sexual behavior are applied to men and women differently.

The data presented in this blog post highlights a number of findings. First, a majority of individuals in Georgia believe that women should adhere to conservative standards of sexual ‘purity,’ while men are granted greater liberty in this regard. Secondly, even within populations that are more liberal toward pre-marital sex — men and women aged 18-35 and those residing in the capital — most people still report it is never justified for a woman have a pre-marital sexual relationship, while they are more liberal with men. The fact that women tend to respond more frequently that it is ‘never justified’ for a woman to have a pre-marital sexual relationship than responding the same about a man demonstrates the extent to which women have internalized gendered norms regarding sexual behavior.

To explore the data used in this blog post further, visit our Online Data Analysis platform.

Monday, February 02, 2015

Premarital sex and women in Georgia

Conservative traditions have always been strong in Georgian society, and especially so when it comes to relationships. Nonetheless, men are often allowed and even encouraged to engage in premarital sex, while it is usually considered unacceptable for women. Using data from the survey Knowledge and attitudes towards the EU in Georgia (EU Survey) funded by the Eurasia Partnership Foundation and conducted by CRRC-Georgia in 2009, 2011 and 2013, this blog post looks at who reports more liberal views in regard to premarital sex in Georgia – men or women – and whether there are any differences in attitudes based on respondent age, level of education, or settlement type.

Attitudes towards premarital sex are changing in Georgia. In 2009, when asked, “How justified or unjustified is it for a woman to have sex before marriage?” 78% of Georgians reported that it is never justified. In 2013, 69% reported the same. In contrast, a much lower share of the population thinks that premarital sex is never justified for men – 39% in 2013, slightly up from 33% in 2011.

While dominant values, religion, and patriarchy engender many stereotypes about gender in Georgia, women also play an important role in maintaining them. A slightly higher percentage of women than men reported in 2011 that it is never justified for women to have premarital sex (70% and 58% respectively) while in 2013 and 2009 the percentages are almost equal.

Counter-intuitively, the younger generation (18-35 year olds) in Georgia disapproves of premarital sex for women to almost the same extent as older generations. As shown in the chart below, 18-35 year old Georgians are nearly as likely as 36-55 year olds to report that it is never justified for women to have sex before marriage. The youngest age group, however, is slightly less likely to report disapproval compared with Georgians who are 56 years old and older.

Residents of the capital are the least conservative on this issue, but rates of disapproval have declined both in and outside the capital since 2009. In 2013, only 48% of Tbilisians thought that premarital sex was never justified for women compared with 65% in 2009. In non-capital urban settlements, disapproval declined slightly from 83% in 2009 to 71% in 2013. Rural residents are the most conservative, with 79% thinking that premarital sex for women should never be justified in 2013, but some change can be seen over the years in rural settlements as well – in 2011 and 2009, 88% of rural residents reported that women having premarital sex is never justified.

Education also plays a role in forming Georgians’ attitudes towards controversial issues. In 2013, 63% of those with higher education believed that premarital sex was never justified for women, while 81% of those with secondary technical and 84% of those with secondary or lower education reported the same.

To sum up, level of education, age and settlement type are important to consider when examining Georgians’ attitudes towards premarital sex. Although Georgians generally disapprove of women having premarital sex, attitudes appear to be changing.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:48 AM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Gender, Georgia, Marriage, Sex, South Caucasus

Monday, June 09, 2014

Divorce rates in Azerbaijan

In the Principles and Recommendations for a Vital Statistics System, Revision 2 (by the United Nations), divorce is defined as “a final legal dissolution of a marriage, that is, that separation of husband and wife which confers on the parties the right to remarriage under civil, religious and/or other provisions, according to the laws of each country.” This blog post examines divorce in Azerbaijan over the years, by age group, gender and by duration of marriage. The post also explores perceptions of happiness among divorced Azerbaijanis and those who are not divorced.

Attitudes towards divorce in Azerbaijan are predominantly negative. According to the Caucasus Barometer 2013 (CB), almost half of Azerbaijanis feel that divorce can never be justified (48%).

When compared to many other countries in the world, the divorce rate in Azerbaijan is relatively low. According to the United Nations' Demographic Yearbook, the highest number of divorces in the world can be observed in Russia (4.7 per 1,000 people in 2011), Belarus (4.1 in 2012), Latvia (3.6 in 2012), Lithuania (3.3 in 2012), Moldova (3.0 in 2012), Denmark (2.8 in 2012), and the United States (2.8 in 2011). In comparison, that rate in Azerbiajan is 1.2 per 1,000 people (in 2012).

Data provided by the State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan (AzStat) shows that the number of divorces has decreased in Azerbaijan overall from 1990 to 2008, followed by a gradual increase from 2008.

The 2013 Caucasus Barometer (CB) shows that women who are divorced or widowed tend to say they are less happy than men who are divorced or widowed. In Azerbaijani society, divorced females and widows suffer from a great deal of insecurity and instability, especially since the stigma about divorce is large.

If you are interested in further exploring these issues or would like more information, see the Caucasus Barometer website here.

By Aynur Ramazanova

Posted by

Dustin Gilbreath

at

9:24 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, Divorce, Gender, Marriage

Monday, April 07, 2014

Happiness in Georgia

Happiness is an issue that has been the subject of philosophical and social science reflection at least since the ancient Greek philosopher Democratis (460 BC -370 BC) said, “Happiness resides not in possessions, and not in gold, happiness dwells in the soul.” This oft cited sentiment frequently comes with the suggestion that home and family are more important than material wealth. This blog post will take a look at these sentiments and examine how happiness relates to personal income, settlement type, and marital status in Georgia.

Economists have been debating whether money can “buy” happiness for decades, if not centuries. Douglas J. Den Uyl and Douglas B. Ramussen in their 2010 article have argued that Adam Smith, author of the famed book, The Wealth of Nations “was the first ‘happiness’ theorist in economics.” Interestingly, the 2013 Caucasus Barometer shows that in Georgia, individuals with higher incomes are also more likely to say they are happy.

Although self perceptions of happiness in Georgia appear to increase with personal income, the Easterlin Paradox holds that happiness will increase with income, but only up to the point where needs and wants are met, and where having more money becomes superfluous. Judging whether the Easterlin Paradox applies in Georgia is not possible from an examination of data from the Caucasus Barometer. However, Lia Tsuladze, Marine Chitashvili , Nani Bendeliani , and Luiza Arutinovi write more about income, economics and happiness in their 2013 article.

Settlement type also seems to be related to how happy Georgians consider themselves to be. Georgians living in urban areas (66%), including Tbilisi (67%), are more likely to consider themselves to be happy than those living in rural areas (56%).

Marital status is a third factor related to happiness in Georgia. Alfred Lord Tennyson's 1850 poem, In Memoriam: 27, states, “Tis better to have loved and lost/ Than never to have loved at all.” Despite these lines’ continued prominence today, at least in Georgia, it appears that it is better to have loved and not lost, or to have never loved at all. Georgian widows, widowers, the separated and divorced report being unhappy more than twice as much as Georgians who are married, cohabiting or who were never married.

Personal income, where one lives, and marital status appear to be related to perceptions of happiness in Georgia. We encourage you to explore the data further using our ODA tool. We also recommend reading this blog post which examines happiness in Azerbaijan.

Posted by

Dustin Gilbreath

at

8:54 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economic Situation, Georgia, happiness, Marriage, Settlement

Monday, March 24, 2014

Aspects of Georgian Nationalism

In Stephen Jones’ 2013 book, Georgia: A Political History since Independence, he argues that economic issues are more important to the average Georgian than issues related to nationalism. According to Benedict Anderson’s classic exegesis of nationalism, Imagined Communities, a nation is defined as, “an imagined political community - and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign” (Anderson 2006). Anderson’s definition, in this blog post, is considered in conjunction with the oft quoted expression of Ilia Chavchavadze, “Homeland, Language, and Faith,” which referred to those things most important for Georgia in his view. As such, issues Georgians believe to be the most important issue facing the country over time and how Georgians feel about Georgian women marrying men of other ethnic groups are examined to gain an understanding about some aspects of nationalism in Georgia.

Each year the Caucasus Barometer (CB) asks (as an open-ended question), “What do you think is the most important issue facing Georgia at the moment?” The following graph shows that the only time territorial integrity, relations with Russia and peace have been more important than jobs and poverty in Georgia was in 2008 which was also the year of the August war with Russia. Notably, data collection for the 2008 CB was conducted only three months after the war. Furthermore, only one year later, economic considerations once again became the number one perceived issue facing the country. Considering that territorial sovereignty is considered to be a critical aspect of nationalism, it is interesting that Georgians have been more likely to consider economic issues to be the most important issue facing the country rather than issues related to territorial integrity.

A second way of assessing how Georgians feel about other ethnicities, is to examine to what extent Georgians approve or disapprove of Georgian women marrying members of other ethnic groups. The graph below shows that most Georgians do not support Georgian women marrying men of other ethnicities. This shows a certain level of social conservatism among Georgians, but this conservatism may be religious rather than ethnic as nationalism in Georgia is also tied to religion. The graph shows that Georgians have the highest level of approval for Georgian women marrying men of other ethnic groups that primarily tend to be Orthodox or another Christian group - Russians, Europeans, Americans, Abkhazians, Ossetians and Armenians.

This blog post has looked at several factors related to Georgian nationalism. It shows that economic issues have been consistently more important to Georgians than issues related to territorial integrity since 2008--a year which saw war with Russia. Finally, the blog looked at trends in how Georgians feel about Georgian women marrying men of other ethnicities and found that religion might play a bigger role than ethnicity when it comes to marriage.

To further explore issues related to nationalism, ethnicity, and economics we recommend exploring our data further using the ODA tool here, or reading Stephen Jones’ chapter on “The Myth of Georgian Nationalism.” For readers who read in the Georgian language, we also recommend this blog post on tolerance in Georgia and the South Caucasus more generally.

Posted by

Dustin Gilbreath

at

9:24 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economy, Georgia, Marriage, Nationality

Friday, December 20, 2013

Attitudes towards Europeans and Americans among Georgian Youth

On November 29, Georgia initialed an Association Agreement with the European Union at the EU-Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius, Latvia. This represents a step toward closer economic integration of Georgia into the EU. According to CRRC’s 2012 Caucasus Barometer (CB), 72% of Georgians fully or rather support Georgia’s membership to the EU, and 67% of Georgians fully or rather support membership in NATO. This would imply that Georgians have generally positive attitudes towards a political and security-based relationship with the West (i.e. EU and the United States). In addition, 59% of Georgians (especially those between 18-35 years old) agree with the statement, “I am Georgian, and therefore I am European.” Using data from the CB 2012, this blog shows that positive attitudes towards Americans and certain Europeans, such as the English and Greeks, are higher among Georgian youth.

Overall, Georgians have positive attitudes towards doing business with Americans, the English and Greeks. 79% of Georgians approve of doing business with Americans. 77% feel the same with respect to the English and 75% with Greeks. When split by age groups, approval is highest among Georgians 18-35 years old for all three nationalities. For example, doing business with Greeks has 80% approval among 18-35 year olds, 76% among 36-55 year olds, and 70% for those 56+. Approval for doing business with Americans and English follows a relatively similar trend.

Socially, approval of Georgian women marrying foreign men is relatively low (36% for Americans, 36% for the English and 35% for Greeks). However, younger Georgians are slightly more open to Georgian women marrying within these groups, than Georgians 56 years and older.

When it comes to politics, young Georgians are also more trusting of the EU, which is not surprising since 67% of Georgians between 18-35 years old see themselves as European. A caveat in these responses is that 12% of Georgians believe that Georgia is currently a member of the EU, including 17% of those aged 18-35 years old (CRRC EU Survey 2011, Georgia).

In line with their greater trust of the EU and approval of doing business with Americans, slightly more young Georgians believe that the United States is the biggest friend of Georgia, than older Georgians. In contrast, 41% of young Georgians (18-35 years old) believe that Russia is the biggest enemy of Georgia, whereas 32% of all Georgians 36 and older agree.

Younger Georgians, 18-35 years old, appear to show slightly higher approval of cooperation with the West on these specific questions. The same trends of approval exist with respect to knowledge of English and personal income. That is, in Georgia, higher levels of education, knowledge of English, and personal income are related to higher rates of approval for certain Europeans such as English and Greeks, and Americans with respect to the economic, social, and political aspects discussed above.

Posted by

Anonymous

at

9:16 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Attitudes, Business, English, European Union, Georgia, Greece, Marriage, Trust

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Georgia: A Liberal or Socially Conservative Country?

Monday, August 15, 2011

Intermarriage in the South Caucasus

Posted by

Nikola

at

11:43 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Attitudes, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Marriage

Wednesday, April 06, 2011

Caucasus Barometer 2010 reveals Georgian attitudes towards Indians

Posted by

Shefali

at

9:53 PM

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, February 24, 2011

Sex, Lies and EU Red Tape

Respondents were asked whether a range of these controversial activities were either ‘never justified’, ‘sometimes justified’ or ‘always justified’. Breaking down responses according to respondents from households that reported having a member who had lived in the EU for three months or more since 1993, against those from households that had no such members uncovered an interesting trend.

For example, respondents were asked whether it was ever justified for a woman to have a sexual relationship before marriage. A full 80% of respondents who had no family member who had lived in the EU reported that this was ‘never justified’, whereas only 54% of those with a family member who had lived in the EU felt the same. In terms of whether this was ‘sometimes justified’ the figures stood at 13% and 28% respectively (see table below).

A similar trend was found for attitudes to childbirth outside wedlock, as well as extra-marital affairs for both women and men. Meanwhile, though hardly anyone felt homosexuality was ‘always justified’, 10% of those with a household member who had lived in the EU felt it was ‘sometimes justified’ against only 3% of those who had no such member (see table below).

Interestingly, the same trend in attitudes held concerning such negative phenomena as lying, tax-avoidance, using criminal authorities for dispute resolution, and purchasing stolen goods. For example, while 69% of those respondents from households with no family connection to the EU feel lying for personal benefit is ‘never justified,’ only 57% of those with EU-experienced household members think the same (see table below).

If it is true that people-to-people contact creates shifts in attitudes, then a family member who has lived in the EU might ‘import’ certain value orientations into some households creating the differences manifested in the survey.

Given this, the question remains: why should having contact with someone who has lived in the EU affect individual liberalism in attitudes towards sexual matters, yet apparently negatively affect responsible social attitudes towards honesty, tax-paying, and rule of law? Is the EU a force for moral disorientation?

In answer to this, we should note that the survey does not ask if the practices in question are morally good or bad. Instead, it asks whether there might be some situations where such practices are justified. Plausibly then, those with exposure to predominantly tolerant, liberal and more relativistic values in Europe might be expected to produce flexible responses in which controversial practices are not categorically rejected on the basis of absolute moral beliefs.

So finally, perhaps we might suppose that as Georgia increases people-to-people contact through educational programs, political cooperation and trade, Georgians could slowly move towards a philosophy of ‘live and let live’.

Posted by

Gavin Slade

at

3:08 PM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Attitudes, European Union, Georgia, Lies, Marriage, Sex