Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dustin Gilbreath, a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, the Council of Europe, or any related entity.

Overall, according to the survey — which CRRC Georgia conducted for the Council of Europe — 8% of the public reported knowing an LGBT person, and 87% reported they did not. A further 5% were uncertain, and 1% refused to answer.

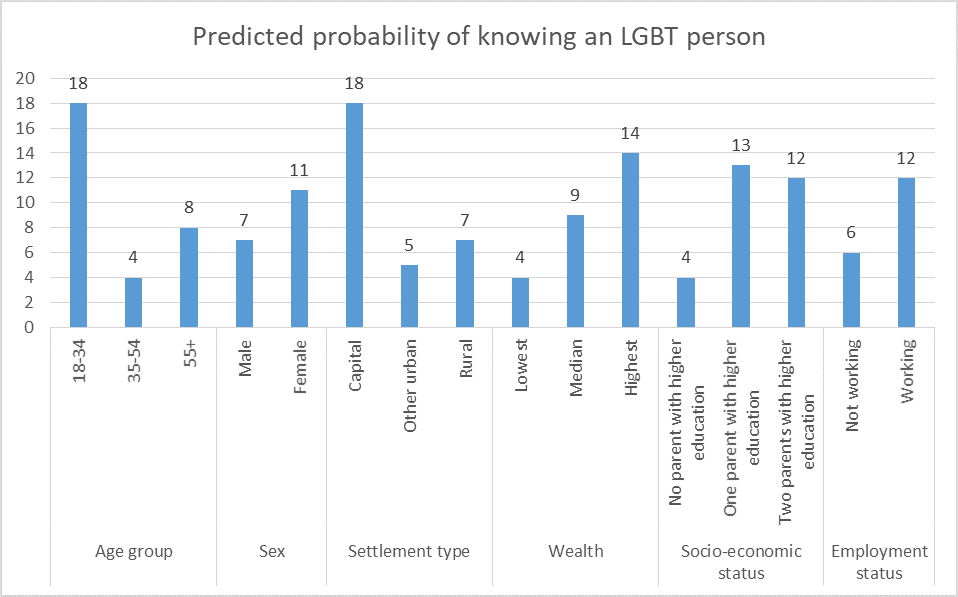

The data shows young people are significantly more likely to know an LGBT person. So are people in Tbilisi, wealthier people, people who are employed, and those with a higher socio-economic status. Women are slightly more likely to report knowing an LGBT person than men. Ethnic minorities, those with different levels of education, IDPs, and people with children in their household are no more or less likely to report knowing an LGBT person than ethnic Georgians, non-IDPs, and those without children in their households.

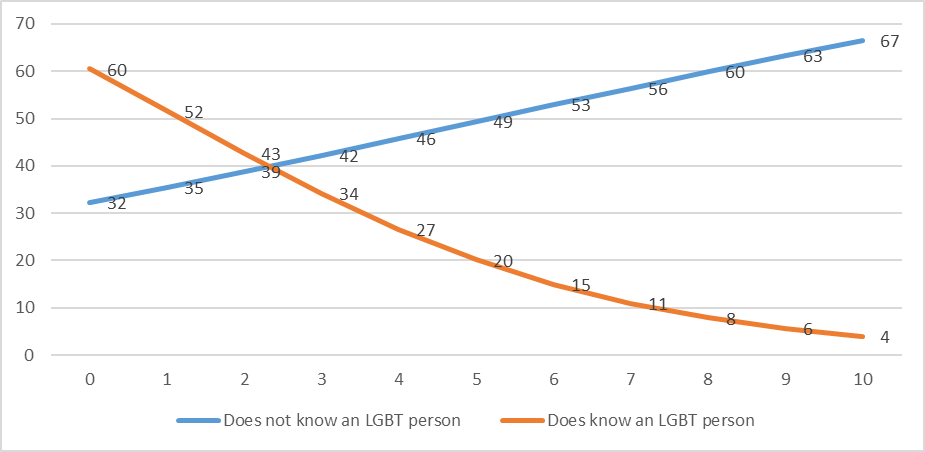

To understand whether people who know an LGBT person are also more tolerant of LGBT people in general, a matching analysis was conducted. This method identifies statistically similar people who know and do not know an LGBT person and then compares their attitudes. The goal is to understand whether knowing an LGBT person might also be associated with tolerance for LGBT people more broadly.

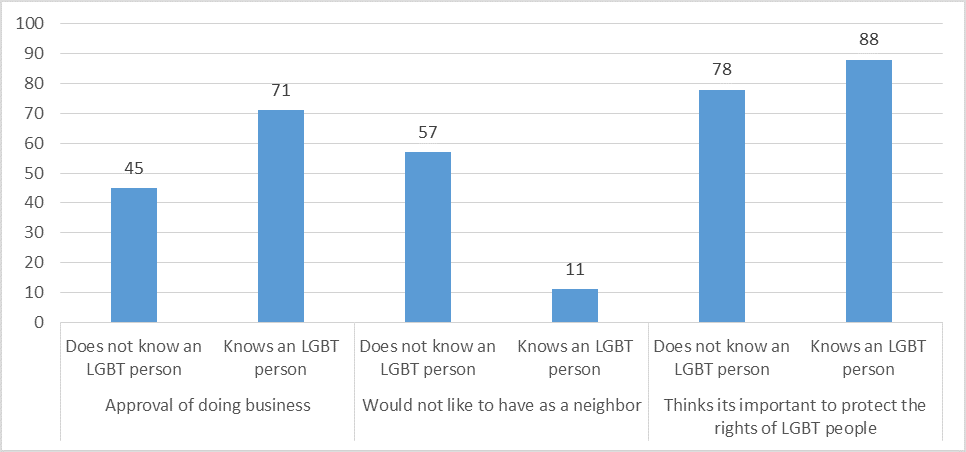

The analysis shows that people who know LGBT people are significantly more tolerant.

People who know an LGBT person are 26 percentage points more likely to approve of someone like them doing business with a homosexual person, compared with those who have otherwise statistically similar demographic characteristics. They are 10 percentage points more likely to think it is important to protect the rights of LGBT people. People who know an LGBT person are 46 percentage points less likely to say they would not want an LGBT person as a neighbour.

The effect of knowing someone who is not a heterosexual varies significantly with a number of social and demographic characteristics with regard to approval of doing business and approval of having an LGBT neighbour. However, it does not vary with regard to views on the importance of protecting the rights of LGBT people.

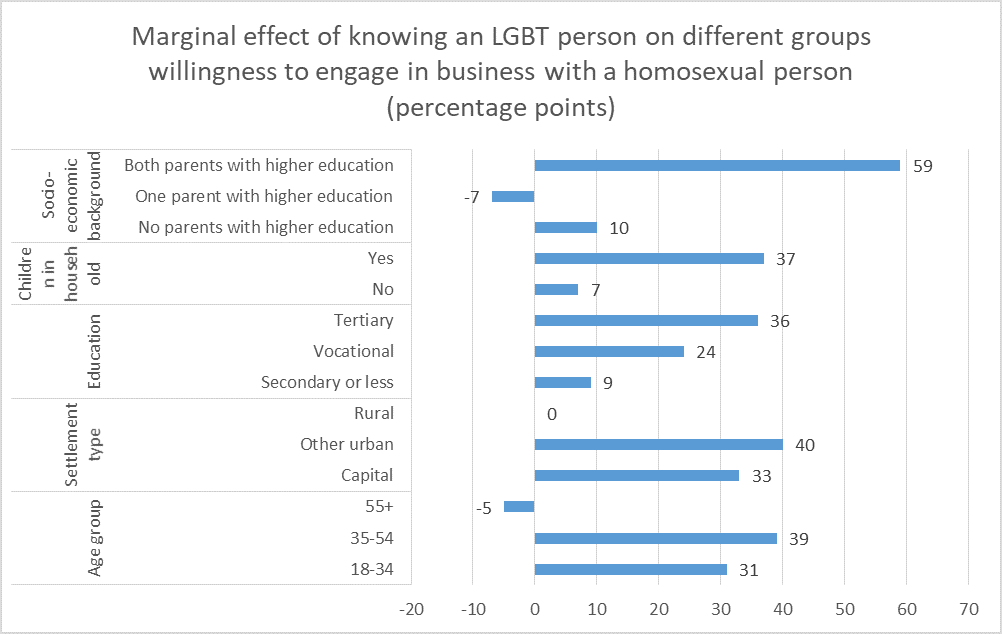

With regard to acceptance of doing business, the effect of knowing someone varies by age, settlement, wealth, socio-economic background, and whether or not a person lives in a household with children.

The data shows that the effect of knowing an LGBT person is particularly large for people with children at 37 percentage points, compared to only 7 percentage points for people without children.

The data also indicates that there is no effect in rural areas, while there are substantively large effects in urban areas.

The effect is also null for older people. By comparison, for people under the age of 54, the effect is rather larger at 39 percentage points for 35 to 54-year-olds and 31 percentage points for 18 to 34-year-olds.

The more education a person has, the greater the effect of knowing an LGBT person on their attitudes.

The data further shows that the effect is substantially larger for people from richer socio-economic backgrounds. To proxy people’s socio-economic backgrounds, the respondent’s parents’ education levels are considered, a common approach to understanding someone’s family background.

The effect of knowing someone is substantial if both of the respondent’s parents had higher education. In contrast, people with one or no parents with higher education experience little effect from knowing an LGBT person.

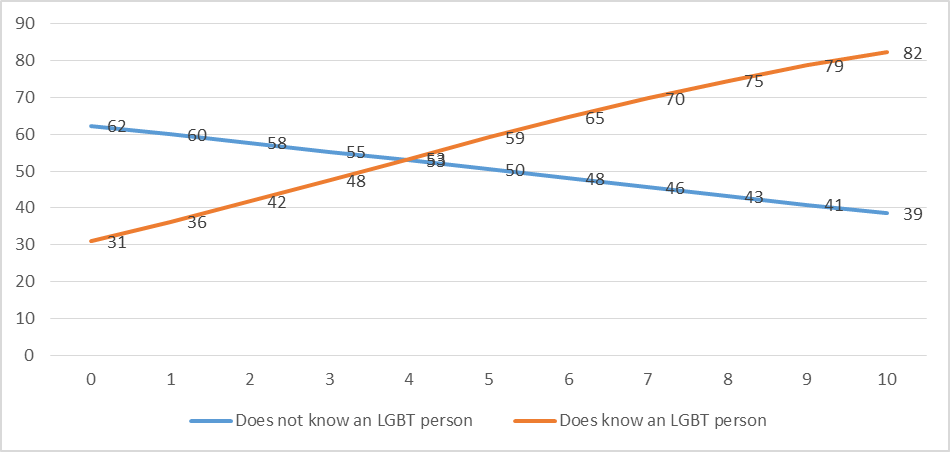

Current wealth also shows a striking pattern with regard to the impact of knowing an LGBT person. People living in poorer households are significantly less likely to approve of someone like them doing business with a homosexual if they know an LGBT person. In contrast, people living in wealthy households are significantly more likely to approve of someone like them doing business with a homosexual if they know an LGBT person.

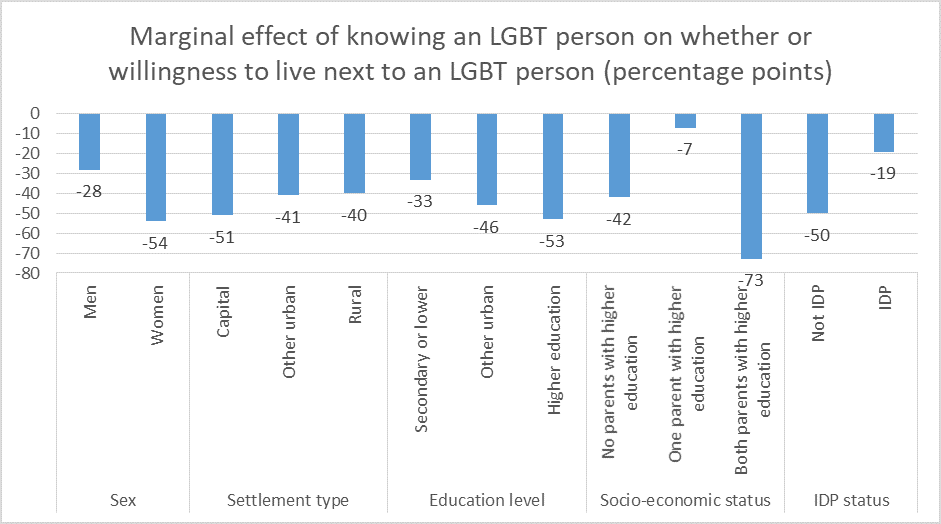

The size of the effect of knowing an LGBT person on willingness to live next to an LGBT person also varies with an individual’s sex, the settlement type they live in, their education level, whether or not they are an IDP, and their socio-economic status.

The effect is substantially larger for women than men (54 percentage points versus 28). The effect is larger in Tbilisi compared with other urban areas and rural areas. The effect is also larger for people with higher education and smaller for IDPs.

With regard to socio-economic status, the data shows that the effect is largest again for people with two parents that had higher education. People without parents that have higher education also experience a large effect. However, people with only one parent with higher education show no significant effect as a result of knowing someone who is LGBT on their willingness to live next to an LGBT person.

The data paint a similar picture of the effects on people in poorer and wealthier households of knowing an LGBT person on willingness to live next to an LGBT person. People in relatively well-off households are significantly more likely to be willing to live next to an LGBT person if they also know one. The reverse is true of people in poorer households.

In contrast to the willingness to do business with and to live next to an LGBT person, there were no significant variations in the size of the effect of knowing an LGBT person on different social and economic groups.

The above data calls for further research. While on average there are statistically significant and substantially large effects of knowing an LGBT person on average, the effects vary significantly between groups. People living in wealthy households and from relatively better-off backgrounds appear to respond strongest to knowing an LGBT person. Other groups also experience substantial impacts from meeting LGBT people. However, these tend to be relatively small. Future research should aim to understand the causal mechanism by which these impacts could take place.