Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Giorgi Babunashvili, a senior researcher at CRRC-Georgia and Anano Kipiani, a policy analyst at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity. This article is based on a paper, which was published in the International Journal of Sociology.

People’s values and attitudes are shaped by many factors, religion and historical experience being important among them.

A paper we recently published in the International Journal of Sociology suggests that Georgia’s communist past is associated with higher degrees of homophobia just as religiosity is.

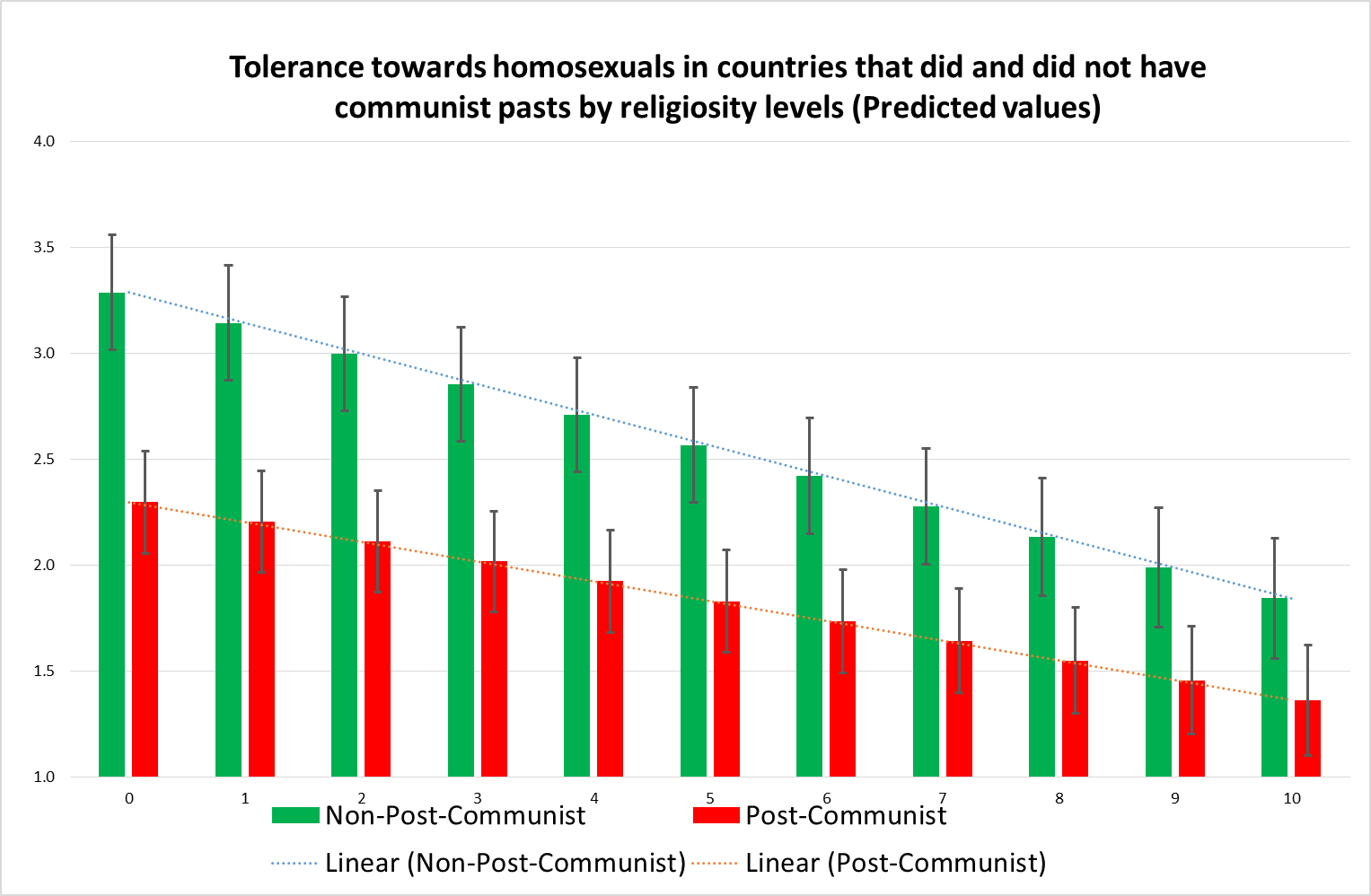

However, the experience of a communist past also moderates the impact of religiosity on homophobia. In post-Communist countries, an individual’s religiosity has a weaker effect on liberal attitudes toward same-sex relations than it has in countries with no communist government in their historical experience.

To show this, we used data collected between 2017 and 2020 in 17 countries through the International Social Survey Program (ISSP). The countries were selected to ensure that different religious denominations were present that both had and did not have a communist past.

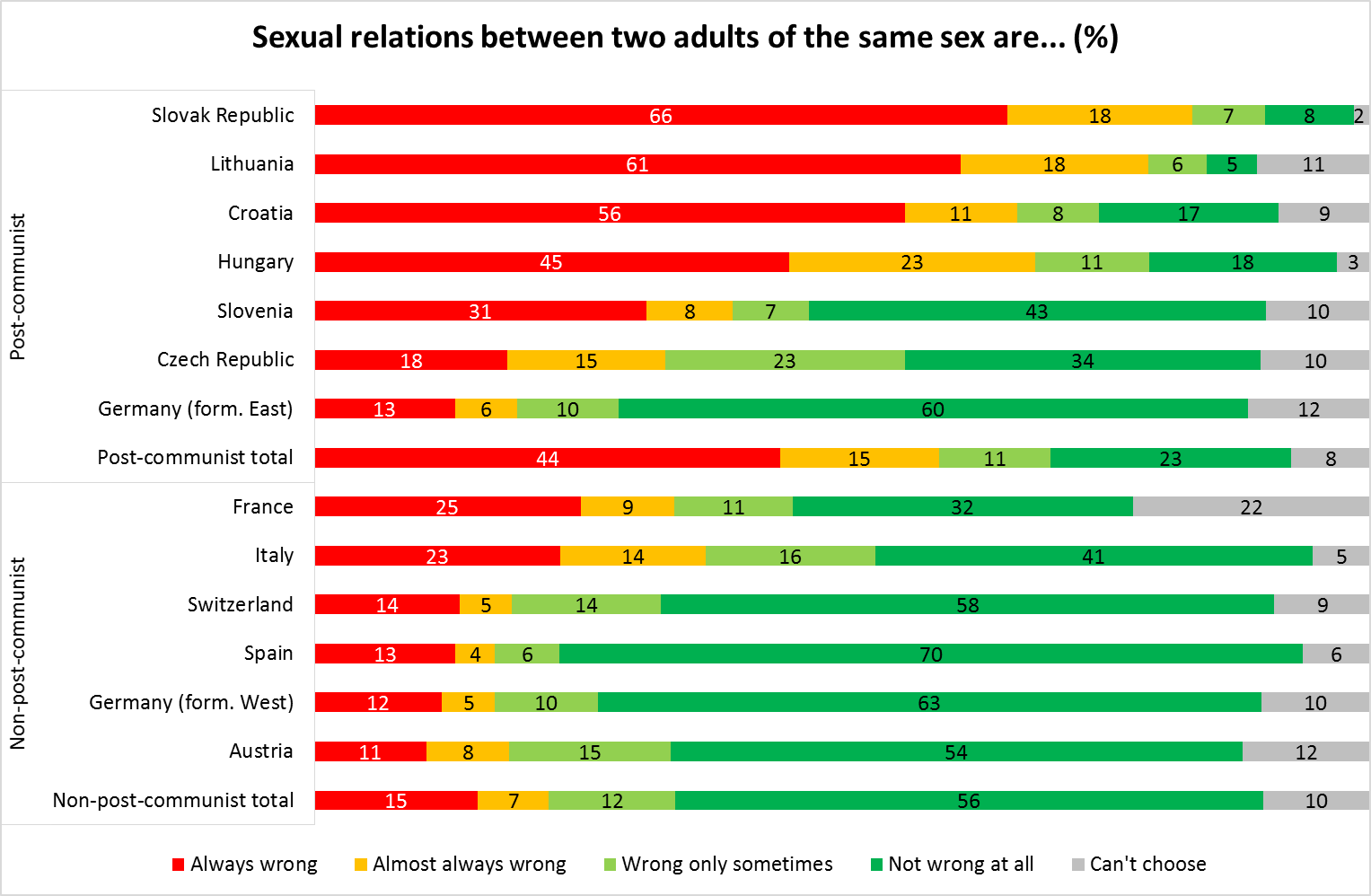

Under communism, same-sex relations were either illegal or treated as a psychological disorder. This may explain why post-communist societies are less tolerant towards same-sex relations. In the post-communist countries in the sample, 44% of people perceive sexual relations between two adults of the same sex as always wrong, in contrast to 15% in their non-post-communist counterparts.

Organised religion is often the dominant force against queer rights globally. A regression analysis shows that religiosity is an important factor affecting homophobic sentiments: a higher religiosity level is associated with lower tolerance of queer people.

Another important factor affecting tolerance towards queer people is society’s historical experience: individuals in post-communist countries are 0.6 points less tolerant on a four-point homosexuality-tolerance scale, compared to their counterparts in non-communist countries.

The effect of religiosity on homophobia is weaker in post-communist countries, where the difference in tolerance towards same-sex relations between the most and the least religious individuals is smaller compared to the similar difference in non-post-communist countries.

Thus, religiosity appears to encourage homophobia. So too does a communist past. While religiosity also drives homophobia in post-communist countries, it does so to a lesser extent. This appears to stem, in part, from people in post-communist countries being more homophobic across the spectrum of religiosity.