Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Giorgi BabunaSvili, Senior Policy Analyst, and Kristina Vacharadze, Programs Director at CRRC-Georgia, The views presented in the article are of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

Caucasus Barometer 2021 data shows that a majority of Armenians feel that the dissolution of the Soviet Union was bad for their country, while almost half of Georgians feel that the collapse had a positive impact on Georgia.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia and Armenia have shared differing yet similar paths.

Both have experienced wars, revolutions, and economic upheaval, but political direction and public sentiment on major political issues has often diverged.

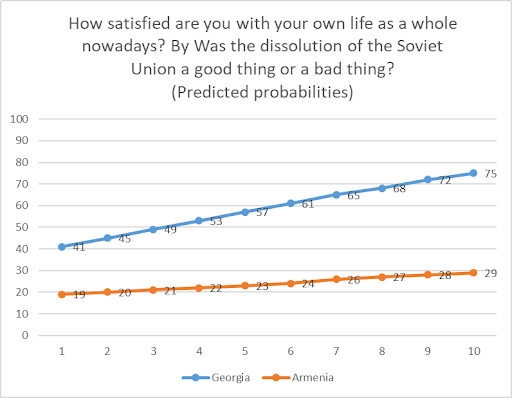

Data from the Caucasus Barometer 2021 has shown that a key difference is how the public views the Soviet collapse. In Armenia, a clear majority feels that the dissolution of the Soviet Union left the country worse off, while in Georgia opinion is divided, with half of the public viewing the collapse as having been good for the country.

The annual survey found that two thirds (67%) of Armenians think the dissolution was bad for the country, whereas around two in five (38%) in Georgia think the same. In contrast, almost half of Georgians think that this was a good thing for the country, while only about a fifth of Armenians agree with the statement.

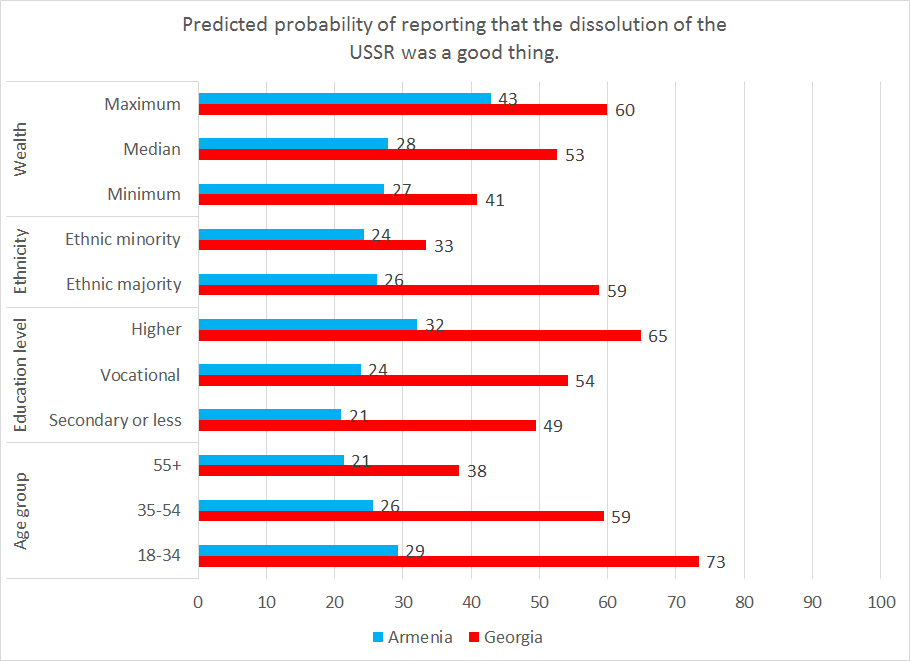

Opinions were associated with some demographic characteristics.

A regression model found that, in both Georgia and Armenia, people with a higher education were more likely to think that the dissolution of the USSR had had a positive impact than people with only a secondary or secondary technical education. In both countries, younger people were more inclined to say that the dissolution of the USSR was a good thing than older people.

There were no statistically significant differences in attitudes associated with gender, settlement type, or employment. However, wealth was a significant predictor of attitudes in Armenia: wealthier people assess the dissolution of the USSR more positively. The same variable was not statistically significant in Georgia.

Ethnic minorities in Georgia tended to feel less positively about the dissolution of the USSR than ethnic Georgians. Association with ethnicity was not tested in Armenia due to the small share of ethnic minorities in the country.

What reasons do people give for their views?

The survey also investigated the reasons for people’s opinions. In both Georgia and Armenia, the overwhelming majority of those who felt that the dissolution of the Soviet Union had had a positive impact gave their country gaining independence as the main reason. Of those who felt it had been bad for their country, people’s economic situation having worsened was the most common response.

However, amongst those who felt that the dissolution of the Soviet Union had had a negative impact, different demographic groups prioritised different reasons.

Older people in Georgia and Armenia were more likely to resent that travel within the former USSR had become more difficult.

People with a secondary education or below perceive the lack of free healthcare and education as a greater loss than people with higher education do.

In Armenia, the country’s economic situation having worsened was of greater concern to people without a higher education.

Older people and people in rural areas saw damaged ties with friends and relatives as a larger problem than younger people and residents of the capital. People in rural areas in Armenia were also more likely to attribute their negative assessment to a decline in the availability of jobs.

Overall, Georgians felt more positive than Armenians about the impact of the collapse of the Soviet Union on their country, but the reasons that people gave for their assessments were similar in both countries.

Note: The analyses of different groups’ views in the above uses binary logistic regression, where the dependent variable is either a) thinking the dissolution of the USSR is a good or bad thing, or b) the reason why the dissolution of the Soviet Union was a bad thing. The independent variables included gender, age group, ethnicity, settlement type, level of education, wealth, and employment status.