A year before Georgia’s general elections, a CRRC survey found that less than half of surveyed Georgian partisans would remain loyal to their favoured party if its leader were to establish a new party, with supporters of the ruling party more likely to stick with their party than supporters of the opposition.

In recent years, political experts and analysts have argued that parties in Georgia function more on the basis of their political leaders’ popularity, rather than as genuine political organisations.

This would suggest that if political leaders left their party and established a new one, a substantial portion of their voters would go with them.

To test this hypothesis, CRRC Georgia conducted a public opinion poll in October 2023, a year before Georgia’s next general elections.

The data suggests that only four out of ten partisans would stay with their party if its leader left. However, supporters of the ruling Georgian Dream party are more likely to stay with their party, while opposition supporters more likely to be unsure or follow their party’s leader.

Respondents were asked to identify the political party with which they identified most closely.

Those respondents who named a political party (35% of respondents to the survey) were then asked to imagine a scenario in which a leader of their favoured party decided to cut ties with the party and establish a new party. Respondents were then asked to report how they would vote—would they still vote for their favoured party, or for the one that had been newly established?

| Leader | Party |

| Bidzina Ivanishvili | Georgian Dream |

| Mikheil Saakashvili | United National Movement |

| Giorgi Gakharia | For Georgia |

| Zurab Girchi Japaridze | Girchi More Freedom |

| Mamuka Khazaradze | Lelo |

| Irma Inashvili | Alliance of Patriots |

| Shalva Natelashvili | Labour Party |

| Zurab Makharadze | Conservative Movement - Alt Info |

| Giorgi Vashadze | Strategy Aghmashenebeli |

| Giga Bokeria | European Georgia |

| Aleko Elisashvili | Citizens |

| Elene Khoshtaria | Droa |

| Iago Khvichia | Girchi |

| Anna Dolidze | For the People |

| Nino Burjanadze | Democratic Movement |

| Zviad Dzidziguri | Conservative Party |

| Fridon Injia | European Socialists |

| Levan Vasadze | ERI |

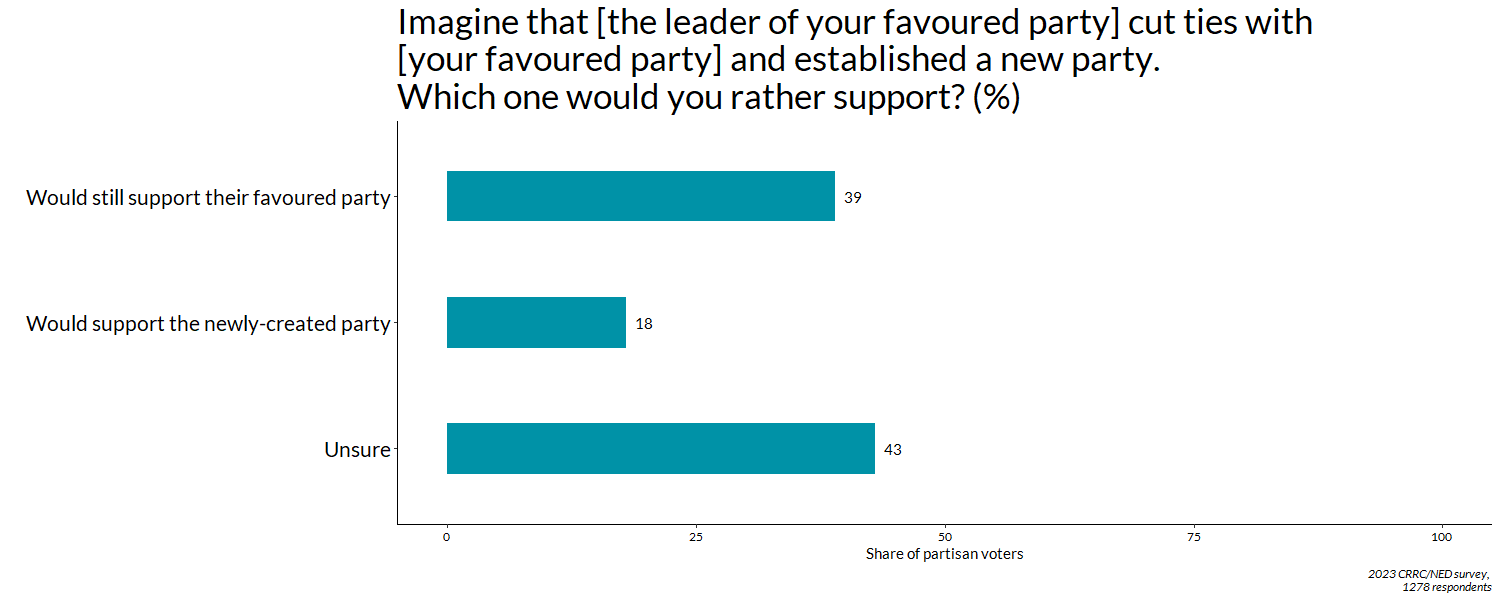

Four out of ten partisans (39%) said they would still vote for their favoured party. Approximately every fifth partisan voter (18%) said they would change their partisan preference and would vote for the new party. A plurality of partisans (43%) said they did not know which party they would vote for or refused to answer.

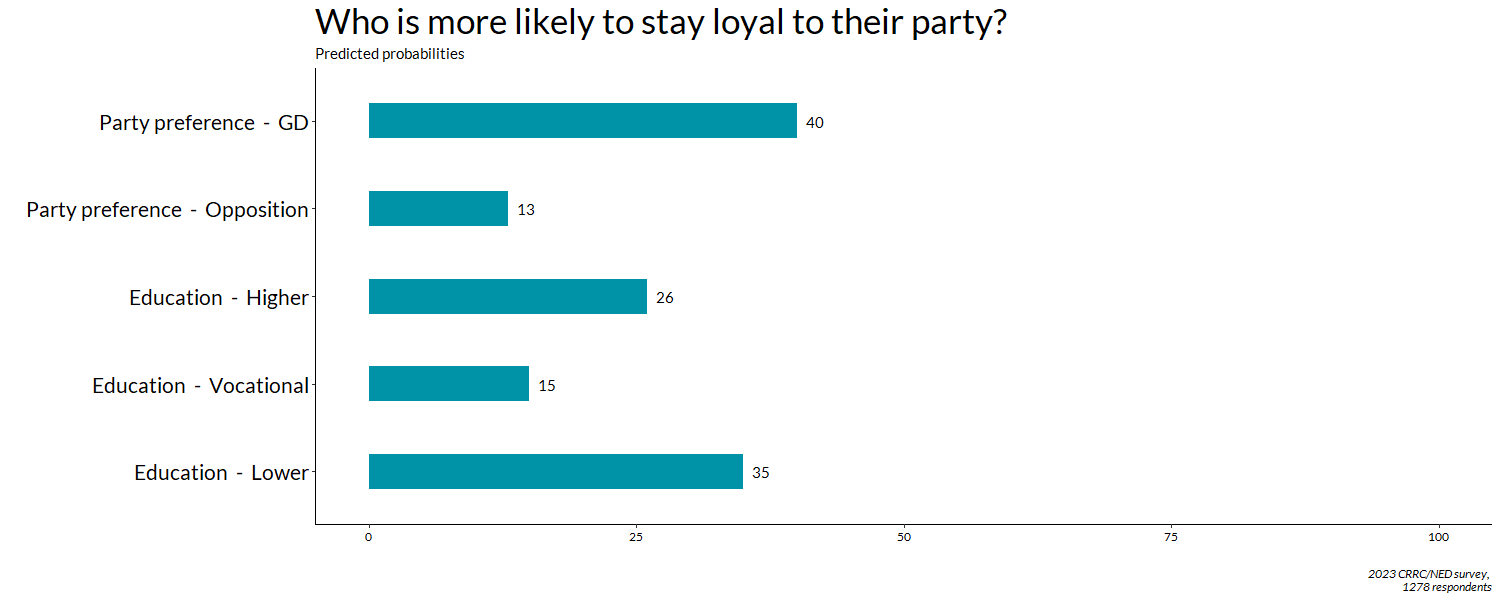

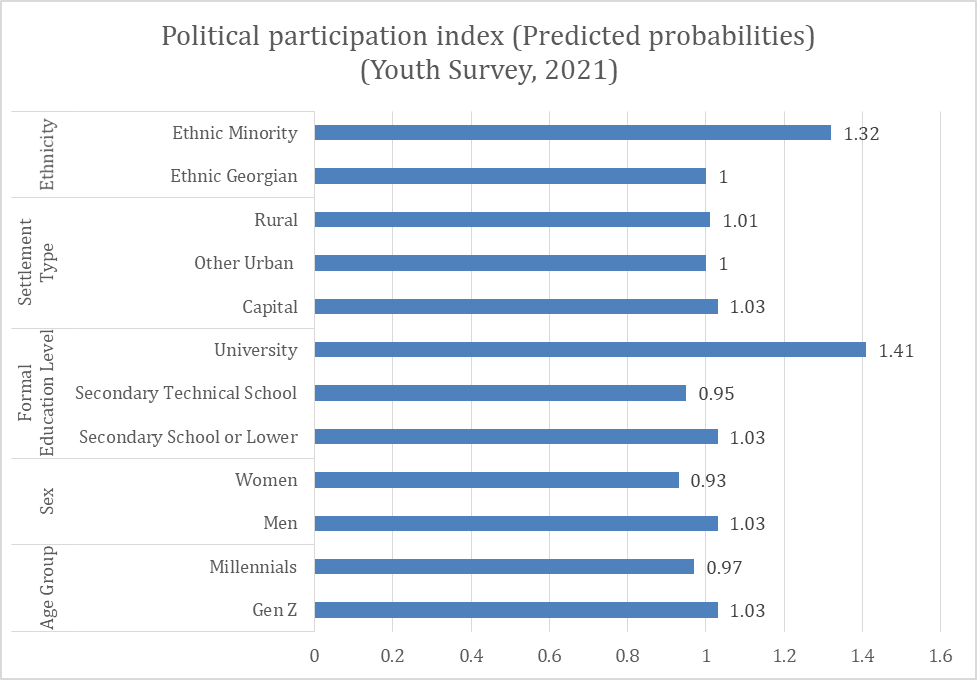

Further statistical analysis shows that some groups are more likely to stick with their favoured party even when its leader launches a new political venture. People with vocational education are less likely to stick with their favoured party than people who have a lower or higher level of formal education.

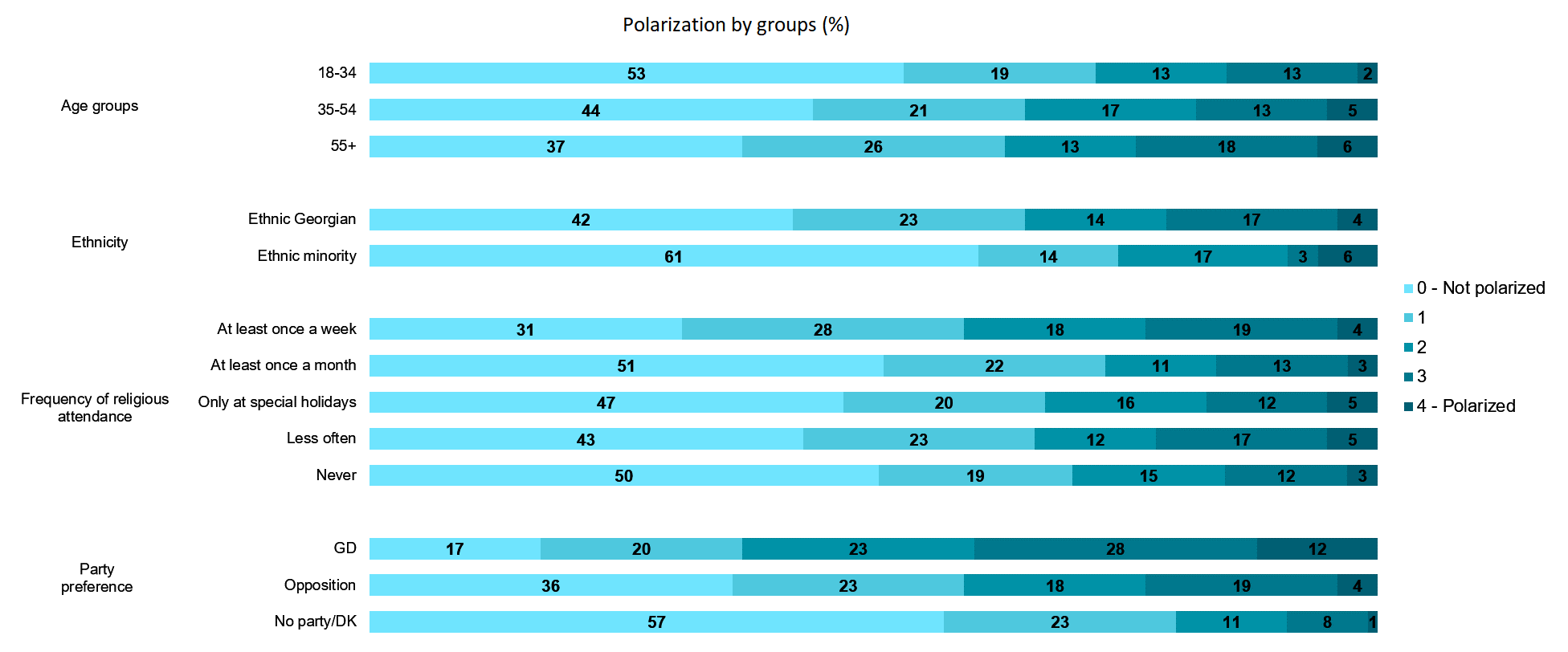

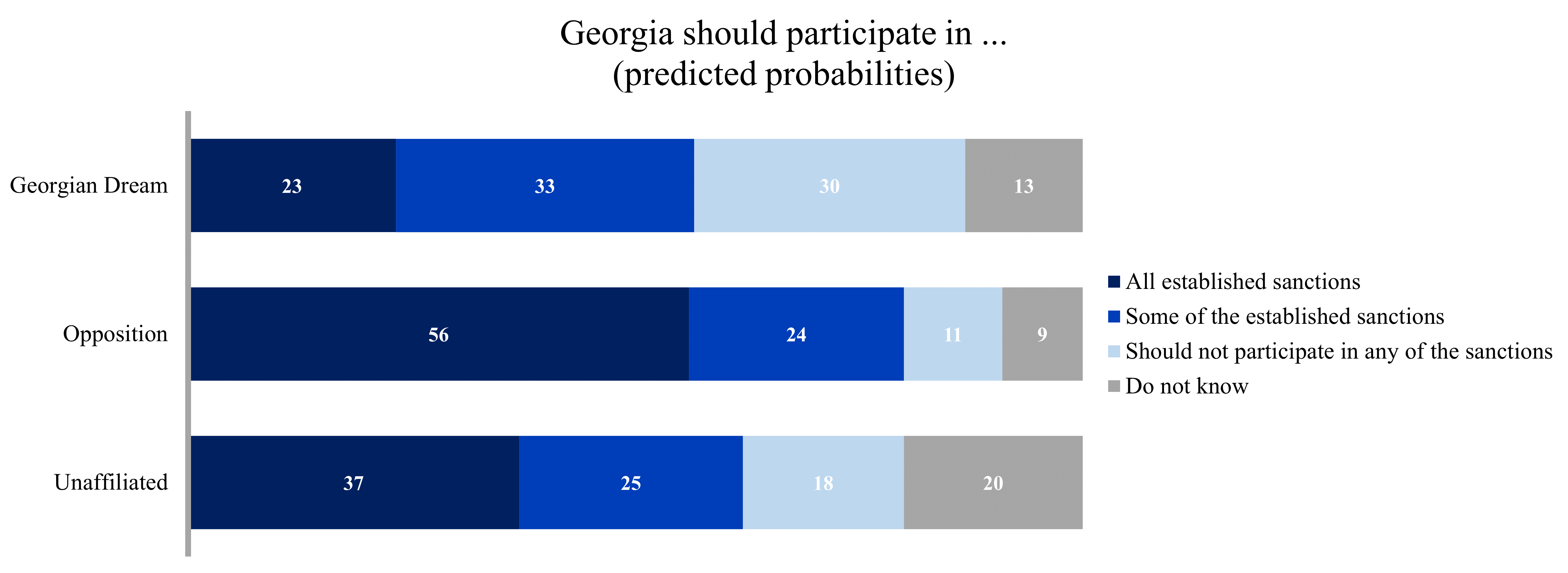

Party affiliation is also associated with whether or not voters are willing to stick with their current preferred party. Supporters of the ruling party are 27 percentage points more likely to say they would still vote for Georgian Dream if the party’s founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili, established a new party than opposition supporters when asked the same question regarding their parties’ leaders.

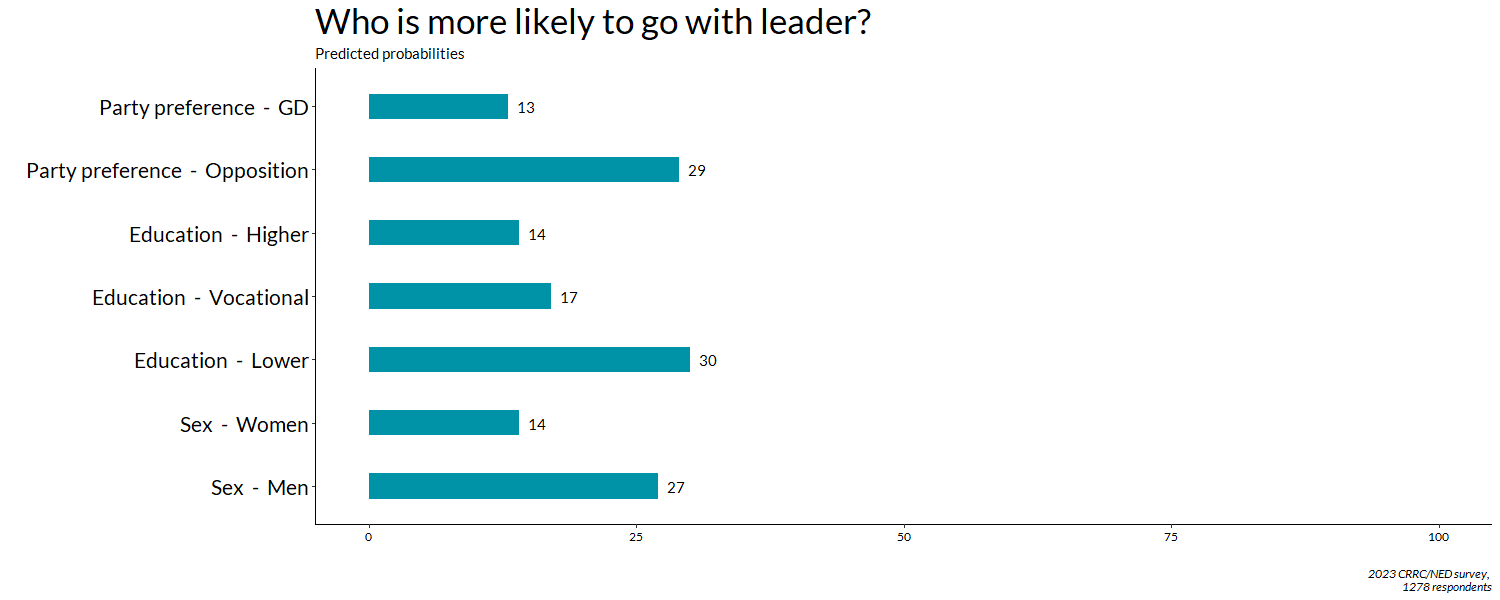

Regarding whether voters are willing to follow their party’s leaders, similar trends emerge.

Opposition supporters were 16 percentage points more likely to report they would vote for a party newly founded by their party’s leaders than Georgian Dream supporters.

People with lower levels of formal education were more likely to follow their party’s leader than people with higher levels of formal education.

Men were also more likely to follow a leader to a new party than women.

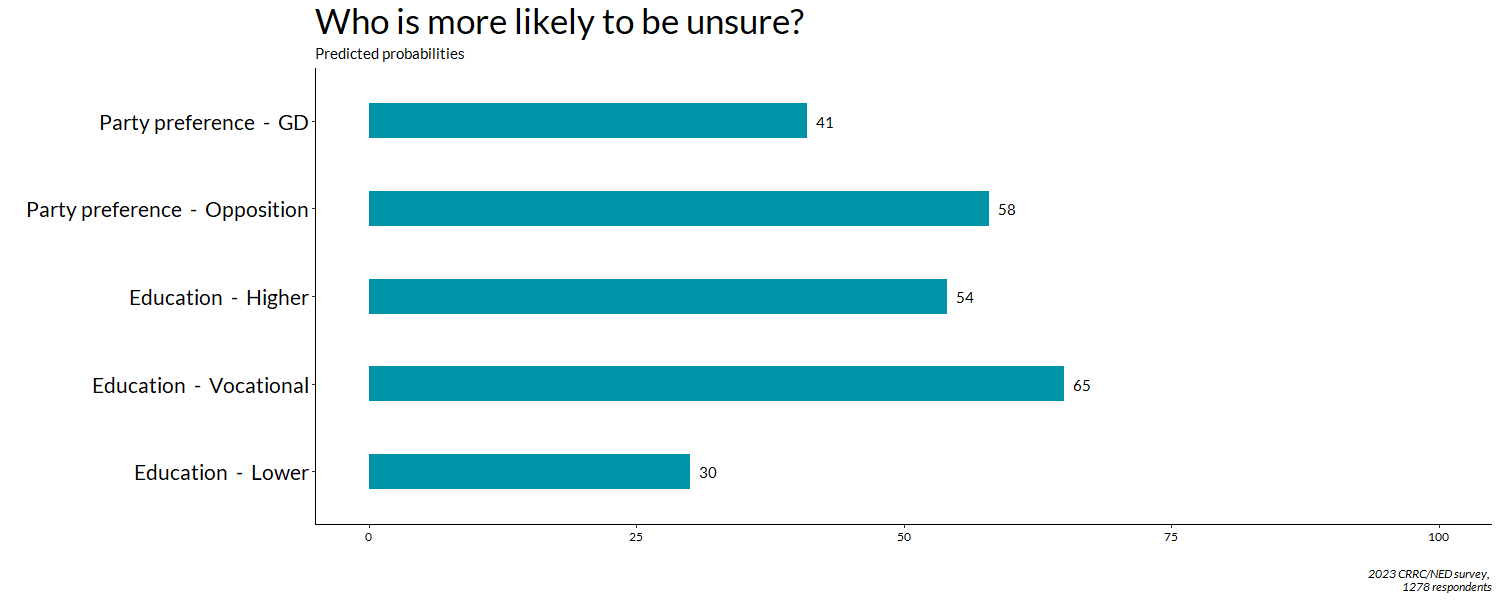

However, opposition supporters were also 17 percentage points more likely to be unsure of how they would vote if the leader of their favoured party established a new party compared with ruling party supporters.

People with higher education and vocational education are more likely to be unsure than people with lower levels of formal education.

The above data supports the idea that Georgian political parties are at least partially driven by their leaders, with only four out of ten partisans reporting they would stick with their favoured party if its leader launched a new political venture. Moreover, one in eight ruling party supporters and one in three opposition supporters reported they would follow their leader to a new party.

However, multiple other possible explanations for the data likely explain the differences between ruling party and opposition supporters.

First, the line between the ruling party and the state is often blurred, meaning that Georgian Dream’s supporters might continue to support the party on the basis of it remaining in power. Second, at the time of the survey, Bidzina Ivanishvili had formally distanced himself from politics. As a result, some Georgian Dream supporters might have supported other leaders within the party and the party’s policies, rather than its founder. Finally, many of the opposition parties which the public reported supporting were founded by former members of the UNM who left or are otherwise dominated by a single personality. In turn, many of their voters are likely already voting for the party based on its leader.

Despite the above, ties appear to be stronger to the party itself for Georgian Dream supporters than for opposition supporters.

Note: The above data analysis is based on logistic regression models, which included the following variables: age group (18-34, 35-54, 55+), sex (male or female), education (completed secondary/lower, vocational, higher), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), employment status (not working, working in the private sector, working in the public sector), religious attendance (regularly, on special occasions, rarely or never), and party identification (Georgian Dream, Opposition).