This week's blog post was originally published on Friday, August 29th on New Eastern Europe. The original version may be viewed here.

Review of Bittersweet Europe. Albanian and Georgian Discourses on Europe, 1878-2008. By: Adrian Brisku. Publisher: Berghahn Books, August 2013.

Since independence, Georgia has been on what has often looked like a quixotic quest towards joining the EU. Multiple wars, a resurgent Russia, breakaway territories and a consistently difficult economic situation which has gone through hyper-inflation and has had consistently high unemployment and underemployment over the last 25 years must, at the minimum, make prospects for EU integration seem distant at best to many in Brussels. Yet, with the recent

signing of the Association Agreement with the European Union on June 27th 2014, Georgia is closer to its European dreams than ever. Remembering that the

EuroMaiden protests, which were the match to the powder keg igniting the Ukraine Crisis, were set off by former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych’s

failure to sign an association agreement that would have brought Ukraine closer to Europe and considering the historical ambivalence among elites in Albania and Georgia towards Europe over the course of the last 130 years, there could not be a more important time for academics, policymakers and journalists working on the Eurasian region to read Adrian Brisku’s

Bittersweet Europe.

Brisku skillfully disentangles the often competing webs of discourse on Europe coming out of Georgia over the past 130 years. The book simultaneously decentres Caucasus watchers’ purview through placing Georgian discourse on Europe in a comparative perspective with Albania’s conversations on Europe over the same period. Furthermore, by implanting the conversation in broader pan-European historical frames, the author provides valuable insight into how Georgia’s relationship to Europe has been conditioned historically.

Since the Russian imperial period, discourse on Europe has been mixed, but one of the most important points of contention in Georgia has been whether the country would “look West” on its own or look north to Russia in order to look West to what Brisku describes as the “triadic Europe.” The triadic Europe which Brisku refers to is Europe “as geopolitically important; as a torchbearer of progress; and as the symbol of civilisation and high culture”. This distinction is valuable in that it lends an understanding to the often confounding claims of Europeanness from Georgian elites due to its ambiguous geographical location on the crossroads of Europe and Asia and the sometimes questionable reasoning behind such claims by providing the polysemous meaning of Europe in Georgia.

In diametric contrast to nationalist leaders today, the Georgian “Father of the Nation” and canonized Saint in the Georgian Orthodox Church, Ilia Chavchavadze, believed that Georgia should and would move towards Europe, but through its relationship with Russia, as Georgia was a part of the Tsarist Empire at the time. In opposition to this, Noe Zhordania, another aristocrat but one who had studied in France during his first term in exile from Georgia, developing an inclination towards French Socialism in the process, and the eventual first and only president of the independent, Menshevik, Georgian Republic of 1918-1921, thought that Georgia’s relationship to Europe should not be mediated through the Russian space. The contentions surrounding Europe and Georgia as a part of Europe would not end here though.

With the First World War and the Bolshevik takeover of Georgia, the discourse shifted. As the socialist state was supposed to be the vanguard of progressivism in the world, Georgia, as part of the Soviet Union, was meant to be in a position to help the working classes of Europe towards the progress represented by socialism. Much like how Karl Marx had flipped Georg W.F. Hegel on his head in philosophy, who and what represented progress had been spun around in the Georgian discourse.

Georgia has had a pro-European policy since independence, with short exceptions, and Brisku traces this shift back to the 1975 signing of the Helsinki Accords. In Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, through co-founding the Georgian Helsinki Group, began the discursive shift towards relations with Europe directly instead of through the mediation of the Soviet state. In doing so, he set the stage for changes to come. From this point onward, with one exception, and especially after independence, a pro-European discourse emanated from Georgia.

In a strange twist of irony, the exception to Georgia’s pro-EU discourse came from the same person who re-ignited it, Zviad Gamsakhurdia. This though, was not the dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia which founded the Helsinki Group in Tbilisi nor the man who led the anti-Soviet movement in Georgia to the Soviet Union’s collapse, but the Zviad Gamsakhurdia who was elected the first head of state of Georgia after independence. His rule was characterised by strong nationalist tendencies which alienated the country’s ethnic minorities leading to the de facto loss of control of South Ossetia for Georgia. From human rights advocate and dissident to human rights violator, Zviad Gamsakhurdia in his turn moved away from Europe due to European criticism of his human rights abuses.

The persistent question which has dominated and lay beneath the surface of the discourses on Europe in both Georgia and Albania is “Are we European?” From this underlying question, Brisku highlights the ethnocentric euro-centrism that emerged in both contexts from anxieties and insecurities and the overcompensation resulting from this question. In both contexts, prominent thinkers and politicians ended up emphasising the countries’ ancient histories and numerous invasions in order to justify their Europeanness in contrast to cultural and confessional differences compared to predominant conceptions of what it conventionally meant to be European. Mikheil Saakashvili, Georgia’s third post-Soviet elected head of state

stated in European Parliament that"since the time when Prometheus was chained to our mountains and the Argonauts came to our country in search of the Golden Fleece ... we are an ancient European nation." Hyperbole not intended.

Further contributing to these anxieties and adding to the reader’s understanding of how they emerged, the book tracks how European powers have interacted with the two countries historically. Being small countries, the feeling that interaction, and more importantly the frequent lack thereof, was based on Europe’s interests have contributed to anxieties in both nations.

The book concludes that the political and intellectual elite in Georgia and Albania have historically been “ambivalent” about their relationship to Europe. Today, in Georgia, we can see this ambivalence quite strongly. When it comes to policy, Georgian support for closer ties to the EU is unquestionable. The ruling Georgian Dream Coalition and the opposition United National Movement disagree on what seems to be just about everything, but the one thing that neither side has wavered from is their dedication to further Euro-Atlantic integration. Moreover, according to the study, “

Knowledge and Attitudes towards the EU in Georgia: Changes and Trends 2009 – 2013” conducted by

CRRC-Georgia for the

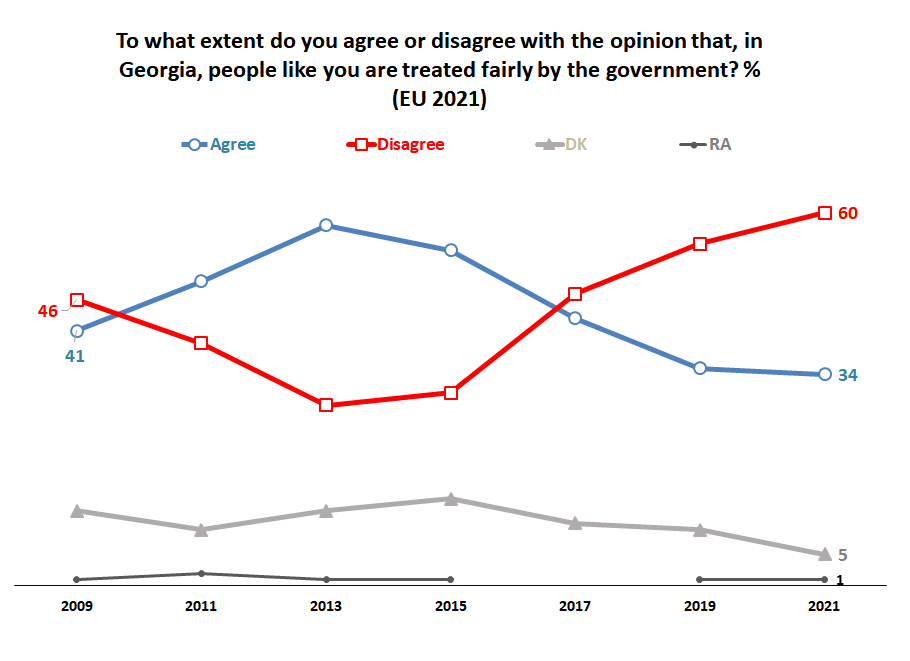

Eurasia Partnership Foundation in 2013, 83 per cent of Georgians reported that they would vote to join the EU tomorrow if a referendum were to be held, with support consistently near these levels in recent years. At the popular and elite level, support for closer integration with Europe is clear.

Despite this clear policy direction, opposition to the recently passed

anti-discrimination law, which was required for the signing of the Association Agreement with the EU, highlights that many Georgians still oppose or potentially misunderstand some features commonly associated with Europe, specifically the defence of sexual minority rights. Controversy surrounded the bill as a number of priests claimed that the bill would lead to the legalisation of gay marriage in Georgia (it wouldn’t and hasn’t), something the population of the country would largely be against. Moreover, the passing of the law at certain times was opposed by the Patriarch Illia II of the Georgian Orthodox Church, who is widely considered to be the

most trusted person in Georgia. In this way, aspects of the cultural Europe, which Brisku identifies early on, are those which many Georgians today are still ambivalent about.

Overall,

Bittersweet Europe offers a masterful juxtaposition of Georgian and Albanian discourses towards Europe in addition to the accompanying insecurities over Europe and Europeanness in both countries. This in conjunction to the decentring effect gained through the added context leads the reader to a better understanding of Georgia’s history and relationship to Europe - something needed now more than ever.