Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. This article was written by Katharine Khamhaengwong, an International Fellow at CRRC Georgia, and Makhare Atchaidze, a researcher at CRRC Georgia. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, the Europe Foundation, or any related entity.

Data CRRC has collected shows that there have been significant changes in the attitudes of Georgians towards women’s sexual freedoms since 2013, especially among Muslims, who have seen a large decrease in rates of disapproval, although this has not translated to a significant increase in approval.

The data was collected as part of the Knowledge of and Attitudes towards the European Union in Georgia survey, carried out for the Europe Foundation between 2013 and 2023.

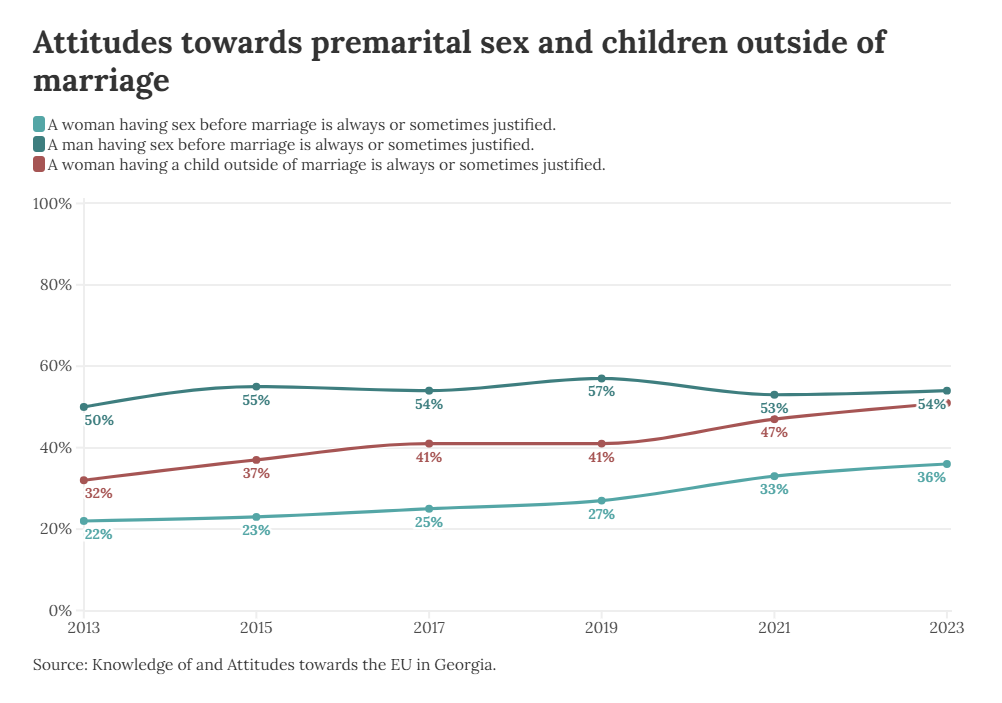

According to the resulting statistics, the share of Georgians reporting it is always or sometimes justified for a woman to have premarital sex increased from 22% in 2013 to 36% in 2023. Similarly, in 2013, only 32% of Georgians said it was always or sometimes justified for a woman to have a baby outside of marriage, compared with 51% in 2023. These numbers show that attitudes towards sex are loosening, particularly with regard to women. But whose attitudes are changing?

These numbers show that attitudes towards sex are loosening, particularly with regard to women. But whose attitudes are changing?

In 2013, 87% of Muslims said that it was never justified for a woman to have sex before marriage, compared to 67% of Armenian Apostolic Christians and 66% of Orthodox Christians. Ten years later, only 58% of Muslims said it was never justified, compared to 68% of Armenian Apostolic Christians and 50% of Orthodox Christians.

However, while the number of Muslims saying that pre-marital sex was never justified fell dramatically, this was not accompanied by a proportionate increase in Muslims saying pre-marital sex was justified. Indeed, there was only an increase from 6% of Muslims reporting that pre-marital sex was sometimes or always justified in 2013 to 15% in 2023. During this same period, the number of Muslims who refused to answer the question went up from only 1% in 2013 to 18% in 2023.

In contrast, the decrease in opposition to pre-marital sex by Orthodox Christians came with a notable increase in the percentage that believed pre-marital sex was always justified — in 2013, only 3% of Orthodox Christians agreed that pre-marital sex was always justified, compared to 13% in 2023. The numbers for pre-marital sex being sometimes justified also went up, from 21% to 26%. The answer refusal rate for this group did not change significantly. This pattern is repeated with attitudes toward having children outside of marriage.

This pattern is repeated with attitudes toward having children outside of marriage.

In 2013, 84% of Muslims said this was never justified, while in 2023 only 55% reported the same. In this case, the number of Muslims who said a child outside of marriage was always justified did move from 0% in 2013 to 5% ten years later, but again the biggest change was in those who refused to answer, going from 2% in 2013 to 16% in 2023. The percentage of Muslims who said pre-marital sex was never acceptable decreased by 29 points, as did the percentage of those who said children outside of marriage was never acceptable. The numbers for Orthodox Christians were similarly consistent, both declining by 16 points.

The percentage of Muslims who said pre-marital sex was never acceptable decreased by 29 points, as did the percentage of those who said children outside of marriage was never acceptable. The numbers for Orthodox Christians were similarly consistent, both declining by 16 points.

The Armenian Apostolic community differed, however — while their views of pre-marital sex for women were quite consistent, the percent who said having a child outside of marriage was always unjustified went from 80% in 2013 to 60% in 2023. Unlike the case with changing Muslim views, this decrease largely came from Armenian Apostolic Christians saying that children outside of marriage were sometimes (17% to 30%) or always (0% to 5%) justified. The share of refusals did not change significantly.

Meanwhile, Orthodox Christians showed the biggest changes in full approval of pre-marital sex, as well as full approval of having children out of wedlock.

Opposition to women having children outside of marriage and to women having premarital sex decreased in Georgia from 2013 to 2023.

Opposition to women having children outside of marriage and to women having premarital sex decreased in Georgia from 2013 to 2023.

Some of the biggest decreases came from Georgian Muslims, who are among the religious groups most disapproving of these behaviours. However, this decrease in opposition does not coincide with an increase solely in approval — instead, in addition to a degree of greater acceptance, Muslims increasingly refused to answer questions about sex.

The data used in this article is available here.