Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Tinatin Bandzeladze, a senior Researcher at CRRC-Georgia and Mariam Kobaladze, a senior Researcher at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC-Georgia, Caucasian House, or any related entity.

A CRRC survey found that trust in Georgia’s Interior Ministry and the police is closely tied to perception of the ministry’s political independence, or lack thereof.

In summer 2022, CRRC Georgia and the Social Justice Center partnered on a nationwide public opinion survey on state and personal security. It found that while the Interior Ministry was one of the most trusted institutions in the country, many respondents were concerned that the ministry lacks transparency and political impartiality.

Georgia’s Interior Ministry is largely made up of and closely associated with the country’s police, with police officers often seen as representatives of the ministry. Previous research has demonstrated that police need public trust to effectively carry out their mandate to fight crime and maintain public safety.

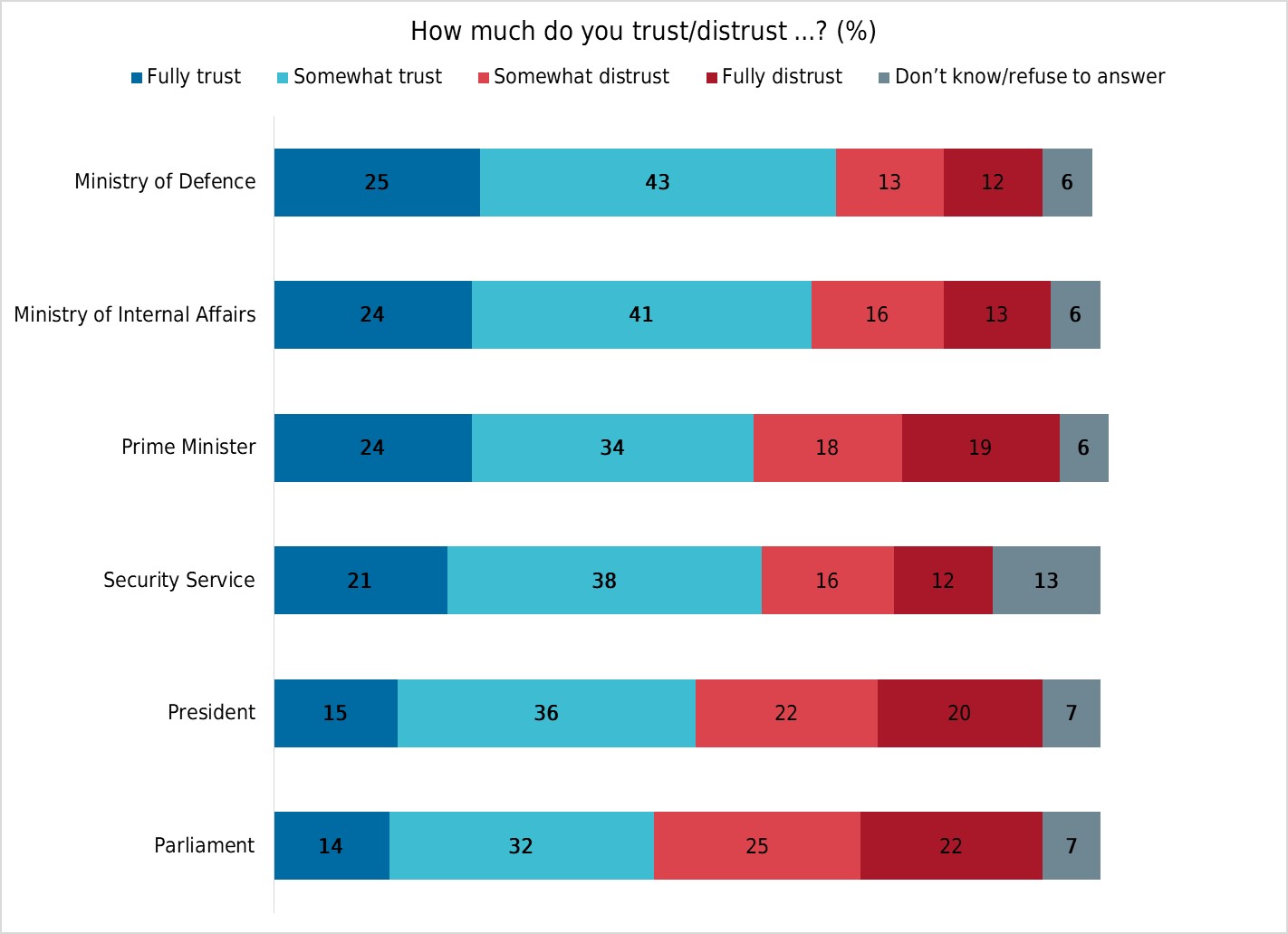

According to the 2022 survey, a majority of the Georgian public trust the Interior Ministry. About two thirds (65%) of the public has full or partial trust in the ministry. This is lower than that of the Defence Ministry (68%), but outperforms the Prime Minister (58%), the State Security Service (59%), the President (51%), and the Parliament (46%).

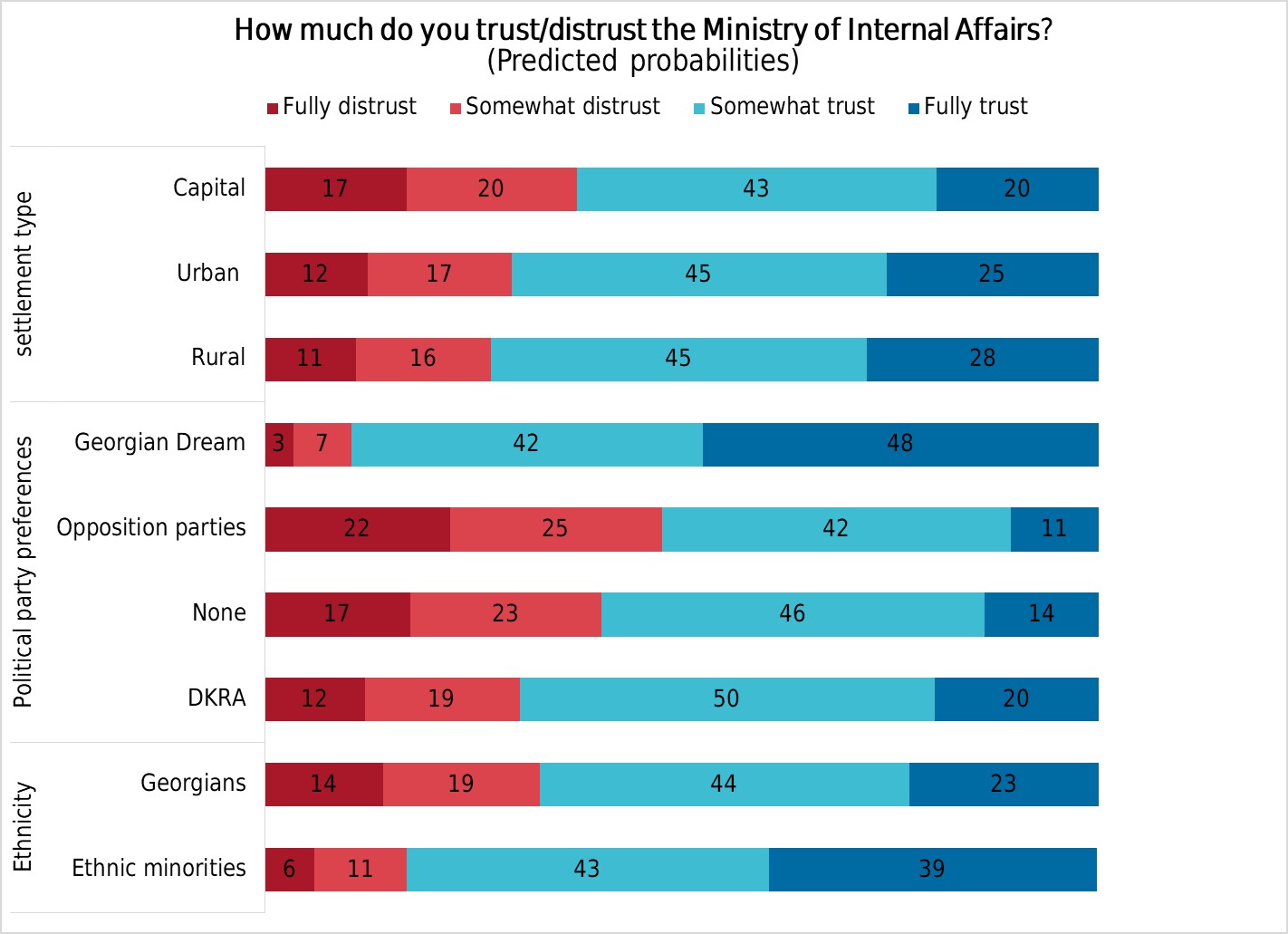

Trust in the Interior Ministry varies with a number of social and demographic characteristics.

Residents of Tbilisi are less likely to fully trust the Interior Ministry than residents of other cities and people in rural areas.

Trust in the ministry is also associated with party preferences. People who support the ruling Georgian Dream party are more inclined to fully trust the ministry than supporters of opposition parties and those who support no party. Almost half of ruling party supporters fully trust the Interior Ministry.

Ethnic minorities fully trust the Interior Ministry at nearly twice the rate of ethnic Georgians.

Other demographic characteristics do not predict trust in the ministry.

Research by others suggests that trust in the police is connected more to perceptions of police fairness than with perceptions of police effectiveness in dealing with crime.

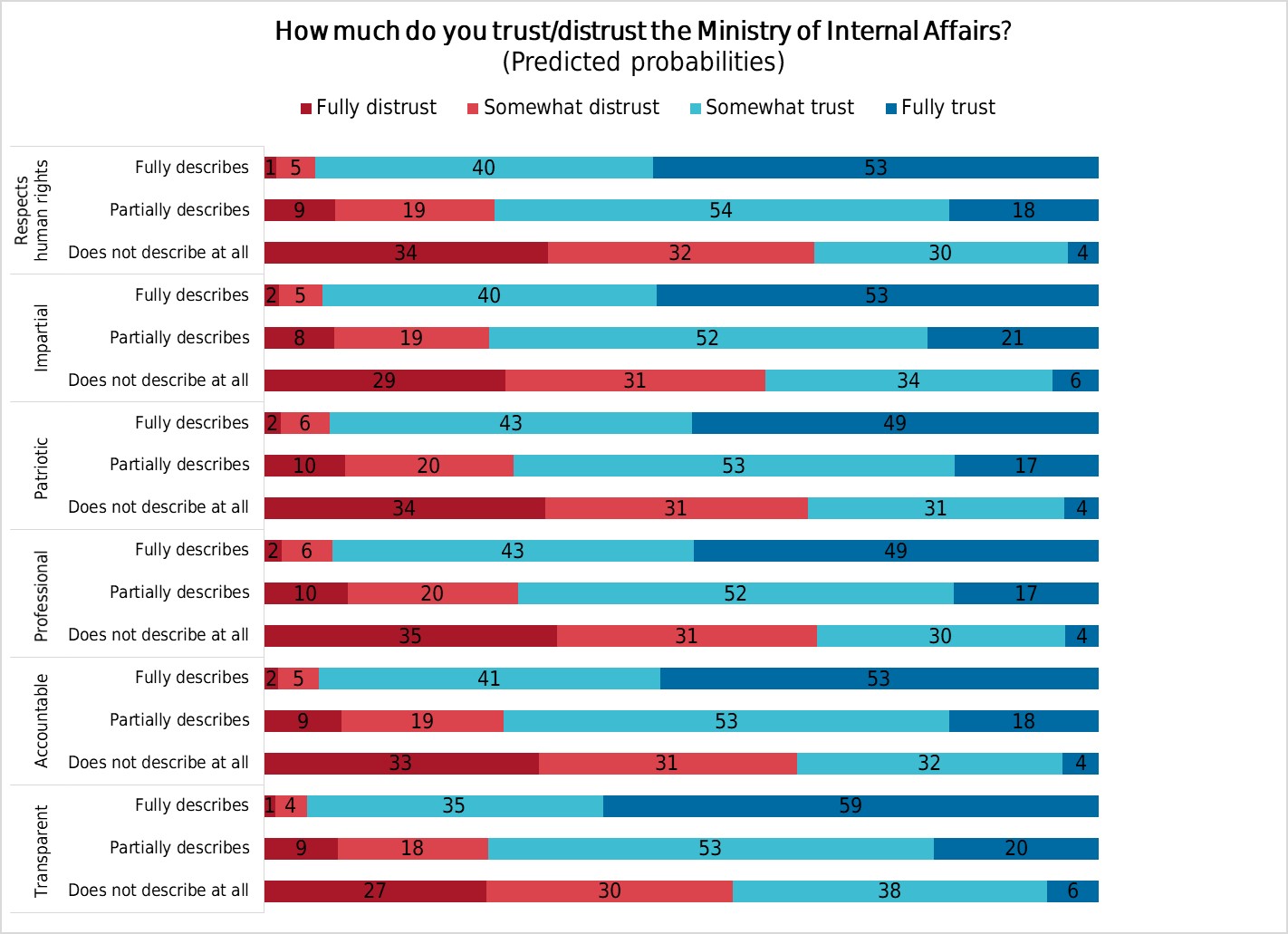

In relation to that, the study also asked about whether the public perceived the Interior Ministry as patriotic, professional, impartial, and transparent. The surveyed respondents viewed the ministry as patriotic (23%) and professional (23%) more frequently than they perceived it to be impartial (15%) and transparent (14%).

The above opinions are associated with trust in the Interior Ministry. Those that think these characteristics fully describe the ministry, also nearly unanimously trust it. In contrast, majorities of those that do not think each characteristic describes the ministry also mistrust it.

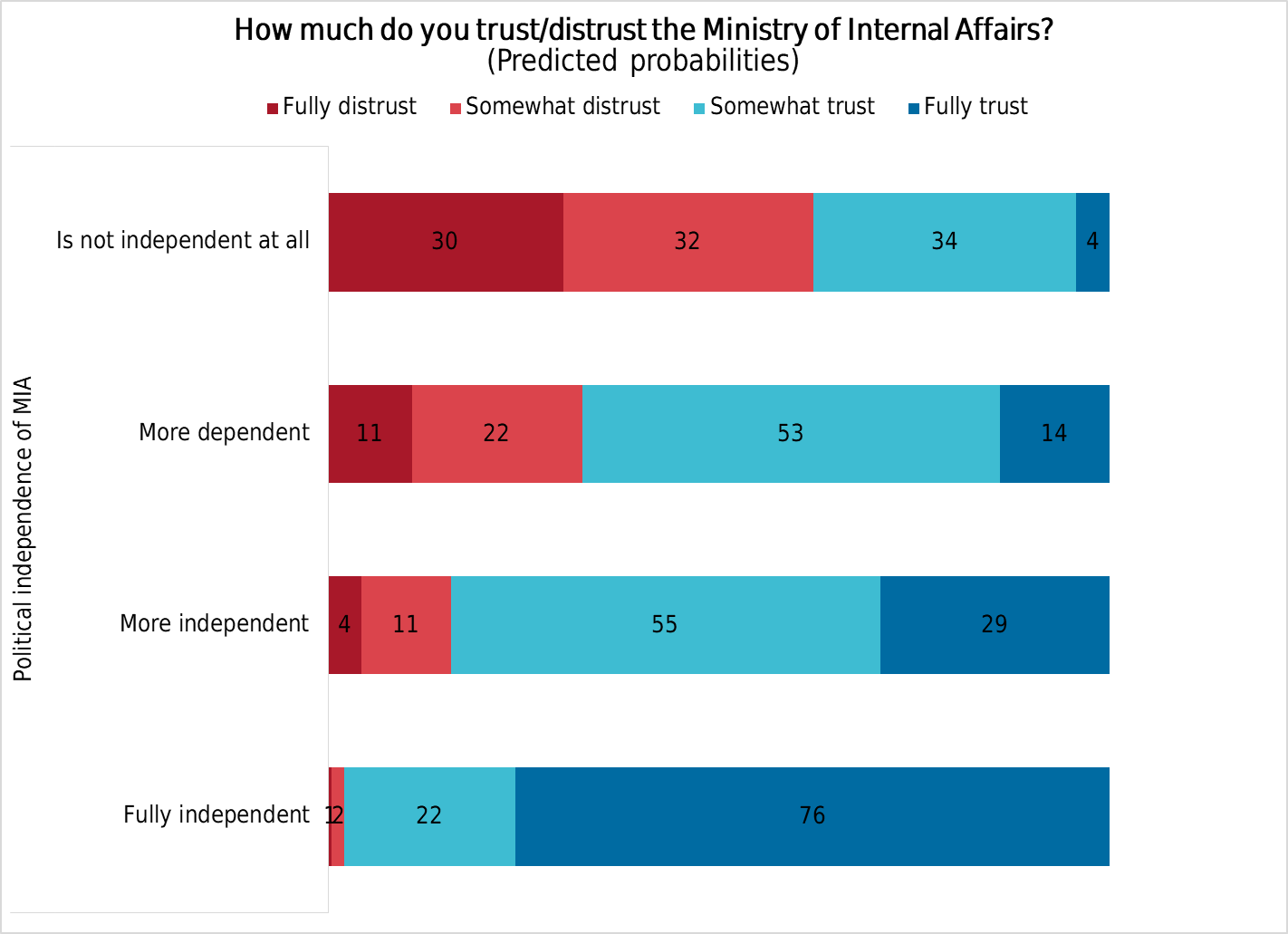

Respondents were also asked if they believed the Interior Ministry was independent from politics. Only 9% of those surveyed felt that the Interior Ministry was fully independent from political influence, while 23% believed it was more independent than dependent. On the other hand, 47% reported believing that the ministry had no political independence or it was more politically ‘dependent’ than independent. The remaining 21% did not know or refused to answer the question.

The data indicate that opinions regarding political independence strongly predicted trust in the ministry. While there was a 62% chance an individual would fully or partially distrust the Interior Ministry if they believed it was not independent at all, the likelihood dropped to 2% among those who believed it was fully independent.

While a majority of Georgians reported trusting the Interior Ministry, and thereby the police, in 2022, relatively few reported they were transparent and impartial, with only a third of respondents viewing them as politically independent. A belief that the ministry lacks independence as well as a lack of belief that it is transparent, accountable, professional, patriotic, impartial, and respects human rights are strong predictors of whether people trust the institution.

Note: This blog makes use of ordinal logistic regression analysis. The dependent variable was trust in the MIA, with don’t know and refuse to answer responses removed. The independent variables included: sex, age, employment status, level of education, a wealth index, settlement type, political sympathy and ethnic identity.