- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of social dialogue capacities at both a sectoral and company level in each country;

- Identify needs for further research to assess the impact of social dialogue on the overall economic development of the country and the region.

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

Social Dialogue in the Eastern Partnership Countries

Posted by

Arpine

at

4:59 PM

3

comments

![]()

Friday, February 12, 2010

Social networks in rural and urban Georgia

It is often stated that life in a city is fundamentally different from that in rural areas. In the West, village life is said to be more intimate, and its inhabitants more caring about their peers, with strong ties between neighbors and family members. Can this also be said in the South Caucasus? After all, family relations and friendships are supposed to be strong in countries like Georgia. Do these ties reach into the cities, erasing the difference between strong social networks in rural areas and the more anonymous, independent urban setting?

The data from our 2008 Data Initiative (DI) gives us several clues as to how to answer this question. Georgian respondents in three settlements types - rural, urban (excluding the capital), and Tbilisi - were asked about their views on their social environment. The results showed that people with positive feelings about their social networks were, contrary to our expectations, most likely to be found in the capital, but least likely in other urban areas.

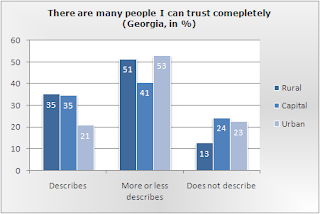

According to our data, inhabitants of rural settlements and Tbilisi are most likely to have enough people to trust. Villagers also have the lowest percentage of people lacking this kind of social support. Our question asked the respondents whether they had “many people to trust completely.” Respondents were most likely to agree with this statement in rural areas and Tbilisi (both 35 percent). Urban Georgia came out last, where only 21 percent felt they had trustworthy people around. By contrast, 24 percent in Tbilisi and about 23 percent in other urban areas said they cannot trust many people in their social environment. In rural Georgia only 13 percent of respondents said the same. The neutral answer reading “the statement more or less describes my feelings” was most often recorded in urban areas (53 percent), followed by rural Georgia (51 percent) and Tbilisi (41 percent).

When asked about people close to them, respondents in Tbilisi were more often satisfied with their situation than those living in other settlement types. Inhabitants of rural areas were least likely to express a lack of close friends. In response to the proposed statement “I have enough people I feel close to”, urban Georgia had again the least favorable response pattern. In cities like Batumi or Rustavi, only 41 percent of respondents stated that they have many close people around. Fifty percent in the capital and 45 percent in rural areas agreed with this statement. This time, Tbilisi also had the highest percentage of negative answers, with as much as 13 percent of the respondents thinking that they lack close friends. Only 9 percent of answers recorded in rural parts of the country, and only 10 percent in urban Georgia, reflected the same negative feelings. The neutral answer was most likely to be found in rural settings and urban areas (both 46 percent), followed by the capital (37 percent).

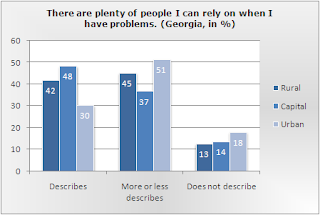

In response to the statement “there are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems”, once again more people in the capital than in other parts of Georgia agreed, and urban Georgia featured the highest percentage of respondents who miss reliable people when they encounter problems. In urban Georgia only 30 percent of the respondents felt safe to turn to their friends when in trouble, and there were 18 percent who thought that they cannot rely on their social environment in this way. Both in the capital and in rural areas, the spread between positive and negative answers is much higher: in Tbilisi a full 48 percent agreed that they have plenty of reliable people around, compared with 14 percent who disagreed. In rural areas 42 percent gave a positive and only 13 percent a negative answer. The percentage of respondents who chose “describes more or less my feelings” as their answer was lower in the capital (37 percent) than in rural (45 percent) and urban Georgia (51 percent).

Now, which settlement has the highest quality of social networks? If we take a negative definition (i.e. we search the type of settlement with the smallest percentage of respondents expressing a lack of sound social ties), rural life seems to be the best choice, with the fewest amount of people choosing the negative answers. If, however, we compare positive answers (i.e. we search the type of settlement where the highest percentage of respondents were satisfied with their social networks), the capital is ahead of rural settlements. With both definitions, urban Georgia (excluding the capital) comes out last in the comparison. This hints to the fact that city life might have significant drawbacks, but that they have been compensated in Tbilisi by factors not present in other urban settlements. By the way, people in the capital also tend to have a more pronounced opinion about these matters, with fewer respondents choosing the neutral answer in response to the three statements.

What are the factors that help Tbilisi to counterbalance some of the negative aspects of city life? Why does it have so many people satisfied with their social networks, without the large numbers of unsatisfied respondents found in other cities in Georgia? Some of these factors might be found with the help of our survey data. If you feel like exploring this interesting subject, or would like to see similar data for Armenia or Azerbaijan, we invite you to visit http://www.crrccenters.org/sda, where you can find all of our 2008 DI survey data for free, accessible via an easy-to-use web interface. Comments and ideas are appreciated.

Posted by

Malte

at

3:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Caucasus Barometer, Civil Society, Data, Data Initiative, Georgia, Perceptions, Sociology

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Top Ten Leisure Activities in Georgia

Find out what are the ten top leisure activities in Georgia, according to a nationwide survey recently conducted by CRRC.

Read the full article, which was recently published in Georgian Times, here.

Posted by

Nana

at

6:41 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Civil Society, Data, Georgia, Survey