Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Sasha Slobodov, an International Fellow at CRRC-Georgia, The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

In a recent CRRC survey on discrimination in Georgia, more Georgians agreed that a range of minority groups face challenges in the country than did three years prior, and they increasingly agree on the main issues that those groups face.

A survey on hate crime, hate speech, and discrimination in Georgia CRRC Georgia conducted for the Council of Europe in 2018 and 2021 found a number of changes in attitudes among the Georgian population toward the issues that minority groups face.

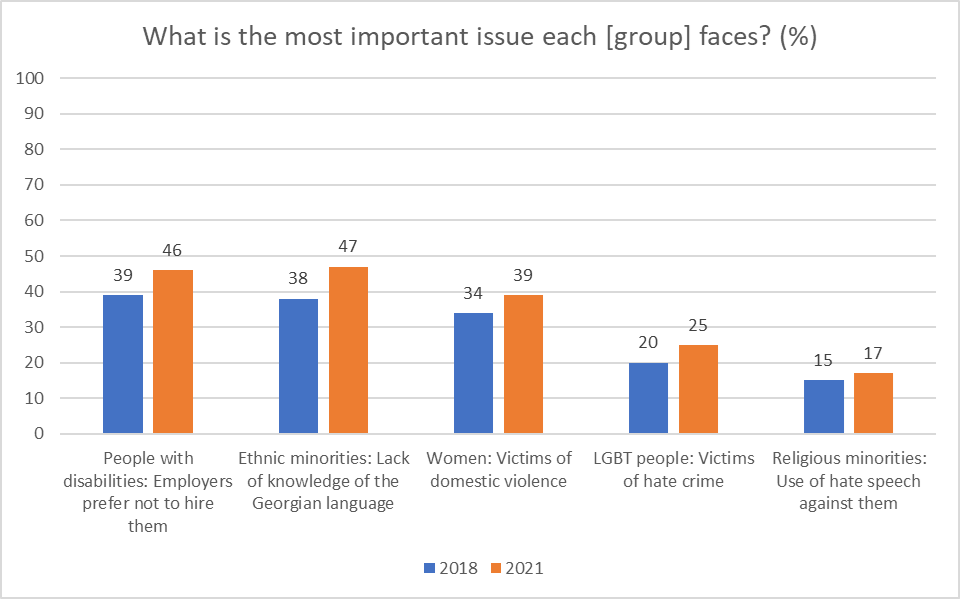

When asked what the biggest issue was that ethnic minorities faced in Georgia, the most frequently noted issue was lack of knowledge of the Georgian language in both 2018 (38%) and in 2021 (47%). For religious minorities, hate speech was believed to be the main issue they faced in both 2018 (15%) and 2021 (17%).

For women, in 2018, domestic violence was the issue (34%) most commonly cited, increasing to 39% in 2021. As for people with disabilities, a plurality of the public believed that employers preferring not to hire people with disabilities was the main issue they faced in 2018 (39%). This rose to 46% in 2021. Being a victim of hate crime was considered the largest issue for LGBT people (20%). This number increased to 25% in 2021.

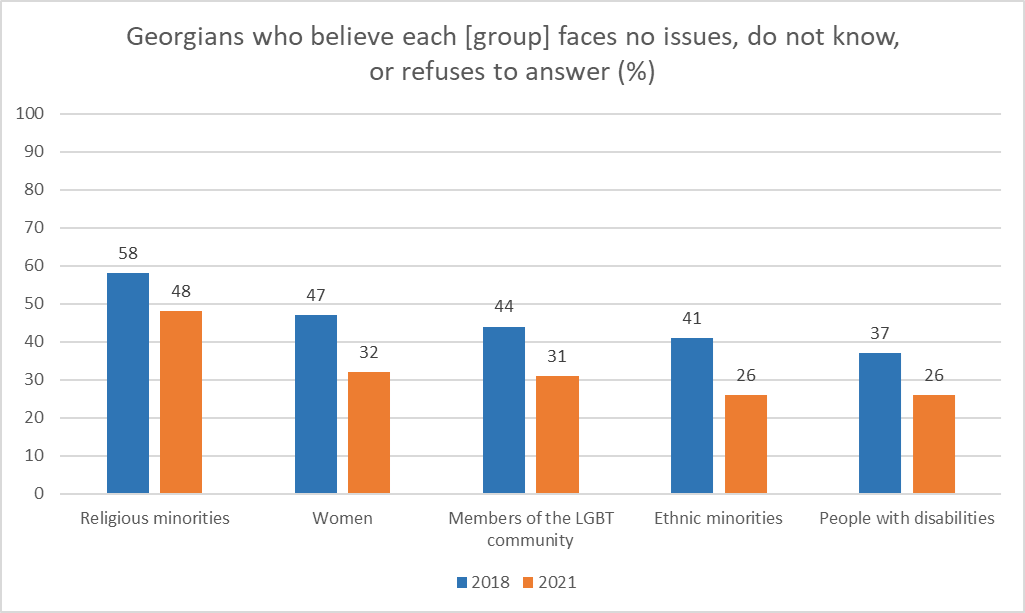

In both years, when asked what the main issues faced by each minority group were, respondents were also given the option to answer that the group faced no issues. Across all groups, the number of respondents who believed that the minority faced no issues decreased. Religious minorities were most often perceived to have no issues (38% in 2018, 27% in 2021), followed closely by women (34% in 2018, 17% in 2021), and then ethnic minorities (26% in 2018, 11% in 2021). The lowest percentage of respondents believed that people with disabilities (17% in 2018, 9% in 2021) and LGBT people (17% in 2018, 9% in 2021) faced no issues at all.

Many respondents reported that they did not know what the most important issue different minority groups faced was. People were least aware of the issues that LGBT people face (22% in 2018, 18% in 2021), followed closely by religious minorities (19% in 2018, 20% in 2021), and people with disabilities (19% in 2018, 16% in 2021). In both 2018 and 2021,14% reported that they did not know what the primary issue faced by ethnic minorities was. Few people also said they did not know what issues women face, at 12% in 2018 and 14% in 2021.

The above data suggests that Georgians increasingly agree on the biggest issues minority groups face, and that the share of people who believe that minority groups face no issues decreased between 2018 and 2021. Respondents were more likely to agree on the primary issues faced by people belonging to ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and women, meaning that majorities and minorities were likely to give increasingly similar responses. There was less consensus about the major issues LGBT people and religious minorities face.