Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. This article was written by Dustin Gilbreath, a Non-resident Senior Fellow at CRRC-Georgia and Givi Siligadze, a Researcher at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia, the National Endowment of Democracy, or any related entity.

A CRRC Georgia survey found that people living in Tbilisi were more willing to accept democracy-eroding policies if they believed that their preferred party was in power.

New data released in a CRRC-Georgia policy brief today suggests that a substantial portion of voters in Georgia’s capital tend to be hypocritical in their attitudes towards democracy-eroding policies, being more likely to support them if the party they prefer controls government. However, most do not support anti-democratic policies at all.

Following the first round of municipal elections in October 2021, CRRC-Georgia conducted a representative survey of Tbilisi, in which 1254 randomly sampled individuals took part. Half of the respondents were asked to imagine that their preferred party had won the next parliamentary elections while the other half were asked to imagine their preferred party had lost.

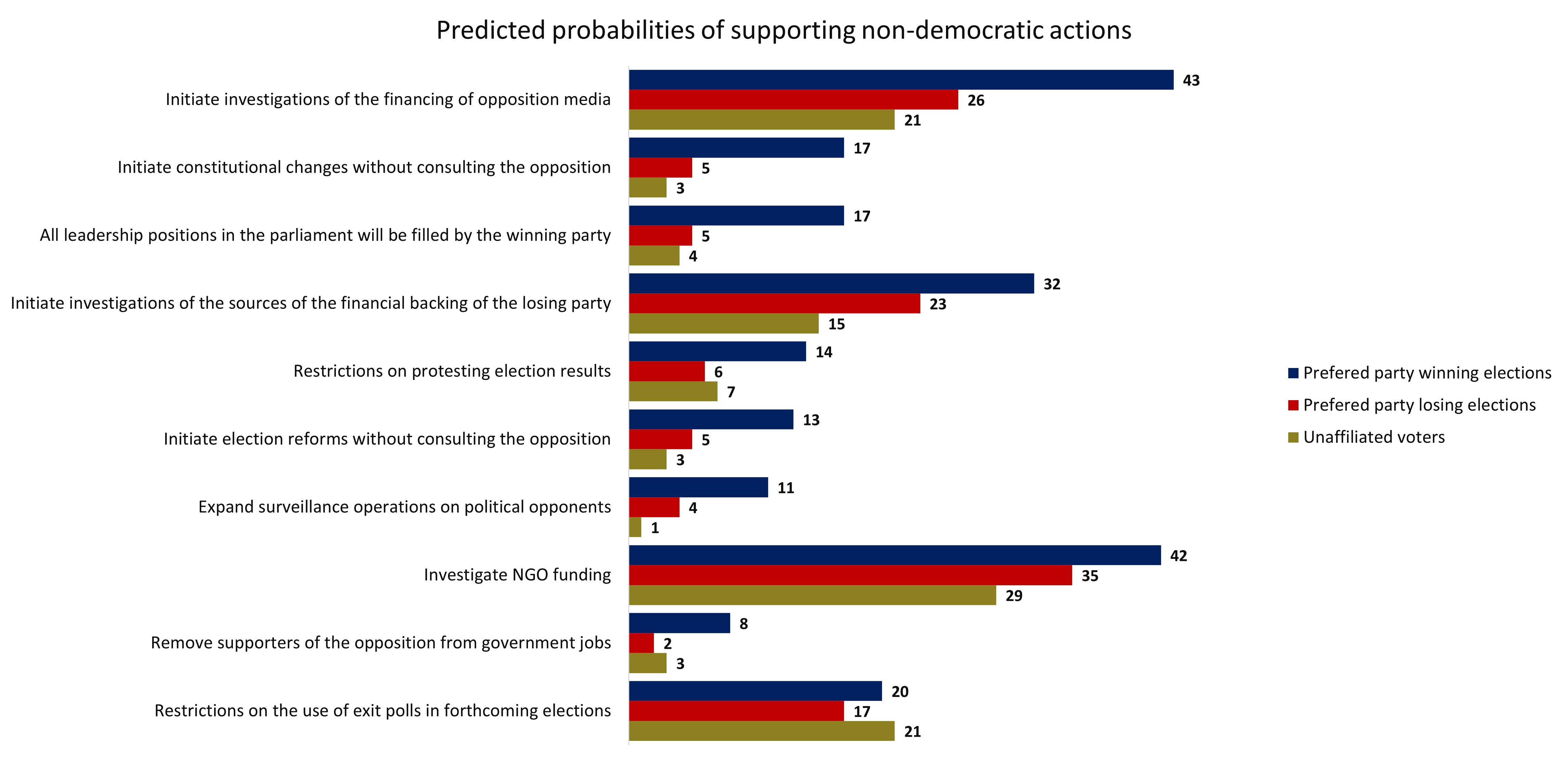

Afterwards, respondents were asked whether they would support ten different policies, as shown in the chart below.

Support for each policy varied from 30% (investigation of NGO funding) to 4% (removing supporters of the losing party from government jobs). Support for most policies was low overall, with investigation of NGO funding (30%), initiating investigations of opposition media (25%), investigating the financial backing of the losing party (20%), and restricting the use of election polls (17%) the most supported.

Other policies such as putting restrictions on protesting election results, giving all leadership positions in parliament to the winning party, initiating constitutional changes without consulting the losing party, initiating electoral reforms without consulting the new opposition, and expanding surveillance operations against political opponents were supported by less than 10% of the Tbilisi public.

However, views on the above propositions varied significantly based on whether or not respondents imagined that their preferred party had won the election.

The share supporting initiating investigations of the financing of opposition media increased by 12 percentage points if they imagined that their preferred party had won compared to when their preferred party had lost the election.

Support for excluding opposition supporters from leadership positions in parliament and initiating electoral reform without consulting the opposition both increased by 10 points in response to imagining one’s preferred party had won.

The share supporting initiating constitutional changes without consulting the opposition increased by nine points, and the share supporting investigations of the sources of the losing party’s financial backing increased by eight points in response to imagining that a preferred party had won.

Support for restricting protests of election results doubled in response to imagining a preferred party had won, as did support for expanding surveillance of political opponents.

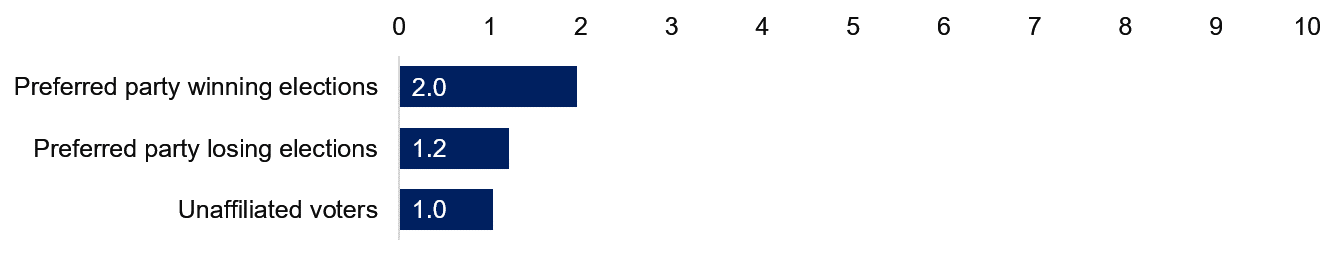

Overall, the data showed that knowing that their preferred political party had won elections increased a person’s tolerance for democracy-eroding policies for one question on average, meaning that the support of voters living in Georgia’s capital for democracy-eroding policies is heavily conditional on the party in power.

The above pattern is not unique to Georgia, and has been similarly documented in established democracies. However, it does call for reflection among partisans in Georgia.

Indeed, an alternative framing of the analysis is that imagining your party has lost elections gives one greater support for democracy. Whether partisans in Georgia are willing to pursue that perspective is, however, another matter.