Friday, November 27, 2015

Awareness of the EU-Georgia Association Agreement in Georgia, one year on

Posted by

CRRC

at

3:11 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Demography, ethnic minorities, European Union, Knowledge

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

2015 EU survey report: Major trends and recommendations

The major findings of the 2015 survey discussed in the report include:

- Support for EU integration is still strong among the population of Georgia, but compared to 2013, the share of those who would vote for EU integration, if a referendum were held tomorrow, dropped from 78% to 61%;

- The fear that the EU will harm Georgian culture and traditions has increased in Georgian society. This fear appears to have contributed to the decrease in the number of supporters of Georgia’s EU membership;

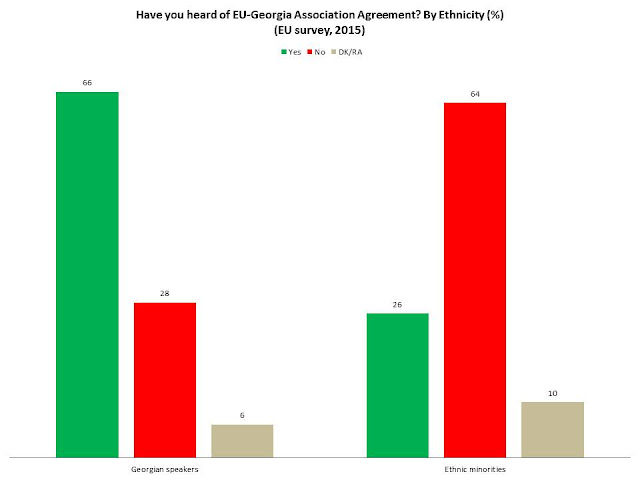

- As was the case in 2013, representatives of the ethnic minority population are the least knowledgeable about the EU and its activities in Georgia, although there is evidence of impressive increases in their knowledge after 2013. Residents of the capital, on the other hand, are the best informed about the EU;

- The population believes that high-ranking Georgian officials benefit more from EU assistance provided to Georgia than regular people do, and knows very little about EU assistance to the general public.

- The Georgian population’s trust towards crucial social and political institutions has been decreasing. The population expresses the least trust in those social institutions, which, potentially, could ensure the democratic development of society – such as NGOs, Parliament, political parties, media and local government.

Based on the most important findings of the survey, EPF has come up with the following recommendations for the Government of Georgia, the EU, nongovernmental organizations operating in Georgia, the mass media, and representatives of academic institutions both in Georgia and EU countries. It is recommended:

- That more attention is paid to the coverage of EU-related issues in the traditional media (first and foremost, on television) rather than the Internet, which is often not available in remote rural settlements. Of course, this does not mean relaxing efforts to spread information via the Internet – online resources should be maintained as an important source of information, but efforts should be enhanced to inform those segments of the population who do not use the Internet. Actors should coordinate efforts to produce more informational and educational TV programs about the EU, its aims and its role. Information should be prepared not only in Georgian, but also in the Azerbaijani and Armenian languages.

- That documents concerning EU assistance spending are made public and accessible, thereby informing society about the diverse profile of its actual beneficiaries. Journalists may produce reports and/or programs recounting the personal stories of ordinary people – farmers, students, nurses, etc. – about the role of EU assistance in their lives. It is important to cover the stories of beneficiaries in various sectors, for example - education, healthcare, civic engagement, the rule of law and the protection of human rights.

- That the reasons behind the fear that the EU is threatening Georgian culture and traditions are thoroughly studied, in order to understand the nature of this fear and the reasons that have contributed to its intensification since 2013. Actors should find ways of relieving or eliminating the fear. Coming to an understanding of what exactly people see as “Georgian traditions”, which of these are being threatened and how, could be a first step in this direction.

- That efforts are enhanced to increase the efficiency of governmental and nongovernmental organizations operating in the country in order to boost the population’s trust in these institutions. One of the first steps in this direction may be a thorough study into the reasons for distrust in the population.

The 2015 EU survey report is available online, here. Over the coming week, we will post a number of blog posts highlighting some of the major findings of the report.

Posted by

CRRC

at

6:26 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Attitudes, European Union, Media, Policy, Trust

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Educated parents, educated children?

Numerous scholars stress that parents’ level of education has a tremendous impact on their children’s educational attainment, as the parents are the first role models and teachers. According to Gratz, children of parents with higher levels of education are more likely to receive tertiary education than people whose parents have lower levels of education. There are a variety of opinions about whether a person’s educational attainment is more closely related to that of his/her father’s or mother’s; still, more and more researchers stress that both parents have an important influence on their child’s education.

This blog post is based on data from the Volunteering and Civic Participation in Georgia survey carried out by CRRC-Georgia in April-May, 2014. The findings allow us to see whether parents’ and their children’s educational attainments are correlated.

The survey provides information on:

- Highest level of education completed by the respondent;

- Highest level of education completed by respondent’s mother;

- Highest level of education completed by respondent’s father;

- Respondent’s self-assessed proficiency in Russian and English languages, and;

- Respondent’s self-assessed proficiency in computer use (Microsoft Office programs, excluding games).

For the analysis performed for this blog post, the data was not weighted.

In line with what earlier studies suggest, Volunteering and Civic Participation in Georgia survey data also show that a person’s mother’s and father’s levels of education are strongly correlated. At the same time, the levels of education of both the mother and father are only moderately correlated with that of the respondent. Still, respondents’ level of education is slightly more strongly correlated with the father’s level of education than the mother’s (see the table below). However, the correlation between the levels of education of the respondent and his/her mother or father weakens when we control for the level of education of another parent.

* The level of education is measured on an ordinal scale with values from 1 to 8 ( 1 – “No primary education,” 2 – “Primary education,” 3 – “Incomplete secondary education,” 4 – “Completed secondary education,” 5 – “Secondary technical education,” 6 – “Incomplete higher education,” 7 – “Completed higher education,” 8 – “PhD, Postdoc or a similar degree”). In order to come up with both parents’ combined level of education, codes for mother’s and father’s levels of education were summed (e.g., mother’s secondary technical education, code 5 and father’s completed secondary education, code 4 would add up to code 9 on the combined scale). This combined scale ranges from 2 to 16; the higher the resulting code, the higher the level of education of both parents taken together, and vice versa.

The chart below shows that when at least one of the parents has tertiary education, the respondent is statistically more likely to also have tertiary education compared to people with parents who do not have tertiary education. This is confirmed by results of a Kruskal-Wallis test.

* The original question on the highest level of education achieved by the respondent has been recoded. Answer options “No primary education”, “Primary education”, “Incomplete secondary education”, and “Completed secondary education” were combined into “Secondary or lower education.” Answer options “Incomplete higher education”, “Completed higher education”, and “PhD, PostDoc or a similar degree” were combined into “Tertiary education”.

** The original variables on the highest level of education achieved by respondent’s mother and father were recoded into the variable “Parents’ education” covering all possible combinations of the parents’ level of education: (1) both parents have tertiary education; (2) both parents have secondary technical or lower education; (3) father has tertiary education, mother has secondary technical or lower education; (4) mother has tertiary education, father has secondary technical or lower education.

As for individuals’ self-assessed proficiency in foreign languages and computer use (Microsoft Office programs, excluding games), more respondents whose parents have tertiary education report an advanced level of knowledge in these areas compared to those whose parents’ level of education is lower. Not surprisingly, the share reporting advanced knowledge of how to use computers is even higher when both parents have tertiary education compared to when only one parent has tertiary education. Interestingly, when only one parent has tertiary education, the level of knowledge of English is reported to be higher when it is the mother who has tertiary education, rather than the father. The Mann-Whitney test shows this difference is statistically significant.

Thus, the data shows that the levels of education of both parents are strongly correlated with each other, while respondent’s level of education is moderately correlated with that of each of his/her parents. The data shows that parents’ levels of education are most strongly correlated to the child’s when the mother’s and father’s levels of education are combined. The respondent’s level of education tends to be higher when at least one of the parents, no matter whether it is the mother or the father, has tertiary education. The same is true about self-reported level of knowledge of foreign languages (English and Russian) and computer use (Microsoft Office programs, excluding games). Those whose mothers have tertiary education report better knowledge of English.

For more information about parents’ level of education and their child’s occupation, take a look at these earlier blog posts: A taxi driver’s tale, Part 1 and Part 2. Also, check out our Online Data Analysis tool.

Posted by

CRRC

at

11:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Education, Georgia, Higher Education

Monday, November 16, 2015

Making energy matters matter: entering the electoral field

[Editor’s note: This is the seventh post in the series Thinking about Think Tanks in the South Caucasus, co-published with On Think Tanks. It was written by Tutana Kvaratskhelia of World Experience for Georgia. The views expressed in this post are the author's alone and do not represent the views of CRRC-Georgia]

Elections are coming in Georgia. Although some thinktankers suggest that elections are a difficult time for think tanks to find an audience, it has also been pointed out that they present opportunities to contribute to the democratic process. At World Experience for Georgia (WEG), in part inspired by previous posts on think tanks and elections at On Think Tanks, we decided to see whether we could indeed help to shape an important debate.

To do so, we developed a set of activities (more on this below) to try to insert energy policy into the pre-electoral debate. Before getting into the details, some background is important.

WEG, Georgian elections and energy policy

WEG is a boutique think tank in Georgia, primarily focusing on the energy sector but also on sustainable development more broadly. Energy issues have strategic importance for the country, but the growing role of foreign interests in Georgia’s energy sector, the lack of transparency in government dealings, and the pre-election populist promises made by politicians, increase the country’s vulnerability to external influences during the election cycle.

In Georgian elections past, political parties have promoted populist, vague and sometimes unrealistic promises that they can rarely keep. While this may not be unusual in some respects, some of the promises have been particularly outlandish when it comes to energy policy. For example, during the 2012 electoral campaign, then candidate and now former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili announced that it was possible to instantly slash electricity bills in half, using Georgia’s sizeable hydroelectric resources. Two months after coming to power, he confessed that the calculations about tariffs were wrong, and he might have overstated what was really possible.

In order to safeguard Georgia’s interests through developing energy security and a European political orientation, WEG has decided to actively participate in pre-election discussions surrounding energy policy in Georgia.

Our proposal: Introducing evidence based policy to the campaign

Electoral campaigns have yet to reach full speed as the elections are still a year away, but to accomplish the above goal, we have started to think about how to make political promises rely on realistic policy options and how we (and think tanks more broadly) can insert our proposals and data into pre-electoral campaigns, leading to impact. As a result, we have developed a strategy for advocating for evidence based energy policy during Georgia’s upcoming electoral campaigns. The strategy consists of three main areas of activity:

- Critical examination of energy issues before the elections – here, we intend to review and analyze the main problems in Georgia’s energy sector. These include the growing influence of other countries in the domestic energy sector, grey areas in legislation and practices, which when coupled with unrealistic populist promises by political parties pose risks to the country’s independence.

- Monitor the party programs during the run up to the elections – this will enable engaged citizens to independently contrast the different policy positions of parties and make an informed choice in the elections. If political parties have not publicly declared their policies, then WEG will contact them directly and request their positions on energy issues. We will analyze their manifestos on a number of relevant indicators.

- Increase public awareness about populist and potentially harmful policies – we are going to communicate with journalists and send them questions to ask while covering the election campaigns. We will also organize roundtable discussions and presentations of our monitoring results during this period.

It is important to note that we are not reinventing the wheel here – reviewing the problems facing a society, monitoring political programs and promises, and public awareness and roundtable events are bread and butter think tank activities. This suggests that if it works, the model will face low adoption costs by other think tanks and provide some organizations which are skeptical of election years as working years a familiar model to work off of.

All the above said, we are still in the process of thinking about and discussing what our options are and how we can improve our strategy. Any additional suggestions or remarks would be highly appreciated. If you have some, please do share them in the comments section below.

Posted by

CRRC

at

6:00 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Elections, Energy, Georgia, Think Tank

Monday, November 09, 2015

Household income and consumption patterns in Georgia

Posted by

CRRC

at

10:52 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economic condition, Economy, Poverty, Purchasing Power, South Caucasus

Monday, November 02, 2015

Nine things politicians should know about Georgian voters

When discussing political competition in Georgia, some politicians bemoan Georgian voters: they describe the majority of voters as socially conservative and economically short-sighted. Therefore, parties have few options to campaign on, beyond promising immediate benefits or subsidies, while keeping silent about liberal values and an open economy.

This blog post shows that despite significant problems related to political competition in the country, the blame directed towards voters is exaggerated. Based on a small scale pilot survey of 342 voters in suburban Tbilisi (representative of the voters living in Gldani and Samgori districts of Tbilisi), and conducted between March and April of 2015, this post shows that voters’ preferences are more nuanced than some politicians give credit for. In fact, voters often hold seemingly conflicting views. Hence, this blog post claims that Georgian political parties have many options to put forward effective electoral programs for the 2016 parliamentary elections.

The questionnaire contained 14 pairs of questions about voters’ preferences on economic and social issues. Most of these pairs of questions included statements with opposed meanings that were read out in a random order. The respondents were asked to agree or disagree with each statement using a scale from 0 (“Completely disagree”) to 10 (“Completely agree”). Hence, the survey helps not only to understand voters’ preferences, but also to examine inconsistencies between the voters’ positions on opposed statements.

Descriptive analysis of the data leads us to observe that Georgian political parties would find helpful. These observations are grouped below under nine major issues, with mean scores for the respective statement, measured on an 11-point scale, reported in parenthesis. All reported differences are significant as tested using t-test. The data was not weighted, hence we use “voters” and “respondents” interchangeably throughout this blog post.

- Economic liberalism: Voters are quite liberal on some economic issues, such as the state’s role in income redistribution and business ownership. For example, more respondents supported the statement that “The Government should provide equal opportunities for economic activity and then should not get involved in income redistribution” (7.85) than the statement that “The government should increase taxes for the rich to finance the poor” (5.33). Moreover, more respondents endorsed business ownership and investments in the country regardless of the investors’ nationality (5.52) compared to reserving business ownership to Georgian nationals alone (4.68).

- Land ownership: Respondents do not mind if foreigners invest in the Georgian economy and own a business, but most believe that the land should be owned by Georgian citizens, no matter how the owner uses it (6.73). The opposing statement – that the owner’s nationality does not matter in so far as s/he uses the land profitably – received relatively low approval (4.37).

- Government spending: As much as respondents appreciate the idea of limited government interference in the economy, they do expect the government to increase social spending, even if this requires cutting money from infrastructure development (6.99). Significantly, fewer respondents supported the option of developing infrastructure even if it requires reduced social spending (3.51).

- Support for democracy: Voters are very liberal in terms of human rights and participatory governance: an overwhelming majority supports the idea that “human rights are a supreme value and should always be protected” (9.19). In contrast, relatively few respondents believe that the state’s interests should prevail over human rights (4.20). Even fewer voters endorse a strong leader who makes decisions for the good of the country (2.99).The vast majority of respondents approve of an elected leader who makes all the important decisions in consultation with the public (7.88).

- Prioritizing traditions: Support for democratic values is not unconditional. If such values clash with traditions, respondents expect the government to sacrifice freedom for the sake of tradition. More voters say that the government should restrict publishing any information which contradicts the traditions of society (6.18), than voters who believe that publishing any information is the publisher’s sole responsibility and the state should not get involved (4.76).

- The split over secularism: It is well known that the Georgian Orthodox Church has been the most respected institution in the country for the past decade. Voters are, however, split on the issue of the church’s involvement in politics: secularists are in the majority (“Religious institutions should not participate in political decision-making” – 5.76). Yet, quite a few respondents believe that, “In policy making, politicians should obey religious institutions” (4.73).

- Law enforcement: Voters support stricter law enforcement than what they witness in today’s Georgia. More respondents report that “The police are too lenient on the people who break the law” (6.05) than agree with the opposing statement (3.64).

- Inconsistent preferences: If voters’ preferences were perfectly consistent, opposed statements would be negatively correlated with a coefficient of -1. However, no pairwise correlation is so strong: the highest correlation coefficients are observed for the land ownership and law enforcement questions (-.56), followed by the questions on religious institutions and business ownership (-.47). It is noteworthy that respondents did not see pairs of statements on the government’s role in income redistribution and freedom of information as having opposed meanings.

- Issues and parties: Increasingly, Georgian voters do not identify with any political party, i.e. they do not name any political party which is “close” to them. It is a very relevant question for all political parties to find out whether such voters are systematically different from their fellow citizens who support a political party. This survey shows that party identification is not a significant factor for issue preferences. Moreover, inconsistency of preferences is also not related to party identification, showing that non-partisan voters are not more confused than partisan voters.

Georgia’s political parties will soon enter a very important race to win votes in the 2016 parliamentary elections. This blog post shows that the window of opportunity for political parties to pursue meaningful electoral programs is quite wide: voters have a range of preferences on significant policy issues such as the state’s role in the economy, human rights, democratic governance, freedom of information, state-religion relations and law enforcement. Surely, a larger, representative sample and deeper analysis is needed to describe Georgian voters in more profundity, but one thing is clear: rational political actors will benefit from systematic and comprehensive study of voter preferences before making judgments about their opportunities and constraints.

Posted by

CRRC

at

11:22 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Georgia, Parties, Policy, Political Parties

Monday, October 26, 2015

Common challenges, common solutions

[Editor's note: This is the sixth in a series of blog posts co-published with On Think Tanks. The views expressed within this blog series are the authors alone and do not represent the views of CRRC-Georgia.]

By Dustin Gilbreath

So far, in this series think tankers working in the South Caucasus have reflected on the issues challenging their countries’ think tank sector. In many ways, some fundamental problems lie at the heart of the specific problems, and I think they can more or less be summed up as problems with language and audience; quality of research; funding; and transparency. This post takes a look at one of these challenges – language and audience – and considers some things that might nudge the region’s think tanks forward.

Language and audience

Language, and specifically the demand for English outputs from donors, limits the size of the audience of research in the region. Zaur Shiriyev has described how the use of English in Azerbaijan in the 90s (and presumably to this day to a large extent) limited the public’s access to research, and Jenny Patruyan reflected on English-centric nature of think tank websites in Armenia. Definitely, different phenomenon, but language is still the underlying problem, and both authors’ issue with language comes from the fact that only an elite or foreign audience can access the research. Notably, funding was cited as one of the reasons for the English language outputs, and donors might help address this problem by requiring publications in both languages (and of course, should also fund translation and/or editing if they do).

When it comes to audience, I don’t think any of the contributors to this series have bemoaned think tanks’ efforts to reach elites so much as highlighted that organizations should consider broadening the reach of their research rather than targeting elites alone. To me at least, expanding to a broader audience seems like a good idea, maybe not for all organizations, but for many. To do this, first everything has to be in an accessible language, but just as importantly it should be in a form that someone will actually consume – only the most dedicated reader will take the time to go through a 50 page policy paper.

This doesn’t mean that we don’t need policy papers anymore, but rather that think tanks here should try to pair their longer, more demanding of the reader outputs with simpler and more accessible ones. Infographics and even products think tanks wouldn’t normally consider producing like games should be options that are on the table. Some progress has been made on the digestibility front, and Jumpstart Georgia’s work provides strong examples for other organizations in the region.

Something that would not only help with the language/audience problem, but also probably contribute to developing quality would be the development of something resembling Think Tank Review. Although the original was spurred on by the need to get policy makers to actually read reports, the organization, in practice, also spreads, archives, and reviews think tank work. For the South Caucasus, there would need to be translation into local languages (and potentially Russian) on top of TTR’s usual work, but language aside, it could improve quality by letting researchers know their work could be reviewed. As internet access is prevalent throughout the region, and most 18-55 year olds here know how to use the internet, something like TTR could bridge the elite to general public gap. Notably, a regional site would help this divided region stay better informed about the goings on of their neighbors, and could serve as a platform for discussing the larger issues facing the South Caucasus as a region rather than as individual countries. Moreover, policy success could be shared and reflected upon.

Of course, these are just a few ideas, which might make dents in the problems described so far in this series. Have other thoughts? Let’s have a conversation in the comments section below.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:34 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Language, Peer-Review, South Caucasus, Think Tank

Monday, October 19, 2015

Do Think Tanks in Georgia Lobby for Foreign Powers?

By Till Bruckner

Most local think tanks in transition or developing countries do not conduct real research. They just act as front groups for foreign lobbying campaigns. Western powers fund them to capture domestic policy formulation processes and distort democracy. Acting in concert with equally remote-controlled, faux-local NGOs and media, think tanks use foreign funds to push foreign agendas, creating a heavily tilted playing field on which the politics and policies favoured by the West always come out top, and on which real democracy can never emerge.

“[T]he project will focus on strategic policy issues identified jointly by USAID and GoG partners… The project will provide support in advancing these issues through Georgia’s policy development and law-making systems and processes. In complementary fashion, support to CSOs and journalists under this project will align with the same set of strategic priorities where possible… Georgian CSOs, particularly think tanks, will receive training on similar skills under the civil society component of this project.”

The views expressed in this blog post are those of the authors' alone and do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC.

Posted by

CRRC

at

6:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Georgia, Lobbying, NGOs, South Caucasus, Think Tank

Monday, October 12, 2015

The development of Azerbaijani think tanks and their role in public policy discourse

[Editor's note: This is the fourth in a series of blog posts co-published with On Think Tanks. The views expressed within this blog series are the authors alone, and do not represent the views of CRRC-Georgia.]

By Zaur Shiriyev

Barriers to development

During the latter years of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijani social science research institutions educated the public and raised awareness about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict with neighboring Armenia as well as national history. They did so by publishing books and making media appearances, which had previously been subject to censorship and/or propaganda under the Soviet regime.

Members of academies and universities played a role in popular uprisings against the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s, and held government positions immediately after independence. However, after a change in government in 1993, most of these people entered opposition politics rather than returning to academia or setting up research institutions that could promote new ideas or policy recommendations for the government.

Without a doubt, research capacity was also weak. Academics were unable to integrate Western social science methodologies into their discourses, and instead, old Marxist dogmas mixed with nationalist rhetoric prevailed. Therefore, despite their early role in public enlightenment, the research institutions did not develop.

Thus, the National Academy of Science – which encompassed over thirty scientific institutions and organizations – remained locked in Soviet tradition, whereby they served the state without any aim of playing a constructive role in stimulating or shaping public discourse. This was the main difference between Azerbaijan and its neighbors, and from the outset weakened the role of research institutions in shaping the political agenda and public opinion.

These two factors – the lack of post-independence capacity building for old research institutions and a political environment that resisted the establishment of Western-style research organizations – were the main barriers to the development of the think tank sector during the first decade of independence. But a number of other factors also contributed.

In the early 1990s, Western funds were used to increase civil society capacity through the creation of NGOs, aimed at supporting democratic development. In pursuit of funding, NGOs called themselves “research institutions” or “think tanks” to increase their chances of securing funds. This led to the creation of increasing numbers of so-called think tanks in Azerbaijan. All that was required by foreign donors from these self-declared think tanks though was official NGO registration status. But, with a tiny number of employees and limited, grant-based funding, these NGOs struggled to fulfill their promises. The pursuit of funding also led to the “one man think tank” phenomenon, and in 2014, there were more than 3000 NGOs in Azerbaijan, and roughly 70-120 of them used ‘think tank’ or ‘research institution’ in their name.

This quasi-think tank community lacked Western-trained academics and experienced scholars, and the standard of work tended to be relatively low. Adding impetus to the problem, rapidly changing donor preferences in regard to subject matter meant that no one had a chance to develop real expertise in any one area (This also took place in Georgia, as observed by Ghia Nodia).

The factors outlined above posed significant institutional challenges, but perhaps even more important was the extent to which think tanks were prevented from participating in public discourse.

Until the end of the 1990s, media censorship limited the public appearances of researchers. Compounding matters, researchers were often working on topics that did not attract public interest. Moreover, funding often came with the stipulation that reports be produced in English, which seriously limited organizations’ audiences to a more educated and informed public.

When experts did appear in the media to discuss political issues, they tended to display partisanship, rather than presenting objective analysis. Weak analytical research skills and the absence of any real policy dialogue with the government undermined this community in the eyes of the public. Clearly, think tanks needed to cooperate and engage with political elites, but the poor relationship between the two sectors prevented this from happening. Moreover, the government did not seek the advice of research institutions, as they lacked the capacity to provide input on, for instance, the development of the economy and energy sectors. Instead, it turned to international expertise. Thus it was international experience that supported the creation of key national institutions like the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan. The government also needed to increase its influence in Western capitals, especially in the US. While policy research institutes could have played a valuable role here, the government, seeking what it saw as an easier and cheaper alternative, invested in lobbyists.

Progress

The development of the expert community’s capacity began in the mid-2000s and stemmed from government initiative and greater human capital. On the governmental side, this process was initiated due to its greater financial resources, its need for institutions to advise it, and the desire to build and integrate a pro-government research community into its overseas lobbying strategy.

In 2007, the establishment of a government funded think tank (the Center for Strategic Studies, or SAM) marked the start of this process. In the same year, Parliament approved the concept of state support to NGOs, establishing the Council on State Support to Non-Governmental Organizations under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The first NGO Support Fund, which gave small research grants to NGOs, required that grant recipients disseminate their research via media appearances. The establishment of the Science Development Foundation in 2009 increased funding opportunities for academic research. In prioritizing research activities, the government sought to improve its national and international image.

The government’s motivation’s aside, there emerged a group of people who had gained experience working at think tanks abroad, primarily in Turkey. Many of them had been educated in prestigious US and European universities. This new human capital dramatically changed things, and the new generation opened up a way to avoid working for government-funded think tanks and research institutions by establishing independent organizations. But the early – unrealized – expectation was that this investment in human capital could lead to the establishment of a think-tank that could offer a model for others in future, as seen in Turkey. For instance, in Turkey, the 2000s saw the establishment of non-state think tanks- a key model in this regard was the Center for Eurasian Strategic Studies, or ASAM (Avrasya Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi); after that other think tanks proliferated based on that example.

In turn, this prompted foreign donors to take a more selective approach to grant allocation. They began to select institutions with the resources and capabilities needed to produce quality research. In 2008, Open Society Institute launched the “Program for Assistance to Analytical Centers”, aimed at improving the quality of political research and ensuring the sustainable development of independent political research institutions. Additionally, increased research funds from the EU within the European Neighborhood Policy framework and requirements for sector-specific research – e.g. on conflict resolution – created a more competitive environment for research institutions, leading to higher quality outputs.

All of the above enabled Azerbaijani think tanks to begin playing a larger role, which is demonstrated by the University of Pennsylvania’s Go-Think tank Report – in 2014, there were fourteen Azerbaijani think tanks listed, up from twelve in 2010.

Challenges

Notwithstanding the positive developments, there is still work to be done.

First, state funded think tanks and research centers have a strong tendency to orient their work towards international audiences, limiting local impact and capacity building, for instance, by improving access to policy research and debate by establishing high-quality policy publications in the Azerbaijani language.

Second, the parameters of enriching public discourse have shifted over the past decade. If in the 1990s, local media appearances were a priority for members of the expert community in stimulating public discourse, today, the combination of a proliferation of poor quality online media outlets together with increased informal state censorship of media has meant that most experts now prefer to publish in international media.

Television remains the main source of news for the majority of the population outside the capital, but expert participation is low. Particularly troublesome is the fact that there are no high-quality analytical programs that could serve as a bridge between the think tank community and the public which would broaden the scope of discourse and debate.

Third, legislative amendments to the Law on NGOs have placed serious limits on foreign funding, and most foreign funded NGOs operating as think tanks – regardless of the quality of their work – are struggling to survive. In general, the successful development of think tanks in international practice has relied heavily on philanthropy, which is absent in Azerbaijan. Thus in the absence of a competitive environment, which is further compounded by the lack of the financial resources, there has been a monopolization of the research market by a few experienced groups.

Conclusion

The development of think tanks in Azerbaijan has faced serious challenges since the 1990s, when Western funding for the development of research centers lacked clear criteria and led the creation of quasi research institutions and one-man think tanks. The distinction between an NGO and think tank remains blurred. In general, think tanks played a minimal role in the shaping of public discussion during the 1990s.

The 2000s saw the creation of some higher capacity think tanks, but as before, the scope of the research was geared towards international audiences rather than the local public. As a consequence, high-quality policy journals and media outlets operating in Azerbaijani never developed. The shift to digital media led to the deterioration of research quality, pushing many professionals to publish in international journals rather than local ones, with the ultimate consequence of limiting the role of think tanks in public discourse.

Overall, the experience of Azerbaijan differs from other post-Soviet countries, especially in the former Eastern Bloc countries, not only because the latter benefited from greater Western investment in institution building, but also because in most of these countries the integration of scientific research into decision-making supported a smooth political process.

Currently, after more than two decades of experience in this field, there are a few main concerns and challenges for the development of the think-tank community that can be identified. The first is financial; without independent financial support, how can non-state think-tanks be developed? Second, given the proliferation of quasi think-tanks, what model for development can be followed, and specifically, can the establishment of research institutions in universities offer a better model for future development? Last but not least, taking into account that the integration of the non-state think-tank community into the policy making process remains impossible, what kind of steps should be taken to improve long term public outreach? One thought is establishing a common online platform for high-quality Azerbaijani language analysis. Have others? Tweet at me here.

Posted by

CRRC

at

6:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Azerbaijan, NGOs, South Caucasus, Think Tank

Monday, October 05, 2015

Think Tanks in Armenia: Who Needs their Thinking?

[Editor's note: This is the third in a series of blog posts co-published with On Think Tanks. The views expressed within this blog series are the authors alone, and do not represent the views of CRRC-Georgia.]

By Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan

Think tanks are considered to be an important part of civil society: providers and keepers of expertise on important social, economic, environmental, political and other issues. Organizations like Chatham House and Carnegie Endowment for International Peace come to mind. In addition to ‘pure’ think tanks, there is a plethora of organizations that combine research with advocacy and action, Transparency International being a prominent example.

What does the think tank landscape look like in Armenia?

First of all, the term itself remains an alien catchword that has not taken root (and, frankly, perhaps it should not). Translated into Armenian (ուղեղաին կենտրոն) it sounds utterly ridiculous. Of the 11 Armenian think tanks mentioned by name in the Global Go Think Tanks Index Report 2014, in fact, only one describes itself as a think tank (in English, but not in Armenian). Some organizations prefer to call themselves research centers: a name that is easily translatable into Armenian. Others have broader descriptions corresponding to their general mandate (“an academic bridge between diaspora [sic] and native Armenian scholars” or a “non-governmental organization … which aims to assist and promote the establishment of a free and democratic society in Armenia”).

Taking a closer look at those 11 organizations (supposedly the top Armenian think tanks as ranked by external reviewers) is an interesting reality check. As the 21st century saying goes: if you are not online, you don’t exist. How do these 11 names fare in a Google search? The table below summarizes the results.

Table 1. Online presence of Armenian entities mentioned by name in the Global Go Think Tanks Index Report 2014

*I did not search for a separate Armenian language web page. Instead, I simply noted if the main English web page has a link to an Armenian version

As a result of my little Googling exercise, one organization (Education and Training Unit) could not be found at all and another two are only mentioned on other organizations’ web sites but have no web sites of their own. Either they were active once upon a time, resulting in their names being listed in some databases, or they are very internet-unfriendly think tanks that prefer not to maintain their own web sites. (Let me clarify that at this point it is not my intention to engage in a discussion on how accurate the Global Go Think Tanks Rankings are, although this small experiment could be a starting point for such a debate. This was simply an empirical approach at trying to gauge the internet visibility of “top” Armenian think tanks). Of the remaining eight organizations, two have not updated their websites since 2013. We are left with only six “finalists” that seem to be up and running. For those studying Armenian civil society this is no surprise. Many organizations in this sector are short lived or exist only on paper.

Who are the main consumers of those research centers’ outputs? Note that two of the six “finalists” (including the research center I work for) have no Armenian websites. This does not mean we do not produce Armenian language reports or policy briefs (we do), but it does tell you something about the main focus. Another interesting little experiment: of these four organizations that maintain both English and Armenian websites, if you just type in the ‘main’ website (like www.acgrc.am for our first example) it will take you to the English version in three cases; only in one case (http://ichd.org/) the first page you land on is the Armenian page. English language seems to be more important. This is no big surprise if you think where the main sources of funding are, but it does raise a question of how relevant think tanks are (and want to be) to the population of their own country.

One might argue that this is not a problem. Think tanks’ main “clients” are decision-makers. In the case of Armenia it should be the Armenian government and the international development organizations. Both turn to think tanks from time to time, but the outputs are produced for internal consumption, making it hard for the think tanks to establish themselves in the public eye, and to improve the quality of their products, as there is no equivalent of peer-review. As a result, Armenian think tanks remain virtually unknown to the public, including such important segments of the public as journalists, students, scholars, and others who would clearly benefit from think tank generated, systematized and stored information.

But is there a public interest in research and analysis produced by think tanks? Here is another little experiment: Civilnet (currently one of the leading sources of online news in Armenia) has about 30 articles in Armenian discussing research conducted by Armenian organizations or individuals: a simple search for the Armenian word հետազոտություն (research) returned 156 hits, out of which approximately every 5th was about research conducted locally. So, yes, there is some interest, and there are news outlets willing to publish think tanks’ stories. Of course researchers have to make an effort to translate their outputs into media- and public-friendly language (and of course, it wouldn’t hurt if it was also translated into Armenian).

While some Armenian think tanks are well established, there are many organizations (claiming to be think tanks) that are short-lived or active only from time to time. Their activity is mostly driven by external funding. They tailor their outputs more towards English readers. As a result, their public outreach and impact remains very low.

This short overview of the Armenian think tank landscape and their visibility online, leads to a number of questions:

1. Does Armenian public need to know more about the think tanks? Should think tanks prioritize public outreach more, or should they use their scarce resources to target donors and top decision-makers?While these questions are beyond the scope of this post and are not likely to have simple answers, they are worth deliberating. What’s your take on these issues? Share your insights by tweeting at us here.

2. Do donors have a responsibility to share think tank outputs with the public in a language accessible to the public?

3. How can we ensure the quality of Armenian language outputs, given that the circle of potential peer-reviewers is so small?

Posted by

CRRC

at

6:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Language, NGOs, South Caucasus, Think Tank

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

The lay of the land: An interview with Hans Gutbrod on think tanks in the South Caucasus

[Editor's note: This is the second in a series of blog posts co-published with On Think Tanks. The views expressed within this blog series are the authors alone, and do not represent the views of CRRC-Georgia.]

Interview by Dustin Gilbreath

Dustin Gilbreath: You recently recently pointed out that think tanks in the South Caucasus have come a long way in recent years, but that they still face challenges on some of the fundamentals – quality of research, policy relevance, funding, and operational acumen. At the national rather than regional level, what are the relative strengths of and challenges before the think tank sector of each country?

Hans Gutbrod: The think tank sector is most relevant in Georgia, since Georgia is a context in which ideas are being worked out, and where there is an interest in policy solutions. Citizens have come to expect that the government delivers. So that, in principle, is a great opportunity for institutions in Georgia.

In Armenia, by contrast, policymaking is fairly closed. There are a few elite pockets of discussion, often involving the Central Bank and some other institutions, but in my view, the space for discussion is narrower. There are some bright spots, such as the Civilitas Foundation and CRRC Armenia. Both of those (and I have worked with both, to be clear) can contribute ideas, but the political system offers fewer access points.

Civilitas Foundation, interestingly, has developed into providing even more content and media, and that is a sensible approach, as it can be hard to transmit messages through traditional media that often has an insufficient institutional and financial basis for quality journalism. CRRC Armenia has been active on issues involving social protection for a long time, and has a good network and contacts in that field. Yet, overall, Armenia is punching way below its weight as a country, with only a limited effort to make it an attractive country to live, work and stay in. This limits the role of any research organization. Perhaps indicative of that situation is that even a Prime Minister whose appointment was greeted with at least some optimism, such as that of ex-Central Bank Director Tigran Sargsyan on balance delivered fairly little. When Prime Ministers can't deliver, there's not that much that think tanks can do.

In Azerbaijan, there isn't any think tank scene to speak of. The government typically has tried to solve any problem by throwing money at it, and by throwing any independent voice into jail. The results are mixed, at best. Yet, ironically, an investment in think tanks might be even more important, just for that reason. Ultimately it's possible, but unlikely, that the regime of Ilham Aliyev will last long. The most remarkable aspect about Ilham Aliyev really is how utterly incompetent his government is. They were handed huge amounts of money, and mostly blew it on themselves and a few prestige objects, instead of actually modernizing the country, its universities, and establishing alternatives to oil and gas. While the regime looks solid now, it has so little management capacity that it could unravel quite quickly in a crisis.

The key question is what alternatives will then be available. Given that there is no opposition to speak of, who can be ready to run things? You need to train people who understand the policy issues so that they can deliver results within the first six months of taking over. If you do that, a post-Aliyev government has a good chance. Conversely, if there is no viable alternative things could turn grim quickly, as Libya illustrates. I know this sounds far out right now, but it's important to hedge against downside risks, and thus policy research would be a good investment.

Coming back to Georgia, policy research organizations haven't really caught up with the new realities. The previous Saakashvili government was brimming with ideas. Some of these ideas were harebrained, but others also proved remarkably successful and even visionary. With the government hatching so many ideas, research organizations often struggled to keep up and had limited opportunities to contribute new suggestions.

This has now changed. Most people agree that the current government is much more receptive to outside input and ideas, partially because they produce fewer of their own. Yet we don't see that much input from research outfits. Many policy research organizations, have settled into a comfortable routine of criticizing the government, along with the society. That's understandable, but there is a missed opportunity of bringing in new ideas. Take one example: when the mayor of Tbilisi promised to plant 1 million trees, this would have offered an extraordinary opportunity. Research organizations could have jumped at this issue, coming up with ideas on how to plant these trees, talking about urban planning, reviving parks, greening the city, bringing in excellent ideas that worked elsewhere. Here and there this may have happened, but I haven't really seen a sophisticated paper by anyone that advanced the discussion.

So what's the biggest missing ingredient, for policy research organizations to succeed? In my view, it's curiosity. I myself have been to many events which are interesting, engaging, and where new ideas are being discussed. It's regrettable that often not a single policy researcher is there, even if the event happens close to their office. Improving ideas doesn't happen in isolation. It's a result of intense discussion. It also often requires sifting through lots of less relevant material. Of course, I understand that all these organizations have many other things to do: other projects, administration, other obligations.

Yet research outfits aspiring to be think tanks do need to ask themselves whether at the end of the day they really are passionate about policy. If you have not read Nudge, what are you doing at the table of a policy discussion? I know this is an extreme view, but I do think it needs to be brought into the discussion.

To be a good lawyer, to be a good practitioner, to be a good policy professional – for all of that you need to keep up with what's happening in the field, you need to connect with the community you work in. I wouldn't want my heart to be operated on by someone who is fumbling along, without having checked in with what's happened in the field in the last 20 years. Why should we demand less from think tanks? In the most extreme case, they're involved in open-heart surgery of entire societies.

Donors, too, should be discriminating in that regard, and hold local research organizations to a much higher bar. Asking for more transparency is just one of those aspects -not sufficient, but certainly necessary. We all need to ask more, to get better results, better policy proposals, and ultimately, better policies.

Ultimately I'm fairly optimistic that this can succeed, though think tanks may be dragged into the future rather than leading into it, and existing institutions may be sidelined. The playing field is now better for those that are agile. Ray Struyk has put forward a great book on how to manage think tanks, and this can help ambitious institutions get it right, if they take the materials seriously.

Another reason, to end on a plug for something that I put together, is that now journalists and ordinary citizens no longer need to take anything on faith. They have access to some of the best think tank research through tools such as www.findpolicy.org. So new ideas may come in, though not necessarily from formalized organizations.

The key challenge for all of us is how to accelerate a better understanding of policy. The best think tanks should be ahead of this process, not behind.

DG: In Azerbaijan, given the recent crackdown and shuttering of organizations which could provide just the training you mentioned, where are there (if there are) opportunities to invest in think tanks either from the side of donors or domestically?

HG: I think in Azerbaijan, the key is to invest in organizations that may work on the outside, that help to clarify what really is going on, that use innovative tools, that collect data that highlights how official data just isn't right. In a way this would be a research outfit that could feed into discussions via social media, a kind of research version of the original version of Radio Free Europe. I know that this is difficult, but you really need to invest into thinking precisely when times are particularly difficult. The case for such external research organizations has also been made by Emin Milli, a dissident who spent significant time in jail for daring to speak up.

DG: You noted here as you have noted elsewhere that donors need to push for higher quality research outputs from local organizations. Do you have any concrete recommendations of how to do so?

Well, there are many measures, and not so many have been tried. I would hope that donors engage substantially with this question. Here are some key measures that come to mind.

- Finance: there should be more core financing to start with. Many research organizations are totally projectized, and this makes it harder for them to invest into quality.

- Nudging: at the point of application, ask about quality assurance mechanisms. Some key questions could include what are you actually doing, with whom, how? Can you put this on to your website, to indicate your commitment to such quality assurance? That would be a good start.

- Checklists: use and encourage the use of checklists. For example, does a policy proposal include a budget? Or is it just a wishlist?

- Comparison: encourage and finance small public reviews and comparisons. For example, does an organization make its old reports accessible, or does it lose all materials when updating a website? Unfortunately the latter still happens way too often, and is a great loss. Many organizations barely think of that, and knowing that you will be reviewed could encourage more attention on that issue.

- Network: create access to constructive external peer review. You could potentially encourage the formation of a network of quality review. This would be an experiment, but if it works it could have a transformative impact.

- Transparency: there are many reasons for transparency, but an additional one is that having full financial information on a grantee website helps donor coordination. Donors should not just be transparent themselves, their quality can also be measured by the transparency of their grantees.

I think there might be many more ideas, and that is why we need a debate on these issues.

DG: Any final thoughts?

HG: Yes. Ultimately, the really interesting things often are outside the disciplinary mainstream. I cannot recommend Ed Catmull’s book Creativity, Inc. highly enough. He describes how Pixar works, and how they consistently managed to turn out successful films. This book holds many lessons for creative organizations, and think tanks should be at least somewhat creative, and in the end also tell a compelling story.

Posted by

CRRC

at

9:45 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, South Caucasus, Think Tank

Monday, September 28, 2015

Thinking about think tanks in the South Caucasus

[Editor's note: This is the first in a series of blog posts co-published with On Think Tanks. The views expressed within this blog series are the authors alone, and do not represent the views of CRRC-Georgia]

By: Dustin Gilbreath

Starting from similarly troubled slates at the turn of independence, the South Caucasus countries – Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia – have diverged over the last 25 years, and the region is an interesting case of divergence despite similarity. While in Azerbaijan the government is squeezing the last bit of free expression from the country, Georgia is having its problems but is by far the freest place in the region. Armenia still has space for engagement, but it is not as open as Georgia.

Perhaps unsurprising, the think tank landscape in the region mirrors the environment in each country. While Georgia enjoys a vibrant think tank sector (despite its shortcomings), Azerbaijan has shuttered many of the independent organizations in recent years which produced policy research just as it shuttered independent media outlets. In Armenia, think tankers have limited channels to reach decision makers or see policy proposals enacted, but there is room to maneuver.

Georgia clearly has the strongest sector of the three countries, and it will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. When it comes to impact, it’s clearly here and policy researchers are taken seriously. Just to provide one recent, rather specific example, the Ministry of Finance felt the need to respond to a series of roughly 300 word blog posts from a Transparency International – Georgia analyst on the miscalculation of the budget deficit (see here, here, and here for the blog posts and see here and here for the responses). While no doubt an important issue, 300 words on a blog caused a course change – the government started calculating the budget deficit the way they were supposed to again. Policy research more generally is taken seriously, and it isn’t uncommon for multiple high level officials to be at presentations and conferences. This stems in part from the relatively open institutional environment, but also from the strength of international organizations here, which amply back local organizations. In the medium term though, this backing is going to be a larger question as the county develops, particularly as it will soon be declared an upper-middle income country.

In stark contrast to Georgia, there is hardly any room for policy entrepreneurship in Azerbaijan. In addition to the widely covered imprisoning of journalists, think tanks and many of the organizations which have supported them have been shuttered in recent years. A Russian style NGO law has kept organizations which had funding from spending it. It’s gotten to the point where at least one organization considered carrying a suitcase of money across the border to keep projects going.

Armenia is something of the middle path in the region. Policy researchers are capable of impact, but the pathways to influence are fewer than in Georgia. Organizations can say what they want, but whether anyone is listening is a question. Informal ties, as in Georgia and elsewhere in the world, play an important role.

Contributors

This series will be composed of the following posts:

The lay of the land: An interview with Hans Gutbrod on think tanks in the South Caucasus Interview by Dustin Gilbreath

This interview will introduce the three South Caucasus countries and the think tank landscape from an insider perspective to the On Think Tanks readership. The interview will look specifically at: 1) how think tanks have developed over time in the region; 2) the different institutional landscapes in each country and opportunities for think tanks given the institutional environment; 3) what are the challenges to be overcome and where will the think tank sector be headed in the region in the coming years.

Think tanks in Armenia: Who needs their thinking? by Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan

Think tanks are considered to be an important part of civil society: providers and keepers of expertise on important social, economic, environmental, political and other issues. Similarly to other Armenian civil society organizations, think tanks are fairly institutionalized, but detached from the public. One might argue that it is not a problem. Their main clients are decision-makers: in the case of Armenia it should be the Armenian government and international development organizations. Both turn to think tanks from time to time, but the outputs produced are for internal consumption, making it very hard for think tanks to a) establish themselves in the public eye and b) to improve their quality, as there is no equivalent of peer-review. As a result, Armenian think tanks remain virtually unknown to the public, including to important segments of the public such as journalists, students, scholars, and others who would clearly benefit from think tank generated, systematized and stored information. They also suffer from the general public’s attitude which is projected onto the entire civil society sector: “the grant eaters - harmless at best, sellouts pursuing someone’s hidden agenda at the worst.”

The role of Azerbaijani think-tanks in public policy discourse by Zaur Shiriyev

The establishment of local think-tanks in Azerbaijan was a phenomenon that began in the mid-2000s. In the decade after independence in 1991, Western-oriented or international NGOs had been effectively the only source of policy analysis in Azerbaijan. However, unlike Western-funded NGOs or national chapters of Western NGOs, local Azerbaijani think-tanks had different goals and modes of operation. In particular, the functions of government-funded or supported think-tanks were essentially limited to promoting the party line and strengthening the government’s international image. This piece will analyze the current role of think-tanks in public discussion in Azerbaijan, including an assessment of their strengths and weaknesses.

There is a growing literature on some donors' use of think tanks as lobbying tools, and the arguably blurred line between think tanks and lobbyists. However, this discussion is largely confined to think tanks in wealthy countries. Using examples from Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, this blog will argue that think tanks frequently function as lobbying tools in less developed countries as well.

Posted by

CRRC

at

10:28 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, South Caucasus, Think Tank

Monday, September 21, 2015

Online data analysis (ODA)

Posted by

CRRC

at

6:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Data, ODA, Online, Online Data Analysis, South Caucasus