Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dr. Tamar Khoshtaria, a Senior Researcher at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of NDI, CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

Data from the European Values Study (EVS) of 2017 suggests that values commonly taught to children in different countries appear to be linked to how satisfied communities are with their lives. CRRC Georgia has compared the results between Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and a handful of European countries.

Most people in the world seek satisfaction with their lives; however, whether one experiences it is a matter of numerous potential factors.

One plausible contributor to life satisfaction could be the values parents or society instil in young people.

Data from the European Values Survey suggest that countries where larger shares of the public are satisfied with their life are more likely to teach their children about tolerance, respect, and independence.

Hard work tends to be associated with lower levels of life satisfaction, a trait commonly reported in the South Caucasus and Russia.

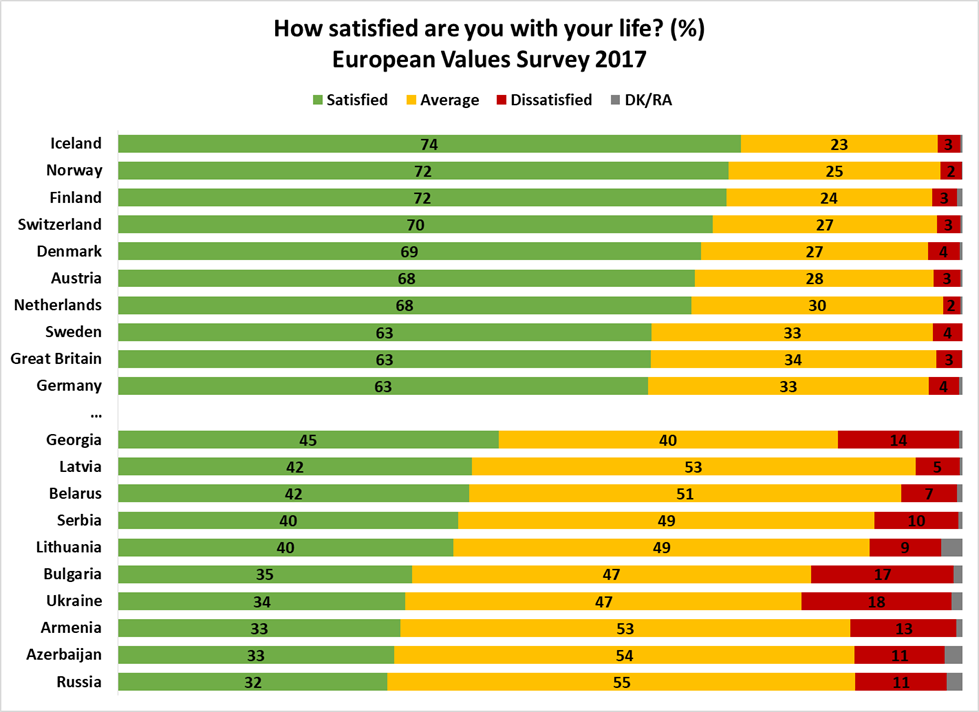

The European Values Survey suggests that Northern European countries reported the highest level of happiness and life satisfaction: data from 2017 suggested that over 90% of respondents living in Iceland (95%), Norway (94%), and Sweden (94%) say they are ‘very’ or ‘quite happy’. In addition, of the 36 countries covered in the survey, Iceland (74%), Norway (72%), and Finland (72%) reported the highest levels of satisfaction with life.

In contrast, only about one-third of people in Armenia (33%), Azerbaijan (33%), and Russia (32%) reported they were satisfied with life. Georgia stands somewhere in between, with 45% of its respondents claiming to be satisfied.

After Ukraine (18%) and Bulgaria (17%), Georgia has the highest share of people who say they are dissatisfied with their lives (14%).

When looking at countries that are most and least satisfied with their lives and comparing them to Georgia, we see that these countries tend to have different ideas on what qualities are the most desirable for their children to learn.

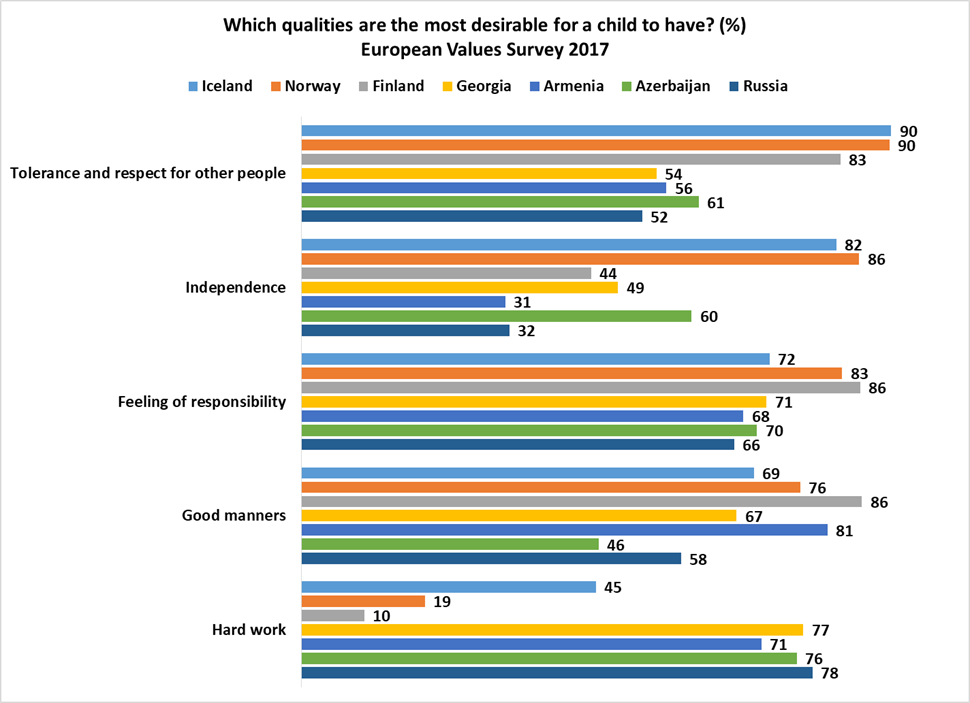

In the countries most satisfied with their lives — Iceland, Norway, and Finland — tolerance and respect for other people were named by over 80% of respondents. This share is significantly lower in Georgia (54%) as well as in the countries where people are least satisfied with their lives — Armenia (56%), Azerbaijan (61%), and Russia (52%).

In Iceland and Norway, though not in Finland, independence is named by over 80% of the public as a highly desirable quality for a child. The share of people naming this quality as most desirable is significantly lower in Azerbaijan (60%) and Georgia (49%) and even lower in Armenia (31%) and Russia (32%).

While over 70% of respondents name hard work as the most desirable quality which a child should have in the South Caucasus and Russia, the percentage is significantly lower in Iceland (45%), Norway (19%), and Finland (10%).

Some qualities were deemed desirable in all seven countries, such as having a sense of responsibility and being well-mannered.

Several patterns also stand out for specific countries. For example, 62% of people in Finland think determination and/or perseverance are desirable qualities, while religious belief is more desirable in Georgia (50%) than in all other countries.

Being able to save money and thrift was valued the most in Russia at 49%. A number of other characteristics show relatively little in terms of distinctive patterns.

The above data show that the most satisfied people in Europe live in Iceland, Norway, and Finland, while the least satisfied live in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia. Georgia stands somewhere in between.

People who are most satisfied with their lives are more likely to teach their children qualities such as tolerance and independence, while the least satisfied communities are more likely to emphasise the importance of hard work.

Responsibility and good manners are generally valued in all of these countries, while religious faith is more important in Georgia than in the other seven countries explored in this article.