Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC-Georgia and OC Media. This article was written by Givi Silagadze, a Researcher at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC Georgia, Caucasian House, or any related entity.

A quantitative analysis of the speeches made by Georgia’s leaders at the annual UN General Assembly found that their themes and priorities changed after the change of government in 2012, with Georgian Dream leaders more positive and discussing Russia less negatively than their predecessors.

The UN General Assembly (UNGA), currently in its 78th session, meets annually in September and offers an opportunity for the heads of state or government of every country to raise the issues that they consider most pressing, as well as addressing an international audience from one of the highest tribunes of the world.

Georgian political leaders have been no exception to this. Examining their speeches from 2007 to 2022 at the UNGA using quantitative text analysis allows patterns associated with the change in government in 2012 to be identified.

Mikheil Saakashvili, the leader of the previous United National Movement (UNM) government, made longer speeches, and spoke more often, more negatively, and more harshly about Russia. In comparison, Georgian Dream’s leaders and President Salome Zurabishvili have been less likely to mention Russia, instead focusing on broader concepts such as development, security, and peace. The data suggests a clear shift in Georgia’s foreign policy discourse.

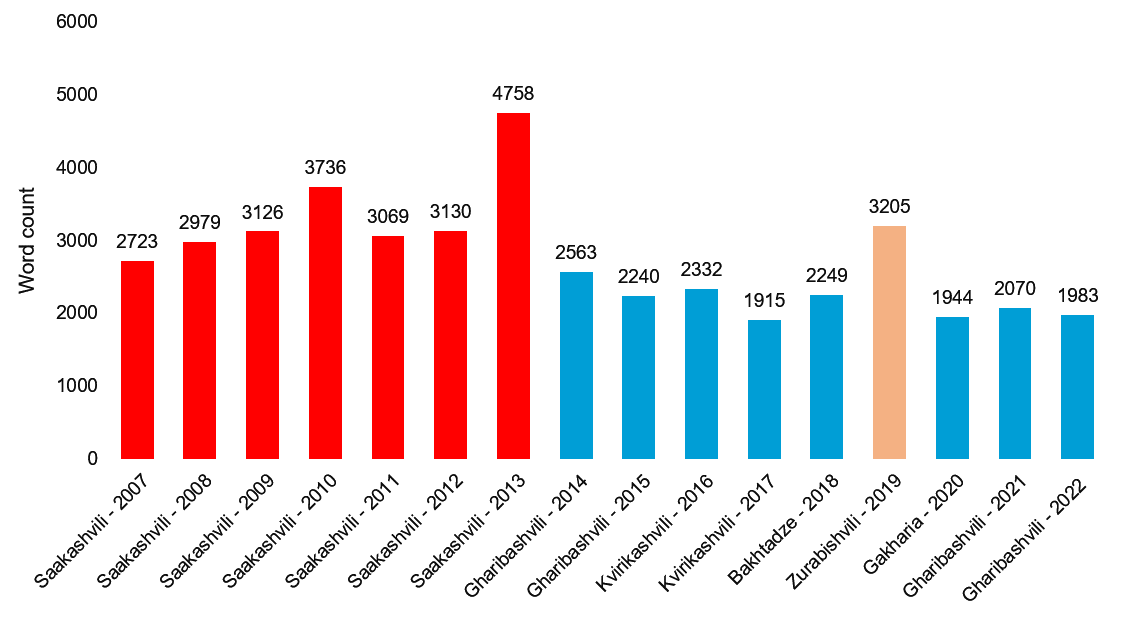

Speech length

Saakashvili made longer speeches than Georgian Dream’s leaders, with his speeches on average containing 3360 words. His 2007 speech was the shortest (2723 words) and his last speech in 2013 the longest (4758 words). In contrast, an average speech after Georgian Dream took over was 2277 words, with Kvirikashvili's 2017 address the shortest (1915 words), and Zurabishvili’s 2019 speech the longest (3205 words).

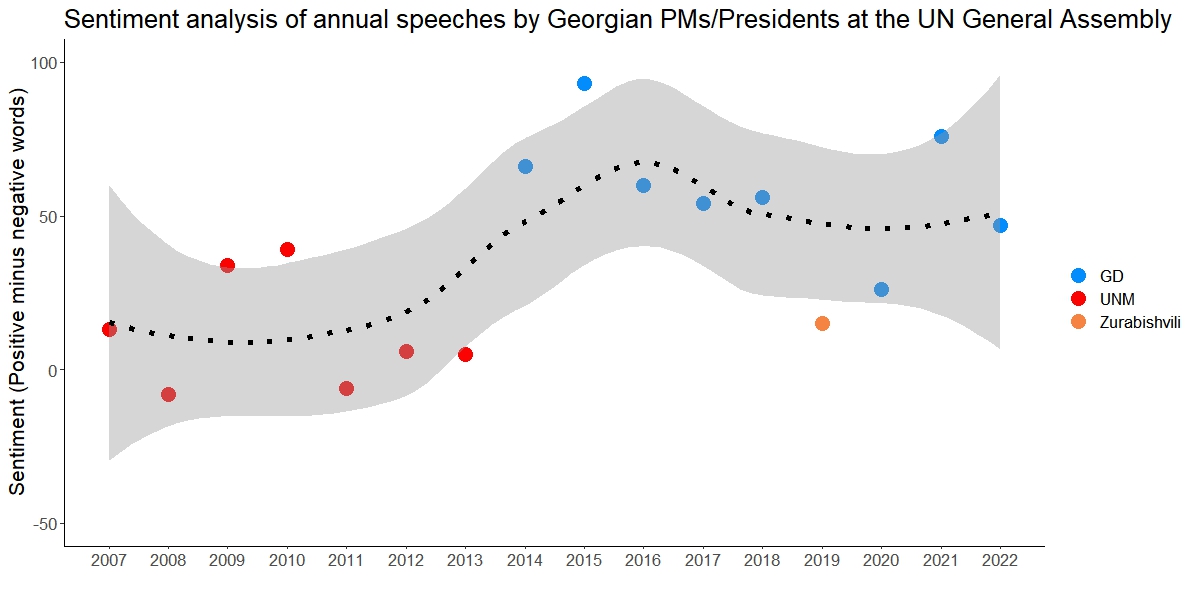

General sentiment

Sentiment analysis of the speeches shows that Saakashvili was generally more negative in his speeches than Georgian Dream’s Prime Ministers. The two speeches with the highest frequency of negative words are Saakashvili’s in 2008 and 2011, while the two most positive speeches are Gharibashvili’s in 2015 and 2021. However, it's important to highlight that Zurabishvili's overall sentiment differs from that of Georgian Dream leaders, with her speech recording a significantly more negative sentiment.

Russia in Georgian leaders’ UNGA speeches

Due to the formal style of speeches at the UN General Assembly, many of the highest frequency words in Saakashvili’s speeches and those of Georgian Dream’s leaders are the same. However, there are some notable differences.

In total, Saakashvili mentioned Russia/Russians 105 times (once in every 224 words) while Georgian Dream leaders did the same 55 times (once in every 373 words). The UNM leader mentioned freedom 51 times (once in every 461 words) while Georgian Dream’s leaders mentioned it 28 times (once in every 732 words).

However, Georgian Dream’s leaders mentioned security 52 times (once in every 394 words), compared to Saakashvili’s 17 (once in every 1384 words). Georgian Dream also mentioned development 92 times (once in every 223 words), while Saakashvili said it 25 times (once in every 941 words). GD mentioned human rights roughly twice as often (once in every 683 words) as Saakashvili (once in every 1568 words), and referred to education 42 times (once in every 488 words) while Saakashvili mentioned it six times (once in every 3920 words).

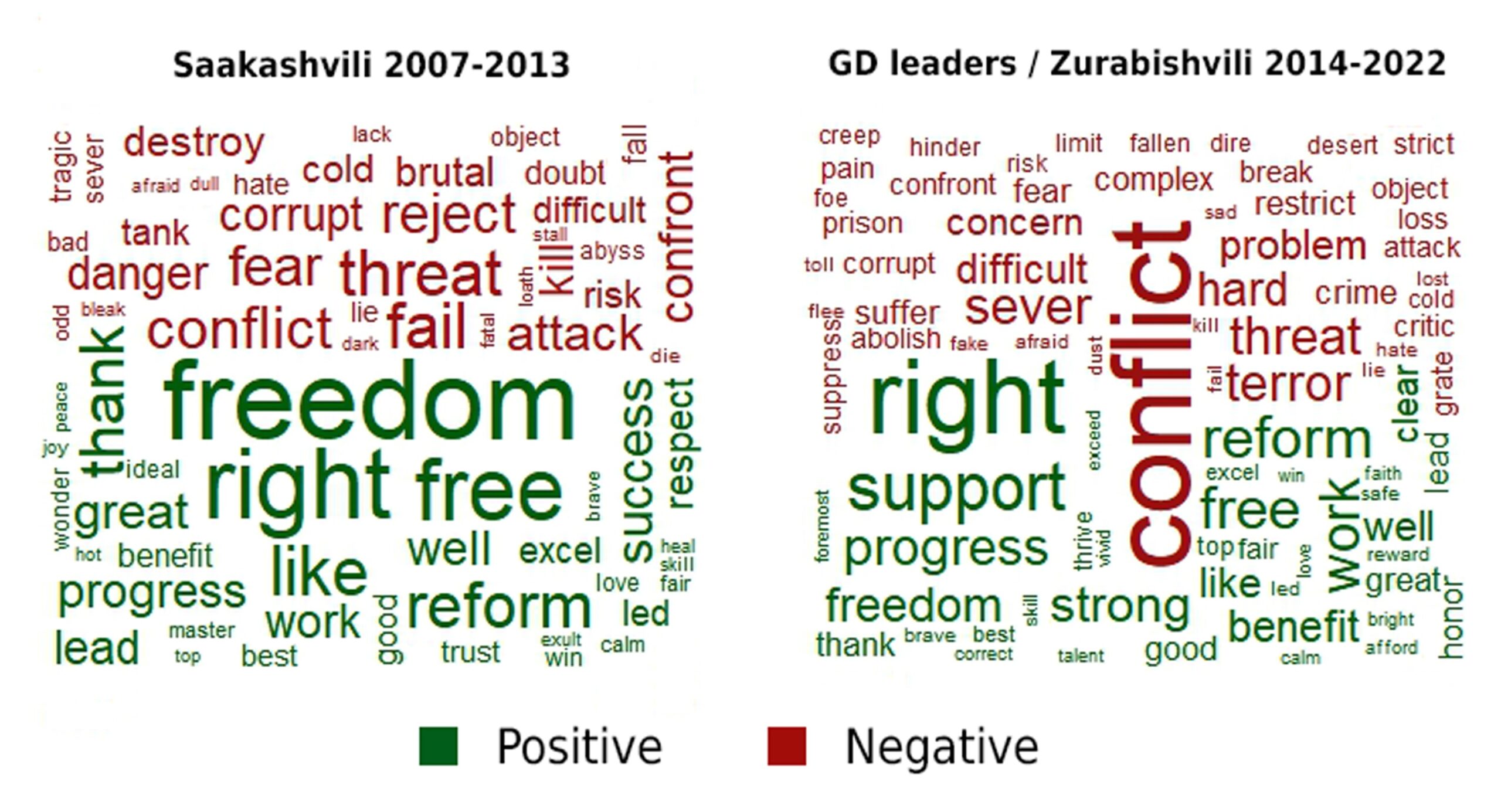

Note: Some of the words in the above word clouds are misspelled. This stems from the analysis method using core parts of words rather than the full word to conduct analysis, a process known as stemming. For instance, the analysis counts peace, peaceful, and peacebuilding in the same manner.

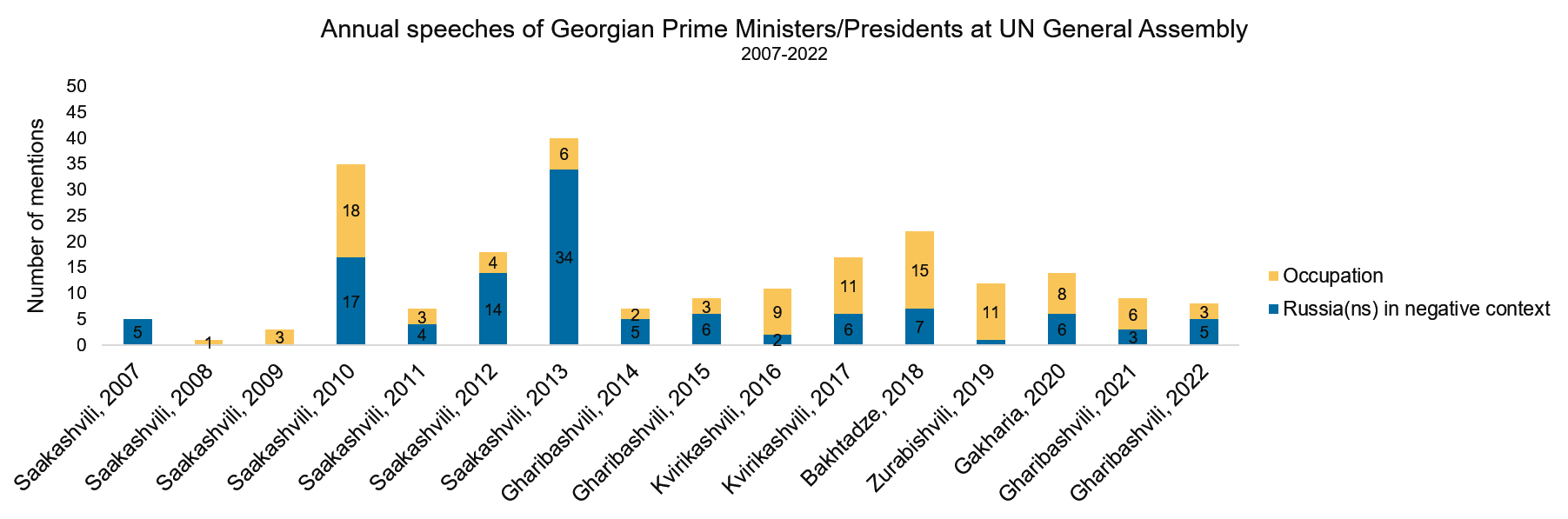

The context of the above mentions is important as well. The following graph demonstrates the number of mentions of ‘Russia’/’Russians’ in a negative context as well as the term ‘occupation’. Saakashvili referred to Russia negatively every 320 words, while GD leaders mentioned Russia in a negative context every 510 words.

Saakashvili’s attitude towards mentioning Russia changed during his time in power. In his speeches just after the 2008 war, he did not explicitly name Russia when speaking about the country in a negative light; for example, in 2008, he stated that ‘Georgia [...] was invaded by our neighbour’. However, in his later speeches, his negative references to Russia were more explicit. In his last speech at the UN General Assembly in 2013, Saakashvili referred to Russia negatively 34 times and mentioned ‘occupation’ six times. By comparison, Georgian Dream’s leaders mentioned Russia negatively only a handful of times in their speeches.

Note: Only direct mentions are counted.

A closer inspection of sentiments suggests that Saakashvili used harsher language when referring to Russian activities in Georgia than Georgian Dream leaders. More specifically, the most frequently mentioned negative terms Saakashvili used were brutal, destroy, danger, tank, attack, fear, kill, and conflict. In contrast, Georgian Dream’s leaders and Zurabishvili’s highest-frequency negative words associated with Russia are conflict, severe, difficult, threat, and hard.

While Georgian Dream’s leaders use the term ‘terror’, it does not refer to Russian occupation.

In terms of positive words, Saakashvili put greater emphasis on the term ‘freedom’, while Georgian Dream leaders prioritised the word ‘success’ more often.

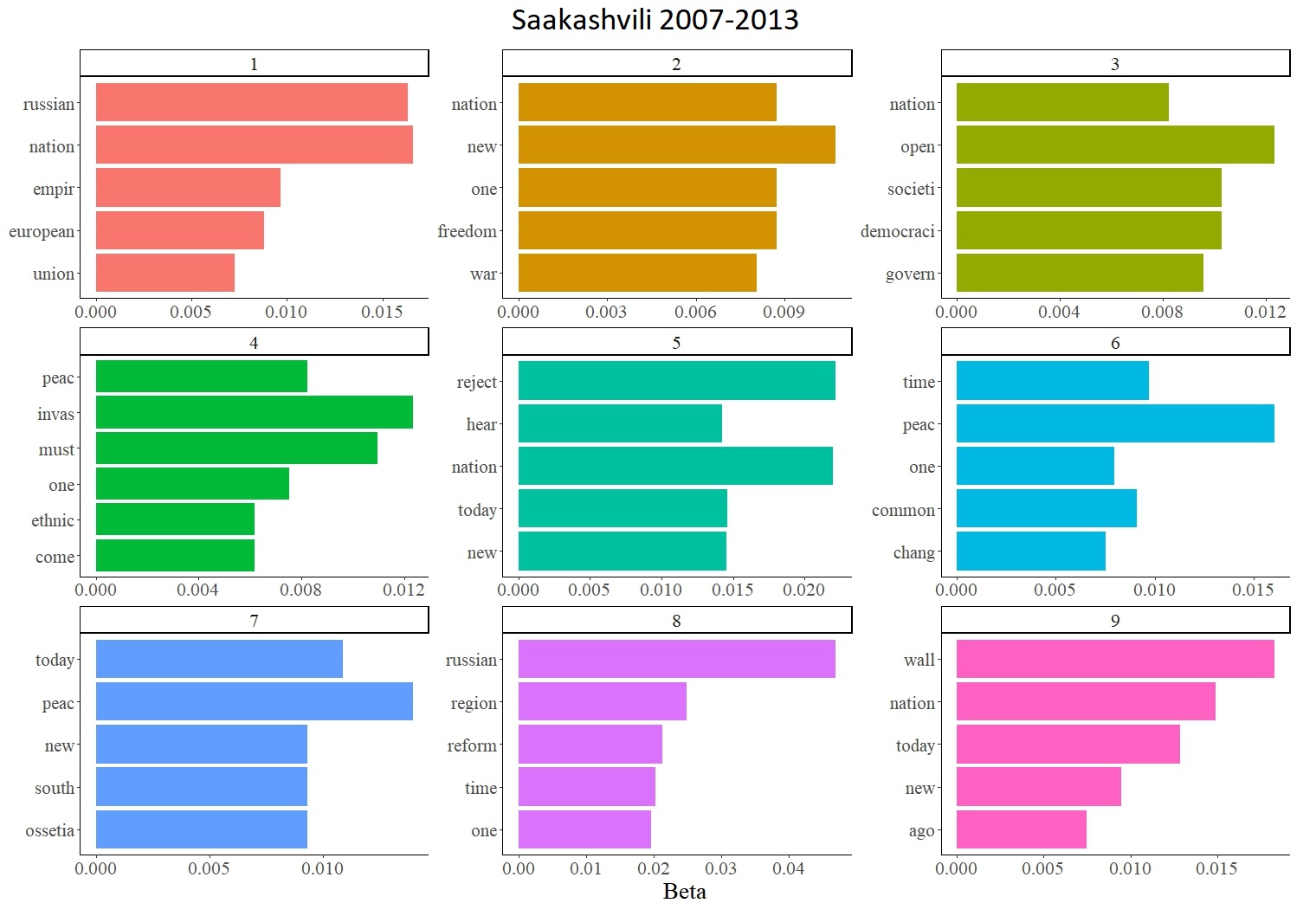

An analysis tool known as topic modeling suggests that the main themes of Saakashvili’s addresses revolve around Russia, the Georgian nation, peace, and democratic governance. Examining the top nine topics suggests there are several recurring terms in Saakashvili’s speeches at the UN General Assembly: Russia (topics 1, 8), war and invasion (topics 2, 4), new and nation (topics 2,5,9), peace (topics 6,7), and democratic governance (topic 3).

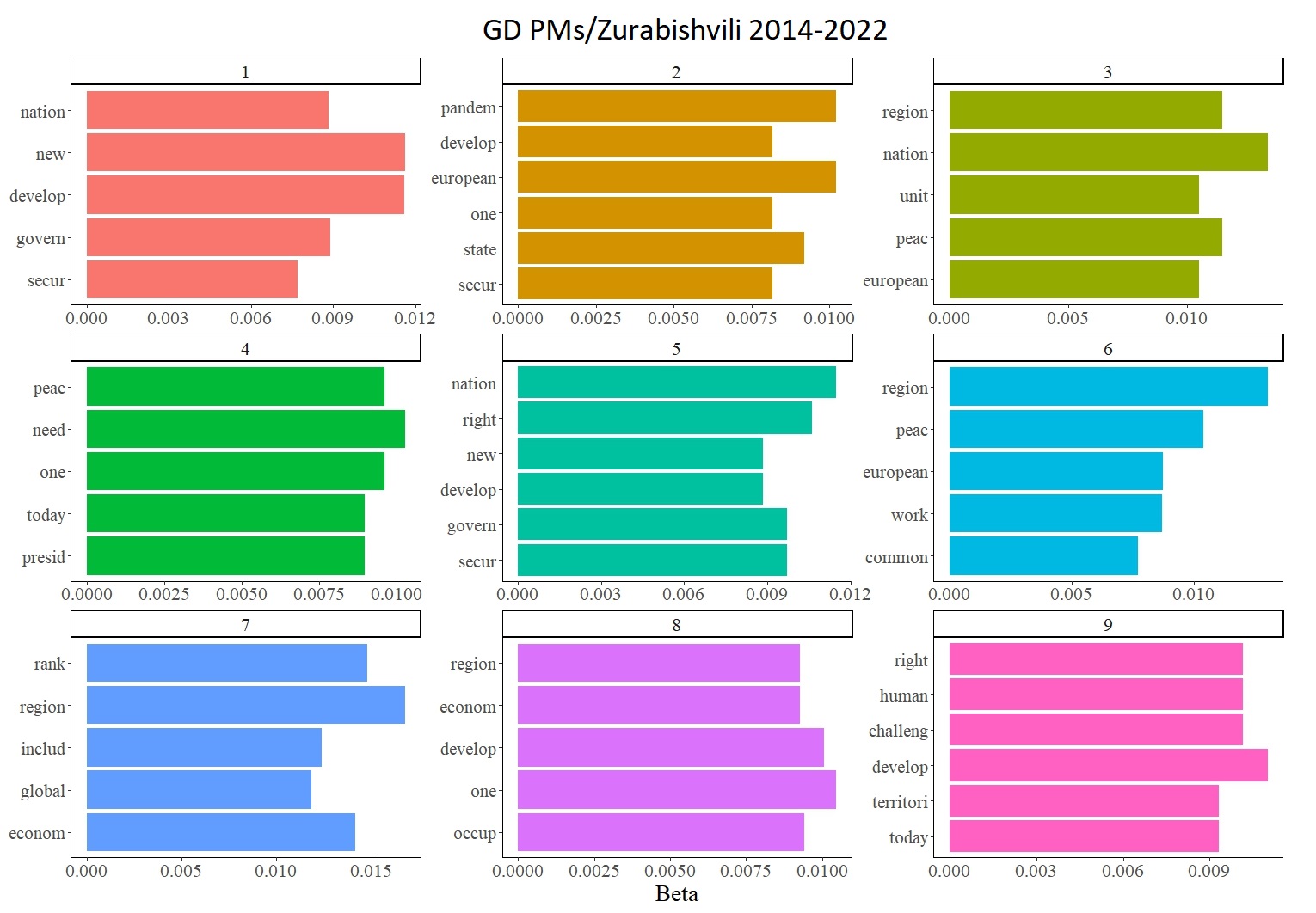

Topic modeling of the Georgian Dream PMs and Zurabishvili’s speeches suggest that their priorities differ from Saakashvili’s. In their top nine topics, none refer explicitly to Russia. Their speeches mostly focused on development (topics 1,2,5,8,9), security (topics 1, 2, 5), peace (topics 3, 4,6), Europe (topics 2,3, 6), rights (5,9), and the economy (7,8). One of the topics (8) does include the term occupation, but mainly in the context of economic development.

The above analysis suggests a shift in foreign policy priorities and Georgia’s international positioning after Georgian Dream came into power. While Saakashvili used harsher and more negative terms, and referred to Russia more regularly, Georgian Dream’s Prime Ministers have been relatively reluctant to refer to Russia explicitly. Instead, they have focused their speeches to the UN on security, development, the economy, and peace.