Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Koba Turmanidze, CRRC-Georgia's President, The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

CRRC Georgia data suggests that about half the Georgian public has a basic understanding of interest and inflation rates.

Saving, spending, borrowing, or investing money are everyday decisions people around the world have to make. Making the right decisions requires a certain degree of financial literacy, which some scholars boil down to understanding the basics of inflation and interest rates.

In a bid to gauge the levels of financial literacy in Georgia, CRRC Georgia used questions developed by professors Annamaria Lusardi and Professor Olivia Mitchell to assess an individual’s understanding of inflation, interest rates, and investment.

Lusardi asked around 16,000 participants in a 15-country study the three questions for a 2019 study, which showed that around one in three people can answer all questions correctly and about a half can understand both inflation and interest rates correctly.

As Caucasus Barometer surveys have shown, people’s lives in Georgia are significantly influenced by inflation and interest rates. While very few people save money in Georgia, people borrow intensively. Notably, since 2015 between one in five and two in five Georgians have named inflation as a top issue in the country.

With this in mind, CRRC Georgia adapted and replicated two of the questions developed by Lusardi and Mitchel — particularly those about inflation and interest rates.

In a January 2022 Omnibus survey, Georgians were asked to imagine that they had an account with $100 in it, and that the account paid a 2% interest rate. They were then asked whether, after five years, there would be more than $102, exactly $102, or less than $102 in their bank accounts.

The second question measured people’s understanding of inflation: again, people were asked to imagine they had a sum of money in their bank account with an interest of 1%, while prices of goods would increase by 2% annually. The respondents were then asked whether they could buy their usual groceries with the same amount of money over time, or if they would pay more or less.

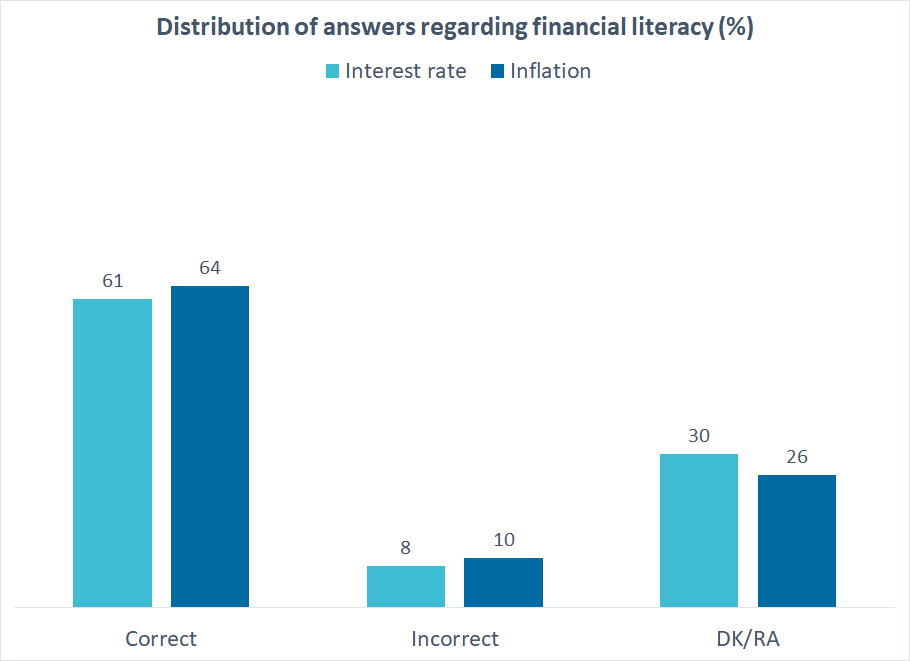

The majority of the public answered each question correctly. Nearly two-thirds (61%) understood interest rates correctly (8% incorrectly, 29% were uncertain, and the remainder refused to answer), and 64% understood inflation correctly (10% incorrectly, 25% were uncertain, and the remaining respondents refused to answer the question). Overall, 51% answered both questions correctly, 26% at least one correctly, and 24% both incorrectly or with uncertainty.

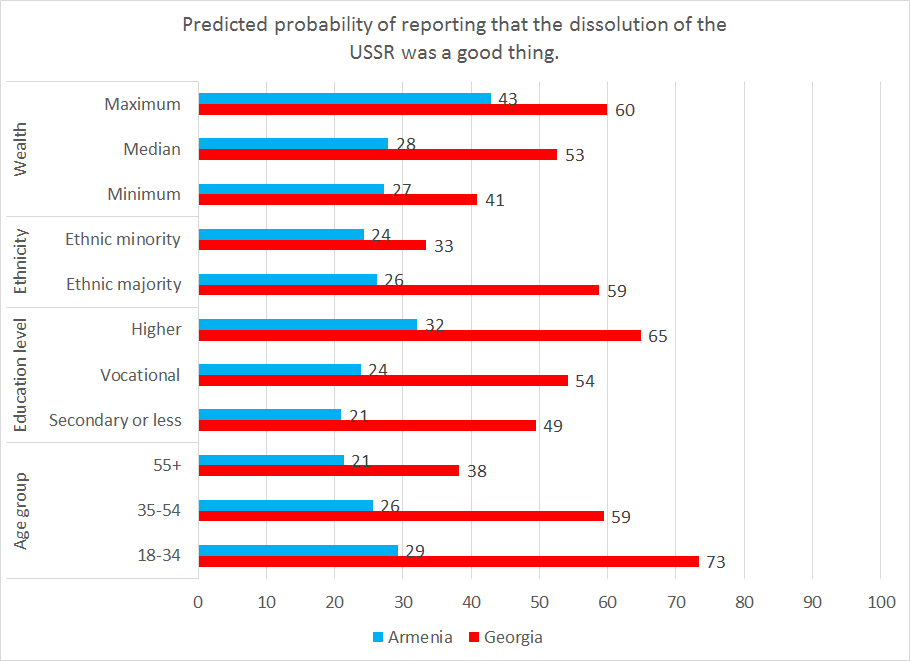

The most important factors associated with financial literacy are education levels and ethnicity.

Individuals who are more educated are more likely to be financially literate: those with technical education 10 percentage points higher, and those with tertiary education 21 percentage points higher than individuals with secondary education or lower.

Ethnic Georgians are 28 percentage points more likely to answer financial literacy questions correctly than ethnic minorities.

Notably, internally displaced persons are less likely to understand inflation rates correctly than non-IDPs, but understand interest rates at similar levels.

Other factors, such as gender, age, having children in a household, employment status, and wealth, are not associated with financial literacy.

When compared with other countries, where similar questions were asked, the results from Georgia show significant similarities and differences. While about 50% can answer both inflation and interest rate questions correctly, just like in other countries, the Georgian data does not confirm gender and age differences documented elsewhere. In contrast, having lower educational attainment and being an ethnic minority is associated with less financial literacy in Georgia.

The data used in this post is available here.