Війна Росії з Україною шокувала світ. Вона також шокувала Грузію, а нове опитування від CRRC Georgia викриває ступінь наявних політичних наслідків.

Наслідки війни, що стосуються зовнішньої та внутрішньої політики Грузії, виявилися доволі масштабними. Офіційна позиція Грузії щодо війни була суперечливою: в той час як прем’єр-міністр Іраклі Гарібашвілі категорично заявив, що Грузія не приєднається до санкцій, накладених Заходом проти Росії, президент Грузії Саломе Зурабішвілі почала медійний та дипломатичний бліц у Європі, висловлюючи рішучу підтримку Україні.

На відміну від реакції влади щодо війни, реакція суспільства була однозначною. Грузини виходять в підтримку України у всіх містах та селах.

З огляду на війну в Україні та навколишні потрясіння в Грузії, 7-10 березня CRRC Georgia провели опитування, яке охопило 1092 респондента. Результати опитування дозволили зробити висновки щодо того, кого грузини звинувачують у війні (Росію), яких дій грузини прагнуть від свого уряду (підтримати Україну), а також щодо внутрішніх політичних наслідків реакції влади (“Грузинська мрія” понесла значні втрати у підтримці виборців).

Грузини звинувачують Росію у війні

Переважна більшість грузинського суспільства покладає відповідальність за війну на Росію (43%) або на Володимира Путіна (37%). Інакше вважають 3% респондентів за винятком 9%, які не визначилися.

Громадськість також запитали про мотивацію Росії до війни. Отримані дані показали, що більшість вважає, що Росія почала війну аби захопити певні території (34%) чи Україну загалом (25%), щоб відновити Радянський Союз (20%), а також щоб запобігти вступу України в НАТО (17%). Інакше відповіли менш ніж 10% опитаних.

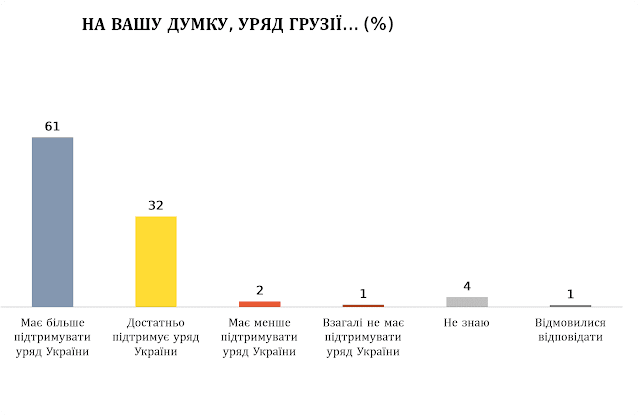

Суспільство хоче, щоб грузинська влада підтримала Україну

Респондентів запитали, чи вважають вони, що уряд Грузії має висловити більшу підтримку уряду України, має залишити наявний рівень підтримки, зменшити рівень підтримки чи не підтримувати взагалі. Значна більшість опитаних вважають, що підтримки має бути більше (61%) або що вона має залишатися на наявному рівні (32%). Лише 2% вважають, що підтримки має бути менше, 1% вважають, що її взагалі не має бути.

Окрім зазначеного вище, респондентів запитали, чи були на їхню думку прийнятними чи неприйнятними певні дії уряду у відповідь на кризу.

Переважна більшість грузин підтримує надання гуманітарної допомоги Україні (97%), прийняття українських біженців (96%), а також надання фінансової допомоги Україні.

Дві третини опитаних (66%) підтримують ідею надання дозволу грузинським добровольцям поїхати в Україну; уряд Грузії намагався завадити цьому.

Близько половини (52%) підтримали б грузинську владу у озброєнні України.

Суспільство хоче, щоб Грузія взяла участь у санкціях

Громадськість бажає, аби санкції проти Росії були сильнішими, а більшість хоче, щоб Грузія приєдналася до них. Це різко контрастує з відмовою прем’єр-міністра Іраклі Гарібашвілі приєднатися до санкцій або впровадити власні.

Опитуваних також запитали, чи вважають вони, що країни, які наклали санкції на Росію, мають посилити їх, утримувати на наявному рівні, зменшити силу санкцій чи не накладати їх на Росію взагалі.

Результати показали, що переважна більшість вважає, що санкції мають бути посилені (71%) або залишитися на наявному рівні (10%). Лише 4% вважає, що санкції мають бути пом’якшені, 3% відсотки вважають, що вони мають бути зняті взагалі.

На питання про те, чи уряд Грузії має приєднатися до санкцій, більшість респондентів відповіли ствердно (66%). Думки розділилися щодо того, чи Грузія має приєднатися до всіх санкцій (39%), чи до деяких (27%). Лише 19% відповіли, що Грузія не має приєднуватися до санкцій взагалі. 14% не були певні у цьому питанні.

Євроатлантичне майбутнє України та Грузії

З огляду на вторгнення Росії, Україна подала заявку до Європейського Союзу, і цей крок швидко наслідували Грузія та Молдова.

Громадськість рішуче підтримує подання заявки Грузією та Україною на статус кандидата в ЄС. В той же час, відзначаються невеликі зміни думок щодо загальної підтримки членства Грузії в ЄС та НАТО (яка вже була високою) з початку війни.

Респондентів запитали, наскільки сильно вони підтримують або не підтримують надання Україні та Грузії членства в Європейському Союзі. Ці дані показали високу підтримку грузинським суспільством надання статусу кандидата до ЄС обидвом країнам.

Респондентів також запитали, чи підтримують вони інтеграцію Грузії в Європейський Союз, НАТО, а також в очолений Росією митний союз.

Дані опитування “Кавказький барометр 2020”, яке включало в себе подібне питання, показали, що 73% грузинів підтримували членство в ЄС, 71% підтримували членство в НАТО. Сьогодні, 75% підтримує членство в ЄС і 70% підтримує членство в НАТО, що статистично не відрізняється від даних за 2020 рік.

Заяви президента та прем’єр-міністра щодо війни

Прем’єр-міністр Грузії Іраклі Гарібашвілі зазнав значної критики щодо своєї реакції на війну. В той час як більшість світової спільноти запровадила санкції у відношенні до Росії, Гарібашвілі твердо заявив, що Грузія не буде брати участі у санкціях. Президент України Володимир Зеленський опублікував твіт з подякою грузинському народу за підтримку, та в той же час розкритикував грузинську владу за її відсутність.

На противагу заявам прем’єр-міністра, президент Грузії Саломе Зурабішвілі отримала широке схвалення за її реакцію відносно конфлікту. Зурабішвілі висловила рішучу підтримку Україні, а також здійснила дипломатичний та медіа-тур країнами Європи у підтримку України.

Зважаючи на зазначене вище, не дивно, що громадськість підтримує дії президента щодо війни значно більше, ніж дії прем’єр-міністра.

В той час як 64% погоджуються з діями Зурабішвілі відносно війни, лише 41% погодилися з діями Гарібашвілі, що показує розрив у 23%. Окрім цього, 15% не схвалили дії Зурабішвілі, а 39% не схвалили дій Гарібашвілі. Таким чином, рейтинг чистого схвалення Зурабішвілі складає +49%, а рейтинг чистого схвалення Гарібашвілі складає +2%.

Якщо розглядати дані, розбиті за партійними уподобаннями, вони демонструють, що вищий рівень ефективності Саломе Зурабішвілі порівняно з Гарібашвілі виходить з більшого рівня підтримки з боку опозиції: в той час як 61% опозиції підтримують дії та реакції Зурабішвілі відносно війни, лише 32% підтримали дії Гарібашвілі. На противагу, Гарібашвілі та Зурабішвілі мають доволі подібний рівень підтримки серед прихильників “Грузинської мрії”.

Політичні наслідки

З огляду на непопулярну реакцію Гарібашвілі щодо війни, не дивно, що підтримка “Грузинської мрії” скоротилася.

Щоб визначити політичні преференції респондентів, в ході опитування ставили такі питання: а) за кого вони б голосували, якщо б парламентські вибори проводилися завтра. Якщо респондент не був певний у своїх симпатіях, пропонувалося відповісти, якій з партій вони віддають перевагу.

Дані демонструють зниження у 10% в підтримці “Грузинської мрії”. Сьогодні, 22% респондентів підтримали б “Грузинську мрію” на виборах, якщо вони проходили б завтра. Для порівняння, у опитуванні в січні 2022 32% респондентів відповіли на це питання на користь влади.

Таким чином, “Грузинська мрія”, хоча б тимчасово, втратила близько третини своїх виборців.

Однак, незрозуміло, чи ця втрата буде перманентною. Дані не показують зростання підтримки опозиції порівняно до даних за січень. Радше, серед громадськості зросли показники невизначеності щодо того, кого б вони підтримали.

Опитування CRRC Omnibus у січні 2022 показало, що 27% респондентів відповіли, що вони були непевні щодо того, кого вони б підтримали на парламентських виборах, в той час як у березні в опитуванні, присвяченому Україні, 38% респондентів відповіли так само, що демонструє зростання на 12%.

Дані також демонструють невелике зниження підтримки опозиції: в січні 2022 підтримка опозиції становила 25%, а в березні 2022 вже 20%.

Доля респондентів, що відмовилися відповідати, яку партію вони б підтримали, змінилася в порівнянні двох опитувань в межах похибки (з 17% в січні до 20% в березні).

В той час як офіційна реакція на російську війну була апатичною, громадськість одностайно підтримала Україну та майже будь-які дії у допомогу країні в боротьбі проти Росії. Погляди суспільства на євроатлантичне майбутнє Грузії майже не змінилися. Тим не менш, погляди суспільства на владу змінилися, а “Грузинська мрія” втратила, щонайменше тимчасово, близько третини своїх прихильників.

Автори статті: Дастін Гілбрет, Давид Січінава, Крістіна Вачарадзе, Анано Кіпіані, Ніно Мжаванадзе, Махаре Ачаідзе, співробітники CRRC Georgia.

Переклад статті та матеріалів виконала Олександра Зур’ян - правозахисниця, співробітниця Центру участі та розвитку (Тбілісі).

Погляди, висловлені у статті не обов'язково відповідають поглядам CRRC Georgia або інших пов’язаних організацій.

Дані, на основі яких базується ця стаття, доступні тут.

Ця стаття була вперше опублікована в рубриці Data Blog від CRRC та OC Media.