This article was written by Zachary Fabos, a Researcher at CRRC Georgia. The views presented in the article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.

The UN Women 2024 survey shows that while Georgians strongly support equal access to higher education and equal pay for women and men, many still believe women should prioritize family care over pursuing a career. These attitudes are especially strong among older age groups and men, revealing a gap between support for women’s education and acceptance of their professional participation.

According to UN Women’s 2024 Gender Equality Attitudes Survey in Georgia, men and women in the country have similar levels of educational attainment, with 39% of men and 36% of women reporting to have attained some form of higher education. This reflects public opinion, wherein a large majority (88%) disagrees that it is more important for boys to receive a university education than girls. Furthermore, 83% of the public agrees that it is important for women to have more access to a higher education. Although the public is generally in agreement that girls and boys should have equal access to a university education, this outlook does not extend to women pursuing a career.

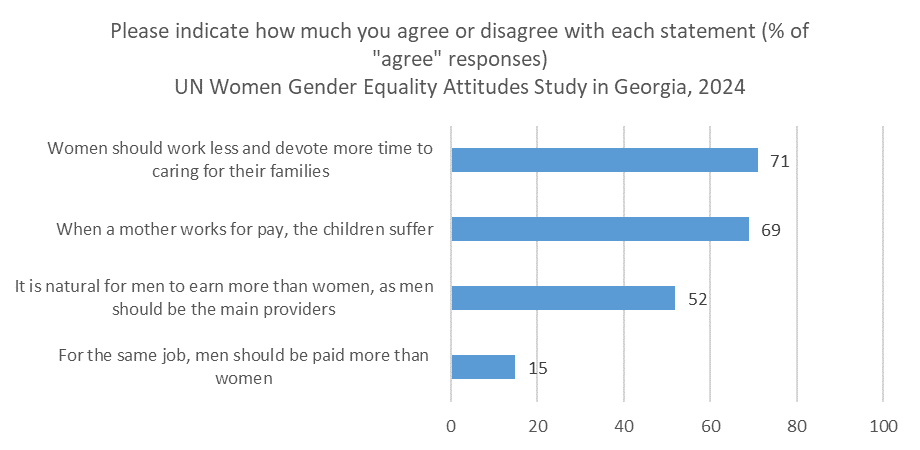

The UN Women survey shows that a majority (71%) of the public believes that women should work less and devote more time to caring for their families. A further 69% believes that when a mother works, their children suffer as a result. A slight majority (52%) believe that it is natural for men to earn more than women, as men should be the main provider in a family. Although preference is given to men as breadwinners in a family, only a minority (15%) agree that men should be paid more than women for the same job.

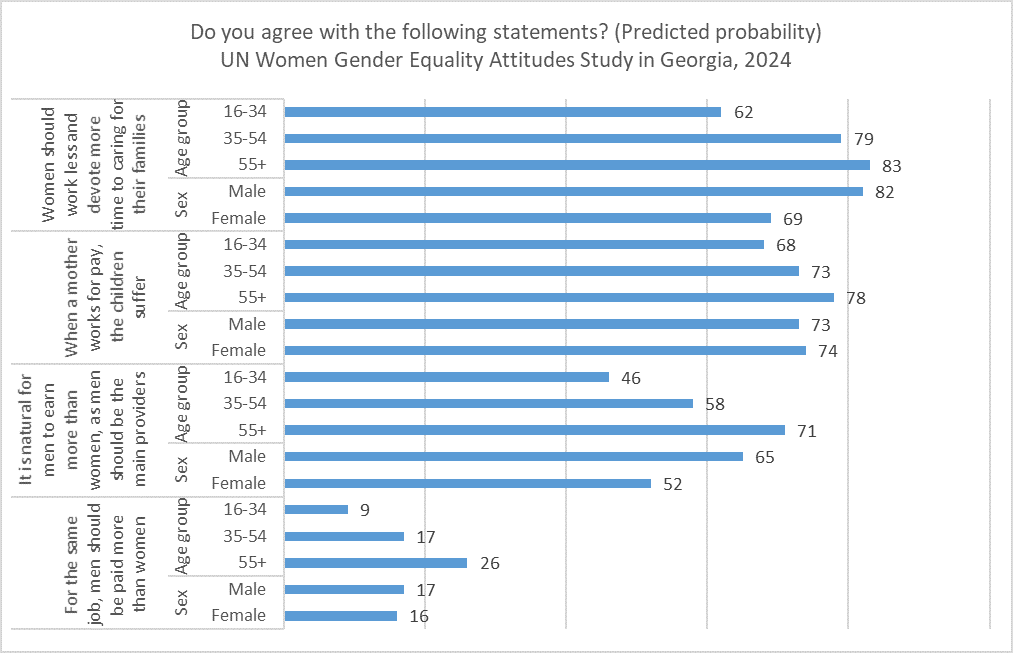

A regression analysis demonstrates that an individual’s age is the strongest predictor of attitudes towards working women. Regarding women’s role in the family, those 55 years of age and older are 24 percentage points more likely than those between the ages of 16-34 to believe women should work less and devote more time to caring for their families. Similarly, 79% of people aged 35-54 agree with the statement.

Despite the public’s high likelihood of having a preference for women to care for the family, rather than pursue a career, a majority (84%) disagree that men should be paid more than women for the same job. However, those 55+ are 17 points more likely than the youngest age group to agree that men should be paid more.

All age groups are likely to agree that children suffer when their mothers work, however older people are more likely to. A person in the oldest age group has a 78% chance of agreeing and a person in the 35-54-year-old age range has a 73% chance. This compares to a significantly lower degree of agreement among 16-34 year olds at 68%. The belief that it is natural for men to earn more than women also varies with age, with 66% of those 55+, 55% of those 35-54, and 43% of those 18-34 agreeing with this statement.

Notably, men and women are just as likely (73 and 74 points respectively) to agree that children suffer when their mother works. On the other hand, men (82 points) are 13 points more likely than women to agree that women should work less and devote more time to caring for their families. By over 13 points, men (65 points) are more likely than women to agree that men are naturally the primary providers for their families and thus should be paid more than women.

Settlement type, ethnicity, education level, and household income do not predict attitudes on these questions, once age and gender have been taken into account.

This analysis demonstrates that regardless of age and sex, Georgians are likely to agree that women should prioritize caring for their family and children rather than pursuing a career. Despite widespread agreement that boys and girls should have equal access to education and receive equal pay for the same job, this sentiment does not extend to women’s professional and career choices after completing said education.

Note: The analysis in this article makes use of binomial regression analysis. The analysis included gender (male, female), age group (16-34, 35-54, and 55+), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), ethnicity (Georgian, ethnic minority), education level (secondary or lower, vocational, and higher education) and reported household income (0-800 GEL, 801-1,600 GEL, 1,601-2,400 GEL, and 2,401+ GEL) as predictor variables.