Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Dustin Gilbreath, a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at CRRC-Georgia, The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC-Georgia, UNDP Georgia, Caritas Czech Republic, Tanadgoma, or The United Nations Development Programme under the Czech-UNDP Partnership for SDGs.

CRRC Georgia data suggests incentivising people to test for HIV and making tests more accessible can encourage more young people to self-test.

HIV and AIDS are highly stigmatised diseases in Georgia: a 2020 report found that half the public would not buy vegetables from someone they knew had HIV, and two in five do not think HIV-positive children should be able to attend school with other children.

This stigma stands in the way of more people being tested for HIV, a critical issue in Georgia.

While the country is on track to meet international standards for the share of HIV-positive people receiving treatment and for those receiving treatment to have viral loads suppressed, only one in three people (36%) with HIV is estimated to be aware of their HIV status.

In this context, CRRC Georgia conducted a study in partnership with Caritas Czech Republic, Tanadgoma, and UNDP in Georgia with the financial support of The United Nations Development Programme under the Czech-UNDP Partnership for SDGs to promote self-testing among young people. The tests were offered by Selftest.ge.

The study found that running a smartphone raffle and minimising the amount of information needed to order a test made young people more willing to participate in HIV self-testing.

The method was found to be comparable in cost to some of the least expensive global interventions used to encourage people to self-test.

To reach these conclusions, the study made use of three randomised control trials (RCT) — the gold standard for scientific evidence. RCTs randomly assign large groups of individuals to receive different interventions. By randomly assigning individuals to receive different interventions, researchers can ascertain that the only difference between the groups on average is that one received the intervention and the other did not.

In total, each randomised control trial had between 38,000 and 54,000 participants, reaching 16-22% of those aged 18–34 using Facebook in Batumi, Kutaisi, and Tbilisi.

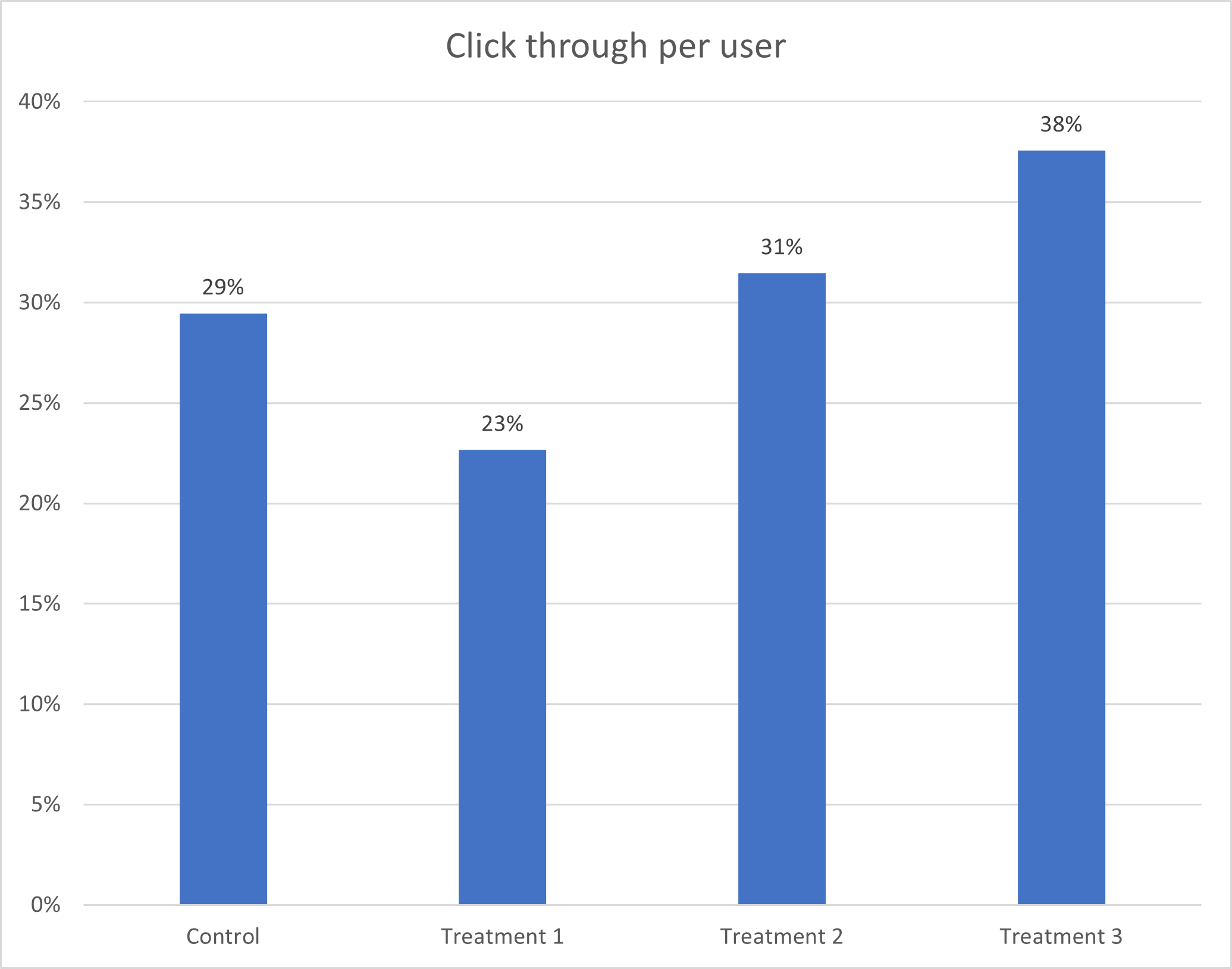

The randomised control trials tested three messages against a basic control message. The first message attempted to assuage people’s fears of being diagnosed with HIV. The second message highlighted that the services of selftest.ge were highly confidential and sensitive to young people’s needs. The third message offered a chance to enter a raffle for an iPhone 13.

The first study found that the iPhone 13 message was more effective than the two others at getting people to click through to the order page, followed by the message which focused on user confidentiality. In contrast to expectations, the message that attempted to assuage young people’s fears about a positive test result had a negative effect — people were less likely to click this message than the neutral control message.

Despite the large scale of clickthrough achieved in the trial, few people ordered self-tests. Project team members suspected that this may have stemmed from individuals not paying full attention to the messages. Therefore, a second trial was conducted with the same messages, but adding a one-sentence highlight of the key message to the Facebook post. However, this failed to produce more orders, with only one HIV self-test order coming through during the second randomised control trial despite thousands of clicks.

In the third and final trial, the study team inferred that the order form was too detailed and complicated for users. A new and simplified order form was trialled on Facebook with the two most effective messages (focusing on anonymity and the iPhone 13 raffle).

This final study started to lead to orders, with the combination of the iPhone 13 raffle and the simplified order form leading to the most self-test orders. In terms of the cost per order, this combination of a simple order form and the iPhone 13 raffle lead to a cost per self-test order of $2.66. This compares favourably to studies conducted internationally, which have identified the cost of testing promotion in the realm of $2 to $50+.

While the stigma associated with HIV and AIDS in Georgia is a large-scale societal problem, enabling young people to access self-testing is critical to ensuring that people living with HIV know that they have it, and in turn, can seek treatment. This study provides one viable path for actors working on the issue to address this challenge.

The full policy brief which this report is based on is available here.

This post was written within the scope of the project Behavioral insights for low uptake of HIV testing in Georgia, which is implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) through the Challenge Fund, with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic.

The content of this material does not necessarily represent the official views of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic, or of the United Nations, including UNDP, or UN Member States.